For Michael Center, 2019 was shaping up as a hell of a year. After almost two decades as the coach of the Texas men’s tennis program, Center had assembled a team capable of winning the NCAA title. His two top singles players were blazingly talented, perhaps the strongest recruits he’d ever had. All season, the Longhorns thrashed opponents.

On the third Sunday in May the Longhorns would fulfill their promise, defeating Wake Forest in Orlando to win their first national championship in the program’s 73-year history. Center watched the matches with pride, wearing his trademark burnt-orange T-shirt and a considerable smile.

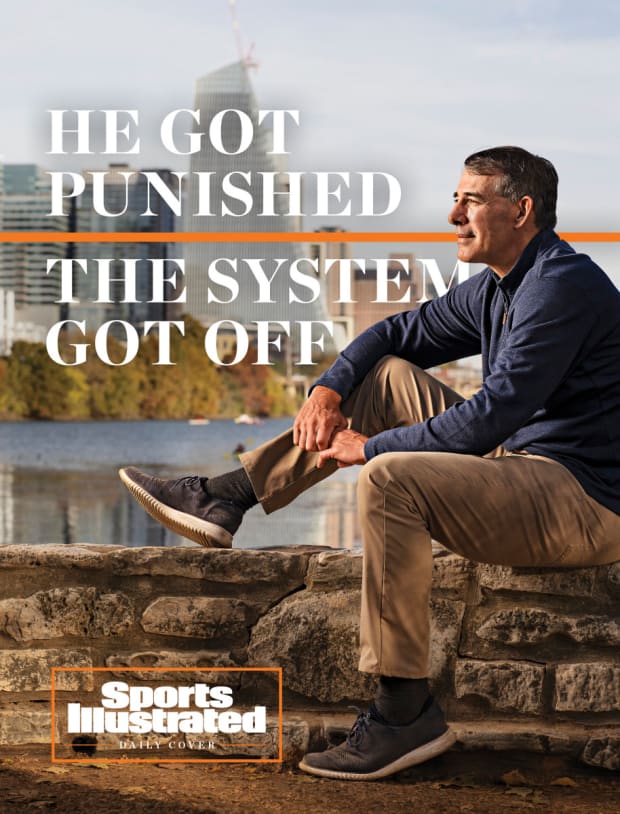

But as a dogpile ensued on the court, Center was home on the couch, suddenly in tears and unsure how to feel. “It was a dream day,” he recalls, “and it was also one of the most difficult moments of my life.” It didn’t help that ESPN’s broadcasters had referred to Center as “a distraction.” When the team FaceTimed him an hour later, he fumbled through a few words of praise and then cried again.

Darren Carroll/Sports Illustrated

Center was one of the nine college coaches sentenced in Operation Varsity Blues, the 2019 college admissions bribery scandal. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who has paid a steeper price. Texas had fired him and, within a year of his players’ triumph, he was serving a six-month term in a federal prison in Three Rivers, Texas, three hours south of Austin. On intake, he was put on suicide watch: His cell contained a concrete bed and a plastic mattress with a pillow sewn on top. The air conditioning didn’t work. The lights remained on at all times. “I begged the guard to place a fan at the bottom of my cell so I could get some air,” Center says. “The guard told me he didn’t want another Jeffrey Epstein. I started to cry and thought about bashing my head against the wall. Then I got COVID.”

For all that, Center says that rock bottom had come months earlier, in September 2019, when he received an email of a Texas news release signed by the university’s president. It stated that an internal Varsity Blues investigation had found that the coach was solely responsible for any stain on the school: “Because Center’s conduct was unthinkable in athletics, the controls in place did not catch his subterfuge.”

Center says he was never contacted for the investigation, which was performed by the university’s vice president of legal affairs, not an outside firm. Since the beginning, the coach has admitted wrongdoing: He had sponsored a recruit for admission who had no intention of ever playing on the team. He later took a $100,000 payout. But the idea that he acted alone? That no one else in the entire athletic department—a workforce of more than 300, with seven employees dedicated specifically to “risk management and compliance services department”—was also at fault? That others weren’t fully aware that the university was admitting a nontennis player to play tennis?

“I almost fell out of my chair,” says Center. “I literally couldn’t breathe. There’s no college coach in America—much less at a state school, much less a coach of a nonrevenue sport—who can admit an athlete without consulting other people in the athletic department. What they were asking people to believe, it’s just impossible.” Multiple coaches at UT—and administrators at other schools—confirmed this characterization to Sports Illustrated.

Almost three years on, Varsity Blues triggers more smirks than outrage. The quintessential American scandal, it combined kids, sports, celebrity, privilege, college admissions, bribery and schadenfreude. So far, 29 of the implicated parents—including actors Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin—have been sentenced to a median of two months in prison and $150,000 fine (which was less than half the amount of the median bribe). Their children, often unaware of the fraud perpetrated on their behalf, were put through the social media wringer. (Who didn’t giggle at the fraudulent USC water polo recruit whose backyard pool image was Photoshopped into a water polo action shot?)

Despite cooperating with the feds, Rick Singer, the chief architect of the scheme, is awaiting a sentence that could be as heavy as 65 years in prison. And the world got a glimpse of the transactional underbelly of college athletics and admissions, where money and power could buy so much.

Yet the system got off astonishingly easy. Athletic programs nationwide, as determined to maximize revenue as ever, chug on unbothered. School administrators and athletic department officials may have written self-flagellating mea culpas about the “need for better controls.” They may have vowed to examine the various loopholes for athlete admits. They may have, rightly, fired coaches—all in nonrevenue sports—who accepted bribes. But no athletic directors or school presidents faced job loss, much less criminal charges.

So it is that the ultimate scandal might be this: Nothing has meaningfully changed. As it stands, Varsity Blues is like an organized crime dragnet that had the goods on the low-level crew members. But instead of rolling them up and going after the capos and taking down the syndicate—the feds accepted guilty pleas, held self-congratulatory press conferences and then headed off to the next case.

Matt Marriott/NCAA Photos/Getty Images

Michael Center’s saga begins in 2013 when DeLoss Dodds, UT’s longtime athletic director, retired. Dodds’s replacement, Steve Patterson, was younger, slicker and boasted a flashy résumé that included time with the Texans, Rockets and Trail Blazers. He’d spent the last year as AD at Arizona State before hopping to UT.

Patterson concedes that he and his top lieutenant, Chris Plonsky, made clear: Nonrevenue sports needed to carry their financial weight, which meant coaches needed to fundraise like never before. Texas athletics might rake in revenue—$200 million, even in COVID-19-riddled 2019–20, the most recent year with figures available—but Patterson emphasized that income from media deals and ticket sales needed to be augmented by donations. Patterson told SI this was less about philosophy than economic necessity: His department was “$15 million in the red” when he started.

Under Dodds, Texas had earmarked $15 million for a new tennis facility; the old one was to be demolished to make way for a medical complex. Under Patterson, that line item was gone. Center recalls the AD saying that if he wanted a new home for his program, “people needed to pull out their checkbooks.” He also says Patterson told him that if he reached $10 million in private donations, “a shovel would be put in the ground.”

Center says that, grudgingly, he began to court donors. And he scored an early success when the father of a former player indicated a willingness to contribute $5 million toward a new tennis center in exchange for naming rights. Before the 2014–15 school year, all of UT’s coaches gathered at Patterson’s home for a kickoff dinner. The university’s then president, Bill Powers, stood and cited Center by name for the $5 million donation he was on the verge of closing. “I was pleased for the recognition,” says Center, “but thought, Funny, we won the conference and finished in the top five in the country last season, and I never heard anything from the administration.” That summer Center received a new five-year contract. (Patterson says he persuaded the UT board to give Center a 30% raise in recognition that the facilities situation had made his job difficult.)

The $5 million gift, however, fell through. Center says that he felt intense pressure, fearing that if he didn’t raise the funds he wouldn’t get a new facility, which meant he wouldn’t get top recruits and then wouldn’t get his next contract. “There was a naked interest in bringing in dollars,” Center says. “I was a fundraiser first and a coach second.”

Around that time, in late 2014, Center received a call from Martin Fox, a longtime tennis coach from Houston who had entered into the murky world of AAU basketball. A classic connector, Fox ran a team and steered recruits to colleges and universities.

Fox asked Center for a favor on behalf of a friend, Rick Singer. Based in Newport Beach, Calif., Singer ran a college consultancy business and one client, a wealthy Silicon Valley private equity titan, Chris Schaepe, had a son who wanted not only to attend Texas but also to become a manager on the men’s basketball team. Could Center help get him admitted under the guise that he was a tennis recruit?

Center recalls being confused. The basketball program had, as he puts it, “infinitely more juice” than tennis. What’s more, Schaepe supposedly had Bay Area connections to Kevin Durant. Why wouldn’t the family lean on Durant, the most prominent player in Longhorns history, for help? But Center agreed to entertain the offer. “Special favors,” he says, “happen all the time in college sports.”

The plan was simple. Center would recommend Schaepe’s son for admission as a tennis player, though, for all he knew, the kid didn’t know how to grip a racquet. Center’s recommendation then would have to be approved by a long chain of administrators—all of whom could have been expected to note that the applicant did not play tennis (and in fact hadn’t since he was a high school freshman). That chain would include the academic support staff, the compliance office, the sports supervisor and, ultimately, the athletic director. The applicant would sign a national letter of intent as a tennis player and receive a book scholarship. Then, upon arriving in Austin, he would renounce his interest in the sport and instead work as a basketball manager.

Coding the kid as a “recruited athlete” would reduce the academic requirements, improving his chances of admission. The basketball team would be getting a student manager with high-octane connections. Center would not lose a scholarship or roster spot, and, he notes, within the athletic department, “I would be considered a team player.”

And, crucially, there was the sloshing of money. Fox, by all accounts, the hub of communication for everyone involved, told Center that Schaepe and his wife, Jennie Chiu, were prepared to contribute $100,000 to Texas athletics, earmarked for tennis. And that might be just the beginning.

In October 2014, the student—then a high school senior—met with Longhorns basketball coach Rick Barnes to discuss becoming a manager, according to a person with knowledge of the meeting. In March ’15, Barnes took the head job at Tennessee and was replaced by Shaka Smart. Center wondered whether this might squelch the plans. It did not. Fox, says Center, quickly assured him that the basketball program “[still] really wanted this to happen.”

And it did. According to Center, he met with UT’s academic support staff and assured them that the kid would never play tennis, that this was really a fundraising mission. Academic support prepared the national letter of intent and sent it to the compliance department. Center provided SI with a screenshot of his text exchange with a compliance official confirming that the prospect would never play tennis for Texas and that he would relinquish his book scholarship in the fall. Dated June 11, 2015, the official’s text read: “Is Chiu-Schaepe even going to be a participant or will that cease after the fall? Was just thinking the voluntary relinquishment rule is typically for those who are no longer a part of the team so wanted to be sure.”

Center replied: “Will not participate.”

“There are forms and signatures and paperwork and on-boarding and housing,” says Center. “Everyone in the [athletic] department knows who [the recruits] are.”

It all played out as it had been presented to Center: Upon arriving in Austin in the fall of 2015, the new freshman renounced his interest in tennis and moved into an athletic dorm as a student manager for basketball, a paid position.

Barnes declined comment for this story but said through a spokesperson that, at Texas, student managers were assigned to teams through the athletics equipment staff. Smart denied to SI that he knew how the student was admitted. Now an independent sports consultant, Patterson denied knowledge of any scheme. Plonsky referred SI’s request for comment to a university official, who referenced the UT internal review, which named only Center. Asked why their son would have signed his letter of intent if he did not intend to play tennis, a Schaepe family spokesperson said, “The Schaepe family had no prior experience with collegiate athletics and understood that this NCAA paperwork was applicable to student team managers.”

And as planned, Schaepe became a big donor. In July 2015, he contributed $100,000 to UT tennis. Shortly afterward, Schaepe and Chiu gave additional six-figure gifts to the communications school. Schaepe also donated stock later valued at $625,000 to Singer’s foundation. (“The Schaepes acted lawfully, were not charged with any wrongdoing and were unaware of others’ unlawful conduct,” their spokesperson said. “Their donations to UT over several years were made through UT’s development offices only after the student’s acceptance and not promised in advance.”)

After Schaepe’s son was admitted, Singer’s blog included a picture of the student with Kevin Durant. The caption: “Hey Rick, I wanted to thank you personally for all the help getting me into the University of Texas in Austin, and helping me secure a manager’s position with the UT basketball team.” Curiously, the name of Schaepe’s son was misspelled on the post. The family asserts, through a spokesperson, that the rumors that they even knew Durant were false. It was another bit of Singer’s deception.

Bob Daemmrich/ZUMA PRESS Wire

That summer, Center made what he characterizes as “the worst decision of my life.” He took a call from Singer. While Fox, who declined comment to SI, had been the connector—for which he would eventually be sentenced to three months in prison and a $95,000 fine—clearly Singer was the driving force behind the scheme. And Singer had some good news. He had already paid Fox $100,000 for his liaising. Now it was Center’s turn. “He told me I was personally entitled to $100,000,” Center recalls. “It was clear [Singer] wanted to run this play again in the future.”

In June 2015, Center agreed to meet with Singer at the Austin airport, where Singer was passing through. In the parking lot of an airport hotel Center accepted a backpack containing $60,000 in cash. (According to Center’s indictment, the other $40,000 came in checks he sent on to the Longhorn Foundation, he says earmarked for tennis.)

“Why did I do it?” says Center. “I go to bed and wake up each day asking myself the same question. I had to convince myself that I somehow deserved the money. Texas had just cashed a big check [from Schaepe], and nobody had any issues with that. . . . I was in my early 50s with a wife and two kids. It was my turn. Almost immediately, I knew I’d made a mistake. I put the money in my basement and gave most of it away. It felt dirty. But, yeah, it was a horrible lapse in judgment, and it’s my responsibility to tell the truth and own it.”

Center says Singer called him again in 2016. He had another client seeking admission at Texas. “It was a quick call,” Center recalls. “I said I had no interest.” In early October ’18, Singer called again, cryptically, wanting to discuss their “deal” from ’15. Center offhandedly recalled a few of the specifics but said that he was in an airport and that if Singer had more questions, he should email.

In Center’s retelling, he was not exactly a man freighted by the guilt of having committed a crime. He says that he seldom thought about Singer or his machinations. Center was consumed by his family, the tennis team and its prospect for winning a national title. “Life,” he says, “was good.”

Until suddenly it wasn’t. On March 12, 2019, Center had no idea why FBI agents were storming his home and shackling him. “There must be some terrible mistake,” he recalls saying. “Everything is sealed,” the agents responded, presumably referring to his indictment.

After spending most of the day in detention, Center met with a lawyer, appeared before a local judge and was released on a $5,000 bond. Little did he know that by then Varsity Blues was already riveting the country.

A media swarm had gathered outside the courthouse in Austin; when Center emerged, he told them to go watch his team play that night, because that would be far more interesting than anything he had done. At that point Texas had sent Center an email informing him he was being fired from a job that paid him $232,000 annually.

Center soon learned that when Singer had called him that past October to rehash the details of their 2015 arrangement, he was acting as a cooperating witness and the FBI was recording the call. Singer was the central player, funneling kids into college by all means, including hiring instructors to take their SATs. But the use of venal college coaches to ease the admissions process became an effective side door as well. Especially when parents like Schaepe—who was let go by his venture capital firm amid the scandal—could follow up with hefty donations.

“I knew I had to answer for my guilt,” says Center. “But I was like, Man, schools are going to get hammered.”

Darren Carroll/Sports Illustrated

Because this was a federal case brought by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in the District of Massachusetts, Center hired local Boston counsel. When he and his lawyers met with U.S. attorneys, Center explained that, yes, he had played a role, but it was as part of a widespread scheme.

He produced the text exchanges with UT’s compliance official. Center also mentioned Plonsky, the longtime executive in the athletic department. In 2015 her duties included overseeing men’s tennis, compliance, academic support (which generates letters of intent) and the Longhorn Foundation. How, asked Center, was it remotely plausible that she was unaware that the son of a major donor had been falsely admitted as a tennis player?

“I was no rogue actor,” Center says, “and this wasn’t my word against their word. There were signatures that went along with it. That’s the system. . . . There wasn’t one point in the process where I thought people wanted to learn the whole truth.”

Center was told that his recommended sentence would be 15 to 21 months, provided he pleaded guilty to all charges within 24 hours. Low on both options and funds, he says, Center pleaded guilty to a single count of conspiracy to commit mail fraud and honest services mail fraud. His sentence consisted of six months in federal prison, one year of supervised release and repayment of $60,000. At sentencing, U.S. District Judge Richard Stearns said that Center’s actions “impugn the entire integrity in something that this country is so proud of—and that’s the education system in this country.” Stearns made no reference to UT or other complicit administrators or a corrosive system.

Why would the U.S. attorneys settle for the indictments of parents and coaches of nonrevenue sports when they could take down bigger fish? The answer might lie in the nature of the charges filed. In a federal fraud case, the government must show a “deprivation of money or property”—for there to be fraud, by definition, someone or some entity must have been defrauded.

Who, specifically, was defrauded by the Varsity Blues scandal? “The [prosecutors] made noise,” says former federal prosecutor Randall Eliason, now a professor at George Washington University Law School, that “this is an affront to all the good, hardworking students who couldn’t get into college because of shenanigans like this. But that wasn’t how they [made] their case.”

He’s right. As in the 2018 NCAA basketball corruption probe, the Varsity Blues prosecutors asserted that the schools themselves were the aggrieved, defrauded party. The government’s theory in ’18: When shoe companies and middlemen pay recruits, the schools are deprived of eligible athletes. Likewise, when coaches took bribes from Singer, they deprived schools of their honest services.

This theory holds if renegade coaches enrich themselves at the expense of the school. It unravels, however, if the schools are part of the scheme. “If [prosecutors] go after the head of the athletic department, at some point they’re undermining their own case,” says Eliason. “If the senior people are in on it, the schools aren’t being defrauded. They’re just playing the game like everyone else.”

Eric Rosen, a former federal prosecutor who led the Varsity Blues case and is now in private practice, pushes back on this idea: “Even if the entire athletic department is in on it, it’s still a crime. If they’re deceiving the admissions department by funneling through fake athletes, that’s fraud. One department doesn’t have license to rip off an entire [school].”

So why didn’t Varsity Blues implicate more high-ranking officials at the schools? “Prosecutors go where the evidence takes them,” Rosen says. “If it were a school policy to accept fake athletes in exchange for money, it probably would not be a crime. But admissions thought these were legitimate athletes recruited to play on their teams. And they weren’t.”

But it remains an open question: What did admissions, and other administrators, know at each of the eight Varsity Blues schools? Consider Stanford. There, sailing coach John Vandemoer designated two applicants as athlete recruits, without vetting them. In exchange, he received $770,000 from Singer. Neither student matriculated to the school. And Vandemoer kept none of the funds personally, instead investing them in the Stanford sailing program.

Vandemoer recalls that when he mentioned Singer, other members of the athletic department spoke glowingly of him. “He’s a guy you can trust,” Vandemoer remembers Stanford assistant basketball coach Adam Cohen enthusing.

Vandemoer says he handed over a check for $500,000 from Singer’s charity—part of the $770,000—to a fundraising administrator in the athletic department. Pleased by this windfall, she summoned Bernard Muir, Stanford’s AD. According to Vandemoer, when he began to explain that the checks came from Singer, his boss cut him off. “Oh, we know Rick,” said Muir. “We know Rick well.” (A Stanford spokesman tells SI: “Coach Cohen does not recall ever endorsing Singer. . . . Stanford’s athletic director never met or spoke with Singer and had no relationship with him.”)

After being indicted, Vandemoer was fired. He would plead guilty to one count of racketeering conspiracy and be sentenced to one day in prison, six months of house arrest, two years of probation and a $10,000 fine. A subsequent external review commissioned by Stanford found no evidence that any other employee of the athletics department had “agreed to support a Singer client in exchange for financial consideration.” It did, however, note that Singer “directly or indirectly approached seven Stanford coaches about potential recruits between 2009 and 2019.”

Vandemoer was floored. “I didn’t buy for a minute that I was the only one who’d been taken in by him,” he says. “Why would Singer keep coming back, year after year, if his efforts weren’t bearing fruit?” He made those points in a book published last fall, Rigged Justice: How the College Admissions Scandal Ruined an Innocent Man’s Life.

“I get asked, ‘Will this be the difference? Will this change these schools?’ ” Vandemoer says, referring to the scandalous publicity around Varsity Blues. “My simple answer is ‘no,’ because the people in charge are the problem.”

Vandemoer has been diagnosed with PTSD and “I still have my moments,” he tells SI, “my nightmares, when the anger, the frustration comes back.” But he’s found catharsis talking about his ordeal. And he is back on the water, coaching kids, ages 10 to 13, in Redwood City, Calif.

Center has had a rougher go of it. For one, he spent months inside a 10-by-10-foot cell and experienced firsthand the defects and vagaries of America’s criminal justice system. When he contracted COVID-19 in the summer of 2020, his denial for transfer to home confinement was rejected because the judge misread the file and believed Center was a college tennis player in his early 20s—not a former college tennis coach in his early 50s.

Since his release in August 2020, he has struggled to find employment and fulfillment. Opposed to uprooting his wife and teenage sons, he decided to remain in Austin. But that means constant exposure to the institution he feels betrayed him. “There are,” he says, “triggers every day.” Like Vandemoer, Center says he has benefited from therapy and that Varsity Blues has left him with PTSD.

Center says that, at his lowest moments, he has leaned on the same advice and bromides he spent years dispensing to his athletes. Tell the truth. Own It. Forgive yourself and then forgive others. Rise to the occasion. Pressure is a privilege. Some of them ring true. Some ring hollow.

He catches himself when he reflects on one adage, in particular. “I was always taught that actions have consequences,” he says. “I said that one all the time. What I’ve come to realize is that, yes, for some people actions absolutely do have consequences. Serious, heavy ones. For others, actions can have no consequences at all.”