L

Whether written as a family schism, a forced migration, an alienation from one’s ancestral culture, or a psychological departure from reality, each of the celebrated novels delves into disconnection and its discontents. Here, each of the authors share how their respective narratives attempt to remedy that exile.

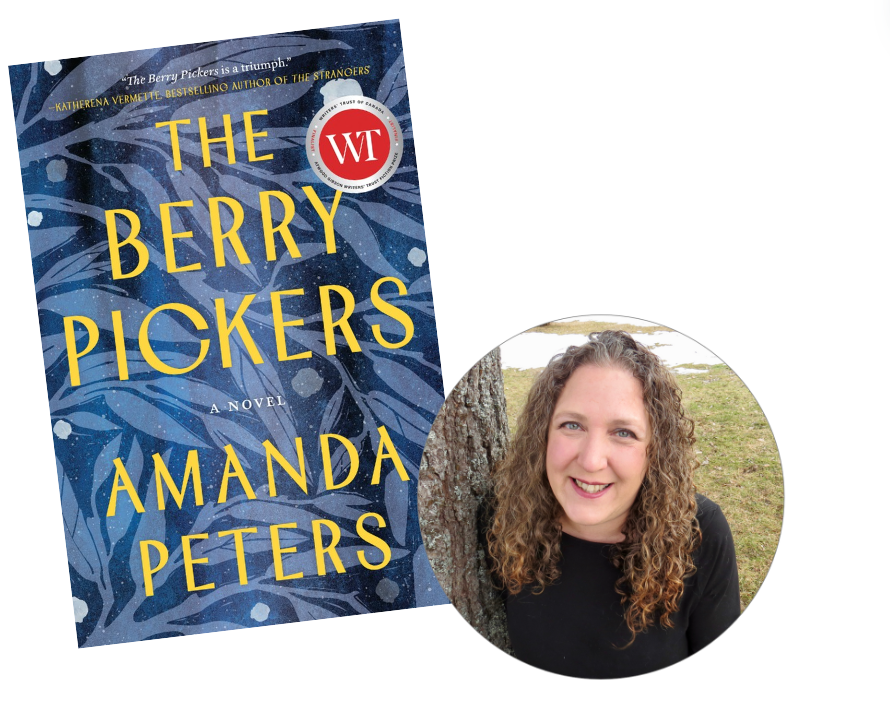

Exile is such a sharp word, almost bladelike. It should be sharp, because it is painful—even if we don’t know we are being exiled. The two characters in The Berry Pickers experience exile; one self-imposed in a misguided attempt to protect those he cares about, and the other because of an unthinkable act. This shapes who they ultimately become. Trauma, grief, violence all derive from their disconnection to their family, their homeland, and who they are as people. But where there is exile, there is always the hope of return. In my book, hope plays a big part and, in the end, it does win.

– Amanda Peters, The Berry Pickers.

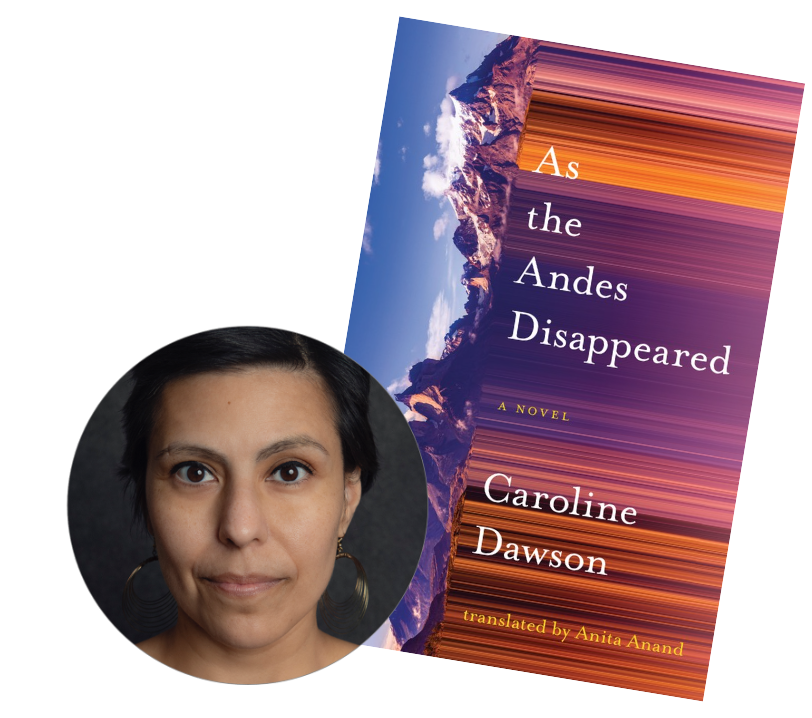

When a person is exiled from a mother country to “a better world” and feels a disconnection with everything around them, we need to acknowledge that there is a price—a big price—involved in restarting a life and building new connections. You also can’t do it alone. As a sociologist, I believe that people belong with each other, and that there’s no such thing as a self-made man. We need stories to understand that powerful thought.

– Caroline Dawson, As the Andes Disappeared

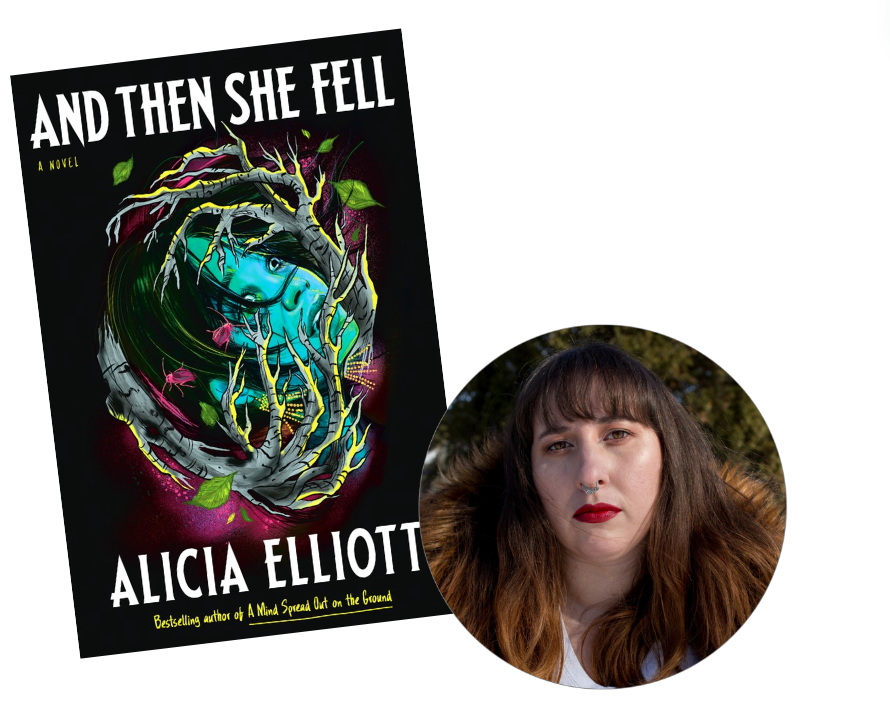

Alice, my character, is Haudenosaunee. For centuries, her people pointed out the ways in which our world is not only interconnected, but interdependent. Each part of creation relies upon other parts to remain healthy. That sort of interconnectedness isn’t conducive to colonialism and capitalism. For those to thrive, humanity’s connection to creation must be destroyed. We are living in the wake of this ongoing destruction. Disconnection is the modern condition.

Alice’s journey is one of reconnection—not just to her daughter, family, community, and culture, but also to the land she currently lives on in Toronto and the creatures that call that space home. Most pressingly, she needs to realize her responsibility to her descendants, who will rely on her one day. While Alice’s experience of what we call “reality” is not the same as those around her, I would argue that her understanding of her place in relation to time and creation are much more realistic than the collective delusion we currently live under, wherein present profit margins are all that matter and the ruthless pursuit of them brings no consequences. The world we live in, and the disconnection and callousness it fosters, that’s actually “crazy.”

– Alicia Elliott, And Then She Fell

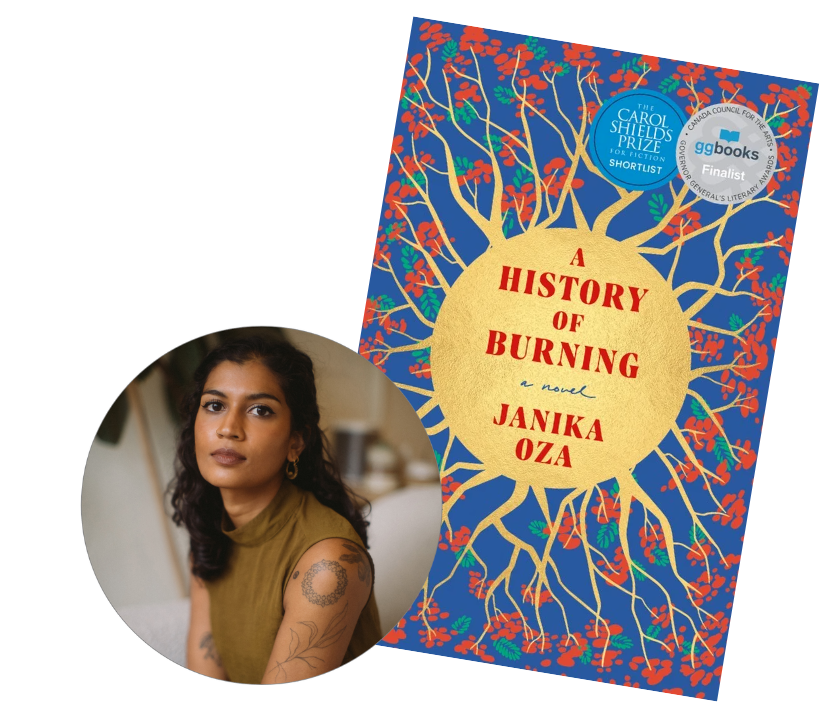

A History of Burning is about a family that goes through multiple forced migrations and experiences of displacement—from India to Uganda and to Canada and the UK—and the ways they fracture and come back together time and time again. For my characters, the connection to home is constantly changing, constantly unsettling and resettling. There is no final arrival. Through the four generations of this family, the novel explores what fragments of memory and story are passed down, buried, or stored in the body. It asks: what do we keep carrying?

The book asks what it means to come back to your kin, to find rootedness, or wholeness through community: whether it be a family, a land, or a movement. That idea of community and collectivism is really at the heart of the novel, and it holds so much more weight when a community has been ruptured. I wanted to explore what kinds of return are possible when you can’t return to the land you once called home.

– Janika Oza, A History of Burning

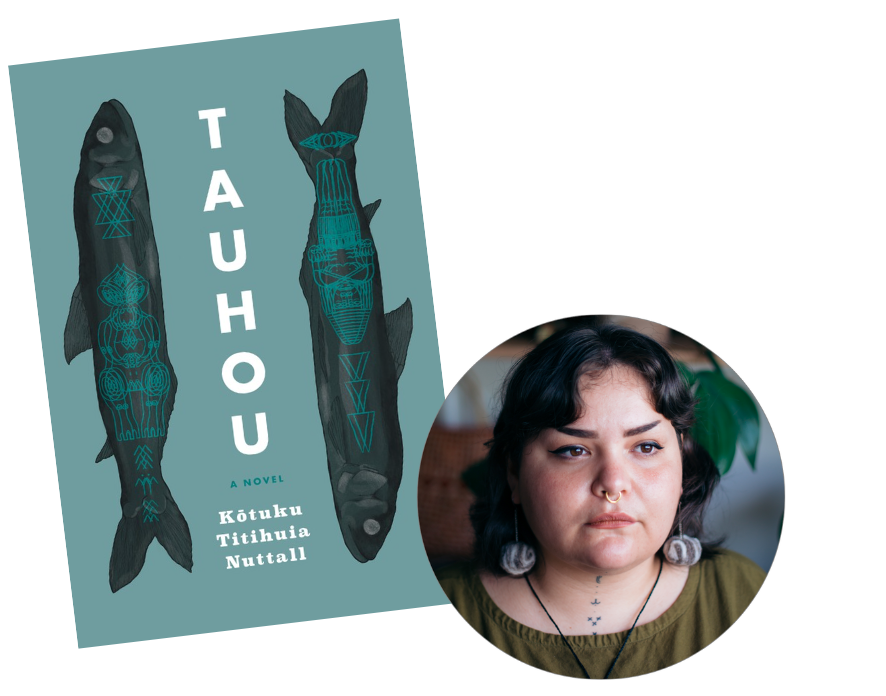

I had to write myself new connections to my history and my culture. My father was a gatekeeper—a “missing stair”—who purposely made himself my only connection to being Coast Salish. With Tauhou, I took back control of my identity and reached back past him toward my grandparents, great-grandparents and their other descendants—aunties and cousins—who shared love for our people and culture. Other parts of Tauhou are inspired by my mother’s family. Her story as a mixed Māori and Pākehā woman is just as fractured, confusing, and defined by disconnection and reconnection. She raised me to be empathetic and proud, to surround myself with safety and to imagine beyond.

Tauhou is an attempt to bridge a 7,000 mile gap between New Zealand and Canada; two nations which share a great deal, especially the exceptional, forced alienation of Indigenous people from their lands, languages, cultures, and histories by the government and the Crown. I found myself writing characters like me back into parts of our cultures and histories, filling in gaps left by colonialism. I needed the characters to be queer, liminal, in-between, and otherwise. I wanted to write my love for the women in my life: past, present, and future.

– Kōtuku Titihuia Nuttall, Tauhou

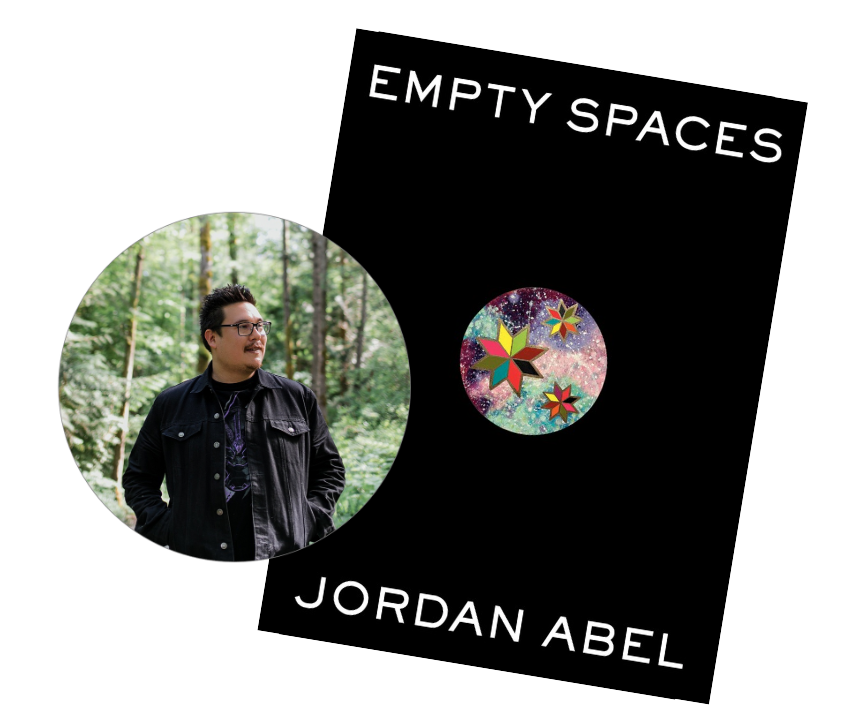

Empty Spaces is a difficult novel to synopsize. Partly, it is a book about Indigenous dispossession, the afterlife of attempted genocide, and the necessity of fiction in thinking through my relationship with the land. It is also work that is indebted to what Sina Queyras calls “lyric conceptualism,” a methodology that for me included an elliptical process of writing and rewriting. I often resist talking about Empty Spaces as an Indigenous rewriting of James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans because I think that oversimplifies the project, but that is also one of the origin points for this novel.

The allegorical elements of the book—which are also the parts about dispossession—underpin the methodology. The only way I was able to access land that I have been dispossessed from was through fiction, through imagination, through metaphor. In order to write about my relationship with land that I have been removed from, I had to turn to process, to write and rewrite, and return to sentences that had been written before and to write over them, beyond them, through them, and with them. Dispossession is at the heart of this work, but reclamation is right there too.

– Jordan Abel, Empty Spaces