Scott Morrison recently announced a $2.2 billion Research Commercialisation Action Plan for the next ten years. The plan centres on a competitive grant scheme to promote start-ups and industry partnerships. The prime minister’s message to universities was clear:

“we need to find and develop a new breed of researcher entrepreneurs in Australia”.

The statement came on the heels of a letter of expectations from the acting minister for education and youth to the Australian Research Council in which he encouraged greater collaboration with industry, particularly the manufacturing sector.

Read more: Latest government bid to dictate research directions builds on a decade of failure

What might we expect from the rise of researcher entrepreneurs in Australian universities? Who are likely to be seen as exemplars of this new breed?

Given the male-dominated makeup of the industry partners who are meant to lead the commercialisation of research, what we might realistically expect is a major step backward for gender equity in Australian universities.

Industry stakeholders’ gender gap

Workplace Gender Equity Agency data paint a grim picture. Women hold only 14.6% of chair positions and 28.1% of directorships in Australia. A mere 18.3% of CEOs and 32.5% of key management personnel are women. Gender equity in leadership roles has even gone backwards in recent years.

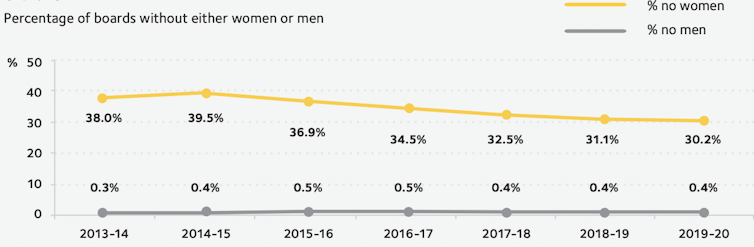

Nearly a third of boards and governing bodies have no female directors. By contrast, less than 1% of boards have no male directors.

Sociological research on business culture can shed light on why these statistics at the highest reaches of industry are so skewed. By understanding how the social networks that support business financing operate, we can begin to appreciate how industry partnerships are likely to be funded.

An investment culture of patronage

A recent insider account of investment culture in one of the largest hedge funds on Wall Street focuses on the analysts and traders who manage large financial portfolios. In her book Hedged Out: Inequality and Insecurity on Wall Street, Megan Tobian Neely offers a peek into the highly competitive world of corporate power brokers who make up the financial elite.

Neely’s ethnography follows those connections through what she calls a system of patronage. That is, using one’s own status and power to invest in, support or promote another person. For financial elite at hedge funds, she writes:

“patronage is how a select group of white men groom and transfer capital to other elite white men”.

So, entrepreneurship is not a gender-neutral term. The tight-knit networks that are the source of investment capital create a system of patronage that has redefined the capacity to manage risk and insecurity as a masculine attribute.

It’s not that women are pushed out of the boardroom on purpose. Instead, it’s about cultivating insiders. Protecting one’s investment means relying on investors who are like them, think alike, have the same values, who can help them get ahead, and who are overwhelmingly male.

Research on the professional managerial class in Australia suggests these patterns of patronage are not unique to the rarefied heights of Wall Street investing. Owen McNamara’s Canberra-based study of workplace culture in the Australian Public Service underscored the importance of what one of his research participants dubbed “making coin” from the industry network.

The integration of the public service with consultancy firms relies on a business culture suffused with male bonding. It’s not just locker-room talk. Networkers operate through the easy friendships, banter and camaraderie that comes from shared experience.

Women and gender-diverse people, as well as workers from different socioeconomic backgrounds, struggle to be included. And often they are the butt of the joke.

What about women’s networks?

These industry networks are the waters in which academic researcher entrepreneurs are expected to swim. These are the invisible social channels and patronage relationships that open the tap of investment.

Patronage relationships convince stakeholders in business to take a risk on unproven ideas. No matter how promising the research, it will be difficult to secure funding for researchers – particularly women and gender-diverse scholars – relegated to the outer edges of the network.

My research on women who start small businesses in Latin America indicates these are global challenges. There, women face barriers when trying to leverage their informal interdependencies and social ties, which often fail to convert into individual success and wealth.

Within universities, women’s informal networks and support mechanisms often translate into higher internal service burdens. This inward-facing networking includes undervalued work such as serving on university committees, program supervision, student recruitment and so on. Women, LGBTQIA+ and faculty of colour also do most of the extra invisible labour of making universities better and more equitable places to work.

These are not the advantageous external patronage connections that propel investments and business partnerships.

Can research commercialisation support gender equity?

We can’t simply add gender diversity and stir. Even once we recognise the problem of an insular network through which investment opportunities flow, the solutions aren’t easy.

How can we counter the troubling gender equity effects of pushing researcher entrepreneurs in universities? We can do this via two mutually reinforcing pathways.

First, we can strive for feminist organisational structures that more evenly distribute opportunities and decision-making power. This is an alternative to promoting academic #gurlbosses.

Read more: Why mentoring for women risks propping up patriarchal structures instead of changing them

Second, we might rethink the value of interdisciplinary scholarship in tackling wicked problems like gender injustice. This perspective is key to successful commercialisation and should not be deemed inferior to patents and inventions.

What good is a recovery plan for “building national resilience”, after all, if the benefits only flow to a select few?

Caroline Schuster receives funding from The Australian Research Council.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.