When MuchMusic first aired in 1984, it was dubbed “Canada’s answer to MTV.” The channel launched the careers of musicians Barenaked Ladies and Bryan Adams as well as media personalities like Nardwuar and George Stroumboulopoulos. Its studio space at 299 Queen Street West in Toronto, once famously open to anyone on the sidewalk, was the nucleus of music in Canada, the home base for original programming like RapCity and the Much Countdown as well as the annual MuchMusic Video Awards.

But that MuchMusic is dead. In 2006, after the channel’s sale to Bell Globemedia (which later became CTVglobemedia and then Bell Media), there were rounds of layoffs and programming changes, pivots and rebrandings. Specialty music channels were cut, as was much of MuchMusic’s original programming. In 2019, music videos were down to just one hour per week. Right now, it’s all reruns: endless episodes of Futurama and Simpsons—which may not have come as a surprise, since the channel eventually dropped “Music” from its name. Its VJs, who were the face of MuchMusic and doubled as hosts, journalists, and entertainers, were all let go. What’s left of MuchMusic’s legacy now lives on in its archive, which is locked away in a Bell Media library and is now being digitized. Access was limited. But former VJ Christopher Ward managed to get his hands on the material and published his oral history of MuchMusic, Is This Live?: Inside the Wild Early Years of MuchMusic, the Nation’s Music Station, in 2016. Material from the archives was also used by Sean Menard for his new documentary, 299 Queen Street West, which premiered at SXSW and will be available on Crave this December.

MuchMusic is often commemorated for its halcyon days, but a proper examination of the decline of media and the dearth of music coverage today can be made by taking a closer look at the outlet’s demise. In other words, the undervaluing of the arts in Canada can be seen through the slow decline of Much. The question isn’t simply “Who killed MuchMusic?” but what confluence of factors prevented it, and other media properties, from adapting. This is especially pertinent because Bell Media, with TikTok, relaunched MuchMusic as a “content-driven digital first network” in 2021 with little fanfare. To better understand why MuchMusic wasn’t able to adapt to shifting tech and viewer habits, I spoke with former and current employees individually (some preferred to stay anonymous). We discussed the channel’s many iterations and what can be learned from each of them.

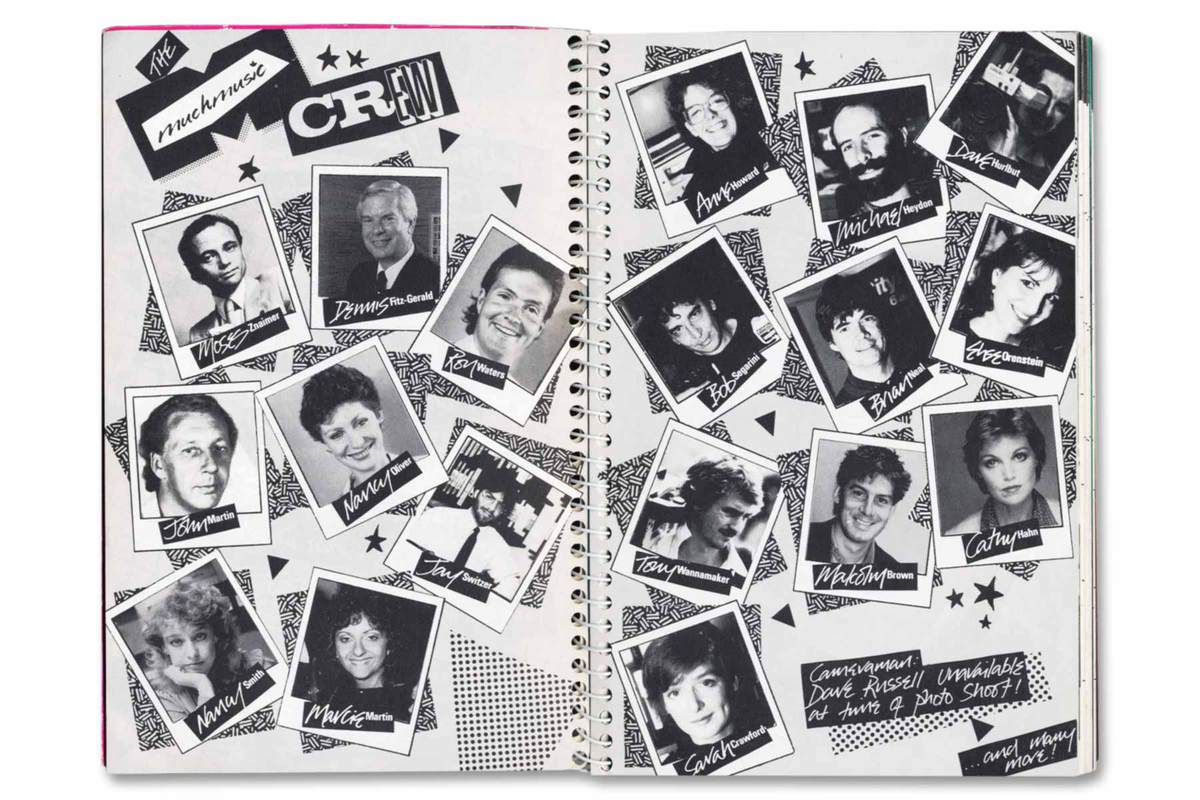

In 1972, Moses Znaimer put Citytv on air. It featured less polished but more specialized programming than that of other broadcasters. It was there that he met and hired producer John Martin, a British expat who was once known as the “father of rock video in Canada.” Martin brought incredible musical knowledge, street smarts, and broadcasting instincts to Citytv, which allowed him to create music-oriented shows like The New Music and then City Limits, the MuchMusic precursor that debuted Mike Myers’s Wayne character that later became Wayne’s World. They both would take their programming quirks and guerilla-style filming from Citytv and set out to create a new music hub.

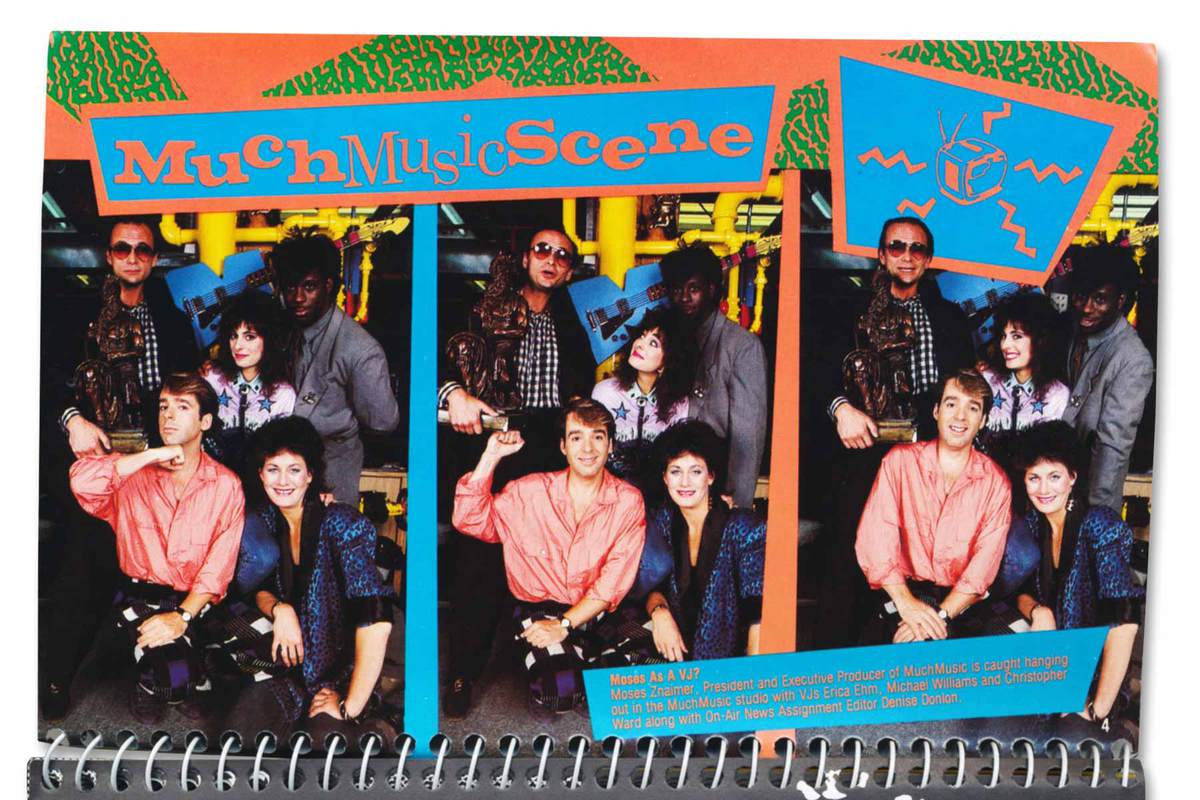

When they launched MuchMusic in 1984, the duo sought to quickly distinguish “the nation’s music station” from MTV, which had begun airing three years earlier. Znaimer explained that rather than bring the camera to the scene, MuchMusic would do the reverse. This approach, which Martin later described as “mould[ing] the anarchy,” altered the relationship between broadcaster and viewer, bringing music to audiences wherever they were. To further cement this relationship, Martin and director of operations Nancy Oliver would create the VJ system. VJs were the direct link between the viewer and the musician. They were like radio DJs—who not only knew their music but looked like the viewer.

At that time, it was all live—no teleprompter, just you and the camera.

Christopher Ward (former MuchMusic VJ): George Harrison came into the studio for a one-hour live interview. When it ended, we stood there in the room, which had been quiet during the interview, but then the regular din returned with a vengeance. And there was George Harrison looking around the room, where people were yelling into phones [because the MuchMusic office was right there], moving cameras, carrying things, and shouting conversations across the room. He looked around and went, “This is a very casual program.” So as I got my moment of understated Beatle wit, I also got an epitaph of MuchMusic, all in one moment.

Michael Heydon (former senior producer, creative services): Moses’s direction and John’s was to just do what you do. Radio had tight programming formats and Moses resisted that, saying that we had to make instinctive decisions and develop our own personality—and that all boiled down to taste.

Michael Williams (former VJ): There’s that Top 40 mantra [in radio]: let’s play only these forty songs until people can sing it and brainwash them with that. We weren’t that. John Martin and Nancy Oliver said: We’ve got tape, cameras, all the airtime you want. Do what you want—we just don’t have any money.

Heydon: There wasn’t going to be any formula. There wasn’t going to be some program manager from CHUM coming down to weekly meetings to advise us on strategy. We wouldn’t be radio. We wouldn’t be MTV.

Bill Bobek (former national publicity manager): At the time, the music industry was very regional, and one thing that MuchMusic did was break all that down. What I mean is that you had stars on the east coast or the west coast that weren’t known in Winnipeg or Toronto. And what really gave strength to the Canadian industry was part of John Martin’s thinking, which was: if nobody knows who k. d. lang is, we can put k. d. lang in rotation next to Bruce Springsteen and Elton John.

It was the best fun you could have with your clothes on and no drugs. You couldn’t break the rules because there were really no rules to break.

Erica Ehm (former VJ): MuchMusic was this great alchemy of music, pushing the envelope and an undercurrent of chaos. That meant that it was a forum for discussion and rich conversation—also that interviews were long, live, and unedited. You never knew where they were going to go next. Our bosses never directed the conversation. When I sat down with a band, no one knew what I would be asking them. No one vetted my questions. It was up to me, for better or for worse. We respected the audience, and the audience respected us back. We respected the artists, and they respected us back.

Sarah Crawford (former publicist for MuchMusic and vice president of social policy and media literacy at CHUM): It was live live. The weird thing about MuchMusic at the time: it was the only place where this would happen. It was quite unusual in that respect.

Ehm: The person that I was off camera is the same person that I was on camera. That was the same for all people they hired in the earlier days. Everybody was hired because they had this burning passion to talk about music.

Ward: We were given phenomenal amounts of freedom by John and Moses. But there was some serious thinking going on behind the veneer of fun and games, and then we were let loose. I dedicated my book to John, “for winding us up and letting go.” And he would: I’d get maybe ten words out of him and then not see him for a week.

Williams: It was the best fun you could have with your clothes on and no drugs. You couldn’t break the rules because there were really no rules to break. There were no impediments because the record companies had no clue: no clue what [music] videos were or what we were doing. They were riding by the seat of their pants and profiting off of everything we did.

Ward: For the first few years, we didn’t have to answer to the sales department. The VJs decided who to play and who got exposure. We were screening videos every single weekend.

Williams: We all were teachers of music for at least three generations of Canadians. MuchMusic also forced CBC Radio and other broadcasters to play music by artists they would never consider. That was important because the country needed to be pushed in a direction that would facilitate success for the local, national, or Canadian artists and give them a platform to go international.

Ward: We were wielding power with a lot of consideration. We were willing to stand by what we believed in and followed that through by continuing to support acts and helping them build long-term careers. An act like Blue Rodeo was floundering until we programmed their first video, “Try.” Other artists told us that as soon as their video aired on MuchMusic, they couldn’t step into a grocery store.

As MuchMusic gained traction and credibility, the working relationship between Martin and Znaimer dissipated, according to Denise Donlon, former director of music programming, in her memoir, Fearless as Possible. Znaimer’s management strategy was always described as “benign neglect,” but he was known for having high standards. Martin, on the other hand, had boundless creativity and resourcefulness but wasn’t, in a corporate sense, reliable. For instance, Ward wrote in his book that before Live Aid aired in July 1985, Ward and Heydon had scored an interview with organizer Bob Geldof. As they wrapped, Geldof asked for Martin’s number so they could talk. Ward and Heydon had to call their boss at his “other office,” a bar across the street.

Znaimer prepared to let Martin go and had already approached Donlon, then New Music host and producer, to be his replacement, according to her. As Donlon explained, it put her in a painful position as it was Martin who had initially hired her. After he gave her his blessing, Martin officially resigned from MuchMusic on December 8, 1992, and Donlon took over as director of music programming.

Donlon summed up her era, in an interview with the Globe and Mail, as a “drive for relevancy.” As she explains in her memoir, pop culture was shaping every aspect of modern life in the early ’90s, and that was reflected in ballooning music video budgets, where big-name directors were commanding seven figures. As more videos hit the airwaves, there was more competition for the spotlight. The commercial success of a song now hinged on the strength of its video because, according to Donlon, “[w]ithout Much and MTV, your success was limited.” If your video wasn’t good, it wasn’t requested at MuchMusic and therefore not played.

The instructions were to make everything look like MTV. We were going away from what everybody adored about MuchMusic and its uniqueness.

At the time, Donlon noticed that the more meaningful aspects of music, like community and connection, were getting lost in all the glitz and glamour. She pushed to unpack videos in more depth and hired VJs with distinctive styles and opinions, like Namugenyi “Nam” Kiwanuka, Sook-Yin Lee, George Stroumboulopoulos, and Rick “The Temp” Campanelli. Defined by her passion for activism, a large part of her mandate prioritized media literacy, with a “Too Much 4 Much” segment where VJs, special guests, and artists analyzed controversial videos that were banned from the airwaves.

Though there was now pressure from sales and marketing to please advertisers and shareholders, Donlon insisted on preserving the quality of program messaging instead of pandering to the lowest common denominator. From 1992 until 2000, she challenged and analyzed the rock and roll lifestyle instead of shilling for it. Under her, MuchMusic simultaneously demystified celebrity and political figures and the making of television.

Dennis Saunders (former MuchMusic technical director): Knowing that Denise was going to be inheriting the mantle [was] comforting [because] she knew us. She was a smart, articulate [person who] shared the same passion for music. She was aware of the game [with advertisers] and far more willing [to] play it. . . . John was detached a little before it happened.

Bobek: John Martin would have verbal battles with the marketing department because they wanted to start playing the Monkees and TV shows like that. That started in ’92 or ’93—you know, around the time of his departure. That shift was happening. It was becoming more corporate, and it was looking at, you know, how can we better sell advertising time?

Donlon: The audience wasn’t coming to us to be preached at. Watching MuchMusic could never feel like they were going to school, but we were hoping to just inject a little spinach every now and then in between all that sugary-candy goodness.

Heydon: We were trying to be aware of what our younger audience cared about, what they were interested in, and what we could offer them that they didn’t know to be interested in. During federal elections, we started bringing in major leaders to spar with Avi Lewis and VJs Jennifer Hollett and Sook-Yin Lee. [Editor’s note: Jennifer Hollett, executive director of The Walrus, was not involved in the commissioning or editing of this story.]

Donlon: Hiring VJs was a part of that: I was not interested in somebody who wanted to be famous. It was really about what would you do with this platform. For young people, we needed feet on the ground and for on-air talent to be interested.

Kiwanuka: The first day I was on camera, I was interviewing the Pet Shop Boys. At that time, it was all live—no teleprompter, just you and the camera. And my first throw: Denise Donlon was standing off to the right with her arms crossed. All these things are happening . . . There was no such thing as “quiet on the set.” It was people doing whatever they’re doing behind you: phones ringing, people knocking at the windows.

Donlon: The audience was used to seeing our mistakes on air. And that was part of the attraction: we had no idea what was going to happen. It was live, with no teleprompters. It’s partly about making sure that you’ve got the right people in place. One thing is you can’t teach curiosity. You can’t learn a sense of fairness and balance, so supporting the people who were there was really key to playing more freely.

Kiwanuka: Eventually, I became used to just having free-flowing information in my head and no teleprompter. Even when we did those hour-and-a-half-long interviews or performances at Much—I would have the information in my head.

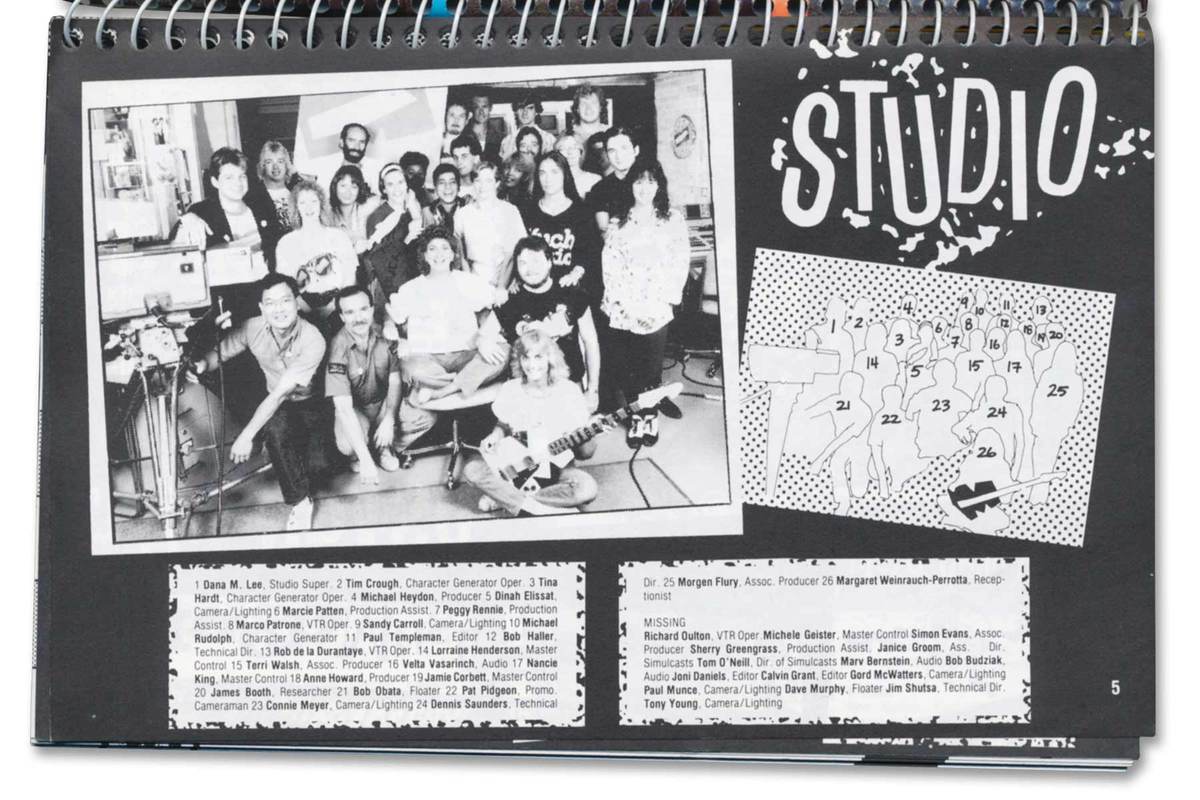

Campanelli: The thing that brought us and the fans together was when they opened the doors of the studio on Queen and John. We were at street level, so we were accessible to people walking down Queen. At MTV, they were on the second floor at Times Square and almost untouchable. At Much, you got a glimpse of what was going on inside, or you could be part of the environment as an audience member. We weren’t really speaking to young Canadians; we were speaking with young Canadians.

David Kines, who was there at the launch of MuchMusic in 1983 and worked there as an editor, became vice president and general manager in 2000. But with the title came the advent of technological change. He and director of music programming Sheila Sullivan would have to devise new methods to compete for the attention of the audience that MuchMusic once commanded.

Napster had been online for a year, and that started to shift the relationship between listeners and their music. Suddenly, if someone wanted to listen to a particular song, they didn’t have to wait to buy it in a record store or hear it on the radio or MuchMusic; they could just download it. With the launches of the iPod and iTunes in 2001 and YouTube in 2005, millennials became the music-on-demand generation. That immediate gratification altered how music was valued, and there was a shift in demand from full albums to singles. It’s worth noting that at its height in 1999, the music industry made $22.7 billion (US) in revenue off of music recordings, according to data from the Recording Industry Association of America.

At the same time, MTV also set out to launch in Canada. In 2001, its CRTC (the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission) licence was approved, though it limited its programming of music videos. As a result, MTV Canada had a lineup peppered with reality shows produced both in Canada and the US. MuchMusic took notice and began a push for reality television programming of its own, including Much in Your Space, Fandemonium, disBand, and MuchMusic VJ Search.

Despite the pressure to emulate MTV, MuchMusic was still governed by strict CRTC guidelines. When the channel launched in 1984, the CanCon requirement was a minimum of 10 percent of all music videos aired, with that number set to increase to 20 percent by its third year of operation and to grow by 5 percent each year thereafter. The channel was now in a bind: it was chasing the audience it once engaged. There was seemingly no plan to get ahead of the audience and the growing importance of the internet. Viewership started to dwindle. Corporate blandification further took over: producers were no longer allowed to experiment. They had to follow scripts, get approvals, and watch MTV for ideas.

Campanelli: With the advent of cellphones and all this stuff, kids were definitely in control of what they wanted. Dave Kines was so technical way back in the day. I remember him holding up a flip phone and telling us [the phone] is going to dictate how TV, as we know it, will be watched.

Craig Halket (former VJ and programmer for MuchMusic): David Kines was nicknamed “Mr. TV.” He is a brilliant broadcaster. He definitely had a passion for music, but he wasn’t connected to the street level. Sheila Sullivan became director of music programming. She came with no actual music programming experience. Her strengths were about being aggressive, not progressive.

Kines: I’m sure people will blame me for MuchMusic being what it was. “Denise Donlon turned it into the cerebral channel, and then Kines just let it become the reality channel with The Osbournes.” You’ve got corporate masters, and anyone that thinks it should still be playing music videos—that’s just not a sustainable business model.

Campanelli: Around that time, I started thinking to myself that I got into this for the music and now these reality shows are popping up. It was becoming less about the music and the bands.

Everyone kept hearing that they were trying to get out of playing music.

Kines: The channel got more focused and scripted because there was more at stake.

Matt Wells (former MuchMusic and MuchMoreMusic host): I remember there were times when I would hear from a producer—who was just relaying information from their bosses—saying, “The ratings aren’t great, and we’re going to have to start playing some more mainstream videos.”

Steve Kerzner (Ed the Sock): In the program director’s office, there was a TV constantly running MTV. And every time you went in there, she’d say, “Why can’t we do shows like that?”

Wells: As you got more ingrained in the company, you understood that if people aren’t watching this show, you need to get eyeballs on it. But there’s got to be a balance between the early days of MuchMusic—where you build, nurture, and let the audience find it—and the accountant or lawyer who says the demographics and statistics tell us that this is what kids will watch.

Kerzner: They lost the plot, tried to copy MTV with a small fraction of the budget and resources, and tried to justify it with “Well, this is popular on MTV, this is what the kids like.” As soon as you start talking like that, you’re separating yourself from your audience in a profound way.

This next part of MuchMusic’s history reflects the history of all media in Canada: consolidation. In 2003, Znaimer left CHUM (amid some speculation that he had been pushed out), the parent company of Citytv and MuchMusic. The following year, CHUM purchased all the MTV Canada channels and then promptly shut them down. Not too long after, it all cumulated with MuchMusic being acquired by Bell Globemedia (later CTVglobemedia and then Bell), a behemoth that controlled some of the biggest media properties in Canada. This would, in many ways, be the beginning of the end for MuchMusic.

Kerzner: The company, all of a sudden, had six vice presidents. And it became much more corporate. Moses started to be seen as a liability because he was mercurial and governed by his passions and inspirations. That didn’t bode well for [corporate] stability.

Heydon: At the very end, CTV [which now owned MuchMusic] started clearing out libraries and rooms in the building. I saw that many of Moses’s mementos had been taken from a fifth-floor library, including master tapes of shows he had developed—historic things that were dear to him. I found awards and framed stills too (including Leonard Cohen’s “I Am a Hotel”)—all of which were destined for the dumpster in the parking lot.

Williams: [CTVglobemedia] buying MuchMusic [and] all the radio stations . . . that’s not good for the country [because] if the government had not given those licences to [them], they would have probably created another two dozen media companies . . . put more money into the system. They also would have created a system that kept local broadcasting going [instead of trying to] program the whole country.

Donlon: After I left, I was invited to be part of the board at CHUM. I was there during the sale. I didn’t physically negotiate it but saw it going down. I was very involved, largely because I was one of the few independent members of the board. In terms of what was about to happen with Much and MTV because of the sale—that meant that suddenly MuchMusic and a number of those specialty channels were now under the same ownership.

Williams: Diversity in media does not exist in terms of media ownership. . . . We had MuchMusic and I don’t think anything’s left now. I went there a couple of times after I left, and it was just a different animal. That’s what happens when you’re bought and sold.

Donlon: From a business point of view, you’re going to have to pare down duplication so that it can work on the ledger side. That’s what I was nervous about: that there was going to be some fallout. I was hoping that the impact on the Canadian cultural industries wasn’t going to be bad.

Heydon: After CTV bought the channel in 2006, they started letting people go. Ivan Fecan, who was president and CEO of Bell Globemedia at the time, met to reassure us. He explained that even though all of the CHUM channels, including MuchMusic, had been bought, it was because Bell Globemedia believed in them—we had built the channels to the point where they were attractive to them, so they were going to let us do what we did. They wanted us to be part of the team and successful together. In practice, that didn’t turn out to be quite true. The truth was that people continued to be laid off every week. Over the next couple of years, hundreds of us became efficiencies. I was one of 105 staff members laid off on November 27, 2008. The entire staff of MuchMoreMusic was gathered and told they were no longer needed. It was very dehumanizing and quite traumatic.

Halket: The instructions were to make everything look like MTV. We were going away from what everybody adored about MuchMusic and its uniqueness—to get in line with MTV. It was a very difficult time at that point. And people were fending for their jobs.

Liana Kerzner (former producer and host at Citytv and CHUM): The chain of command got a little weird—there was a dual management structure, which I think was part of the problem. Nobody could make a decision. You had some excellent content purchasers, but you didn’t have an overarching idea for a channel mandate, and so it splintered and became irrelevant.

In 2008, Brad Schwartz became senior vice president and general manager of the Much MTV Group. In addition to reviving some specialty music shows, including The Wedge (alternative and indie music) and RapCity (hip hop), Schwartz focused MuchMusic’s programming on more youth-oriented drama shows out of America, like Pretty Little Liars and The Secret Life of the American Teenager.

But there was no stability for the workers at MuchMusic. In 2011, Bell acquired CTV and began a new round of layoffs, resulting in a skeletal crew. In 2014 and 2015, many of the staff were let go. MuchMusic died quietly. And despite op-eds complaining about the state of the channel, journalists weren’t really examining the larger implications of buyouts and media consolidation until it was too late.

Schwartz: It became obvious that music videos were just not a linear product anymore: a music video in the credits of Pretty Little Liars was going to get a lot more people watching it than scheduling an hour of music videos. Nobody would watch an hour of videos to catch the video they liked. But a million people watch Pretty Little Liars.

Kines: I don’t know if you can pin the end of MuchMusic on Brad Schwartz, but under his watch, they basically turned it into an MTV channel. It was an inevitable evolution.

Schwartz: We still wanted to be a curator and a guide. And that’s why we aired less music videos in this brand reinvigoration. We rebranded MuchMusic to just Much. And we changed the logo. The old Much logo, as amazing as it was, was not very good when you think about it being on iPads and iPhones. We created something that was much more elegant for a digital business. We took the word “Music” off the logo and started really diving into a lot of scripted youth content. We built a channel where music was more of a brand expression than content experience.

Damian Abraham (former host of The Wedge): There was just so much excitement [and] hope. . . . These two shows were going to come back and save MuchMusic. That was definitely said to me multiple times, like, MuchMusic is back. At the same time, there was definitely those conversations early on, where [we were] looking at the ratings being like, well, this is not working. Some days, towards the end, [we] were on at 6 a.m. on a Sunday with no promotion and somehow we would carry the day and be the most-watched show. Which was not to say we had high ratings. . . . That speaks to where MuchMusic’s ratings were at the time.

Anonymous: I remember starting and was like, this is so cool, music is my job, but immediately it was like, “Get to know Marianas Trench and Hedley.” It was a culture shock for me, but that was the market they were relying on. This is 2009, and they were very focused on tweens and teens. That was the demographic. It was not people my age.

Schwartz: The thing that makes MTV and MuchMusic and anything that targets young people successful is to understand your audience and where trends are going to be ahead of the curve—that’s what advertisers look to us for, that we’re always focused on emergent trends as opposed to residual trends. When you’re just constantly focused on what young people are interested in, then you can create a brand and a content mix that will forge an emotional attachment. We are constantly focused on the future.

Abraham: The thing that was really demoralizing is when we would have [these] moments where [something] would land in our laps and I would bring it to the higher-ups and that would get shot down. We had this big meeting and they’re like, “If we don’t have a show that rates out of the box with no promotion, you’re all gonna lose your jobs.” So I called my friend [who was running] the Vice Toronto office and I [asked] if Vice would ever want to do a show on MuchMusic. This was before Viceland or any of that stuff. So [we] brainstormed a rough idea for a Noisey TV show. . . . I made a meeting to talk to [the Much higher-ups]. And I went into the meeting, and I’m like, “Hey, have you heard about Vice?” and the response was, “Kind of.” And it just went south from there.

Anonymous: When Bell came in, there was just so much red tape. To do anything, everyone needed signatures. Original programming was just filling a quota for CanCon/CRTC regulations. Everyone kept hearing that they were trying to get out of playing music. There was an hour during the day where they played videos and that was only out of necessity, and then the rest of it was at night when nobody was awake.

Schwartz: There were always people ragging and shitting on MuchMusic. Reminiscing backwards makes it easier to shit on something. If MuchMusic and MTV do their job right, then they are like a high school: all they have to do is be important for those four years that you’re going through it. Once you’re out of the demo, you shouldn’t watch it. You shouldn’t like it, because now we’re focused on the kids that are here. If you’re forty years old and still liking Much, then we’ve grown old with our audience instead of staying perpetually young. You shouldn’t be watching MuchMusic anymore. It’s not for you anymore.

Anonymous: I remember when the twenty-fifth or thirtieth anniversary that rolled around and they didn’t celebrate it. And it’s because they didn’t want to appear old. They were trying to market to teenagers, and turning that age made them look old.

Abraham: I think they spent their whole time chasing away their demo. The problem was eventually there’s not a younger demo to [get] because [they’re] not watching TV the same way. As it became a pop station, and you saw the same thing happen with MTV, it was very interesting to watch these two parallel downfalls—just them being completely unable to pivot. I think there was such an arrogance that they would always say they’re the most valuable youth brand in Canada, and after a certain point, it’s like, Yeah, well, to who?

On June 7, 2021, it was announced that Bell Media and TikTok would “team up for the relaunch of MuchMusic,” at least initially by bringing on new VJs and “creators that speak directly to Gen Z and younger Millennials.” Bell Media is also redeveloping 299 Queen Street West. But just up the street, in what used to be a CHUM gift shop, is a small studio space for the new iteration of MuchMusic. A sticker on the window marks it off from the street.

I’m assured by David Krikst (head of MuchMusic) that the relaunch will stay true to the early days of MuchMusic. “Every generation has their own version of MuchMusic,” Krikst tells me, “but I’m really energized by the kids who didn’t know the brand.”

MuchMusic’s downfall occurred in parallel with the decline of music journalism at large in Canada. Venues have been shutting down, newspapers have gutted music coverage, alt weeklies are dying, and music outlets aren’t holding up. The Doug Ford government has also been slowly eroding the Ontario Arts Council by cutting its funding. “I don’t want to be all doom and gloom,” says journalist and former pop culture reporter Hannah Sung, “but I do think there’s a real lack of paid work for journalists to cover music in Canada. When we think about how central music is to our enjoyment of life and the way we connect with other people and our own communities, how few critics there are really blows your mind.”

Bell is still sitting on the channel’s archives that hold the history of broadcasting in Canada and gems like the final interview with Tupac and one of the final interviews with Kurt Cobain. The tapes have not been digitized or even labelled correctly, and after a flood and possible thefts, no one except Bell’s librarian knows what remains. When I first began interviewing former employees of MuchMusic three years ago, many expressed frustration with Bell because they had tried to reach out, offering to digitize and organize the archive, but were met with silence.

That seems to have changed for the upcoming MuchMusic documentary, 299 Queen Street West, which gave director Sean Menard unprecedented access to the archive. The documentary seems to be a passion project (or damage control tactic) for Bell: while the MuchMusic relaunch flails on TikTok, Justin Stockman, vice president of English content development and programming at Bell, is credited as the documentary’s executive producer.

With every celebration of its launch or anniversary, MuchMusic becomes more of a cautionary tale, a reminder of what could have been. As I passed the new MuchMusic space late last year, I saw the new generation of VJs banging on the window, trying to get passersby to stop and talk. They were mostly ignored.