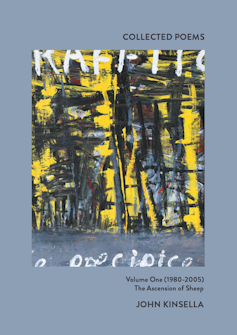

University of Western Australia Publishing has just released the first of three volumes of John Kinsella’s Collected Poems.

Subtitled The Ascension of Sheep, this monumental text (848 pages) covers the first 25 years of Kinsella’s writing, from The Frozen Sea (1983), which he published – as John Heywood – at the age of 20, to his remarkable New Arcadia (2005) which relocates (re-places) Sir Philip Sidney’s 1598 classic pastoral romance in the salt-blighted landscape of Kinsella’s native Western Australia.

Review: The Ascension of Sheep: Collected Poems Volume One (1980-2005) - John Kinsella (UWAP)

Between these landmarks, the new volume reproduces, in very close to their entirety, what Tony Hughes-d’Aeth in his introduction rightly calls a “dizzying sequence” of collections from the late 1980s to the mid 2000s – Night Parrots (1989), Eschatologies (1991), Full Fathom Five (1993), Syzygy (1993), The Silo (1995), Lightning Tree (1996), The Hunt (1997), Visitants (1999), The Hierarchy of Sheep (2001), Peripheral Light (2003) and Doppler Effect (2004) – along with numerous chapbooks and other small gatherings hitherto available only in limited editions.

Kinsella wrote many very fine poems during this period, some of them classics of their kind, and they are almost all here: “Dam and Globe of Death”, “The Disappearing”, “Drowning in Wheat” (“They’d been warned / on every farm / that playing / in the silos / would lead to death”), “Essay on Myxomatosis”, “Mala in se: death of an innocent by snakebite”, and “The Silo” itself, with its haunting conclusion:

… Before those storms

which brew thickly on summer evenings

red-tailed black cockatoos settled in waves,

sparking the straw like a volcano, dark

fire erupting from the heart of the white

silo, trembling with energy deeper

than any anchorage earth could offer.

And lightning dragging a moon’s bleak halo

to dampen the eruption, with thunder

echoing out over the bare paddocks

towards the farmhouse where an old farmer

consoled his bitter wife on the fly-proof

verandah, cursing the cockatoos, hands

describing a prison from which neither

could hope for parole, petition, release.

It is said Kinsella is the most prolific of contemporary Australian poets. I don’t know if that’s true – there are other contenders – but he’s up there. In 40-plus years of writing, he has produced between 40 and 70 books, depending upon how you count them.

Most of these books have been of poetry, and several have won awards, among them the Age Book of the Year, the Prime Minister’s Literary Award, the Queensland Premier’s Award, and the Western Australian Premier’s Award (three times). He has taught at Cambridge University, where he is a fellow of Churchill College, Kenyon College in Ohio, and Edith Cowan University.

Edward Hirsch in the Washington Post has called him “one of Australia’s most energetic and stormy poets”. Harold Bloom described him as “astonishingly fecund and inventive”. I would agree. Kinsella works at an astonishing pace. His creativity seems boundless. He hits the mark more often than he misses.

He is an activist, an avowed anarchist and pacifist, deeply committed to an interrelated array of understandings about the ways we should live in this world. I have long appreciated him as a vegan (he’s been so for more than 35 years), an environmentalist, and an advocate for nonhuman animals.

Read more: Friday essay: on being an ethical vegan for 33 years

And, for so long now that he must be seen as a pioneer, he has worked to incorporate these particular passions and convictions in his poetics. At Edith Cowan, he was one of the founders of the Landscape and Language Centre. Among his non-poetry books (though there’s a fair measure of poetry in them) are works like Contrary Rhetoric: Lectures on Landscape and Language (2007) and Activist Poetics: Anarchy in the Avon Valley (2010).

For a poet with such an international reputation, it may come as a surprise that Kinsella would claim, as he did in an interview some years ago (which I’m having great trouble finding again!), that all his writing has been focused on a small patch of land in the wheatbelt of Western Australia. I am not sure that’s true – call it a poetic conceit – but neither am I sure it’s entirely false.

Close attention to various patches of land in W.A.’s wheatbelt has taught Kinsella to see, and that seeing is, arguably, the watermark (or salt-mark) within almost all he now does.

If his poetry can be seen and understood as project (as I think it can: I think this is its real achievement), evolving into what he might describe as an ecopoetics, then these wheatbelt meditations are its core. They are an attempt to adjust the mindset and language of more traditional poetry to the needs of the ravaged landscape and the environmental crisis in which we find ourselves.

Language, attitudes and practices

Much of the language we have been bringing to poetry, and the forms and genres into which we have been shaping it, Kinsella would argue, have become imbued with the attitudes and practices that have led us to this crisis in the first place. To free ourselves from these attitudes and practices – to enable ourselves to see more clearly the extent and nature of the damage, let alone begin to do something about it – our language and our ways of using it have to change.

Philosophy has for some time been telling us our world is shaped by – is – language. Feminism, postcolonialism and other movements have long been aware that ghosts in the language (gender, racism, speciesism, and something else, a brutality and arrogance toward the environment) are a key part of their problem.

Australian poets have been aware of the various ghosts and carceral qualities embedded within language for decades now. But it is hard to think of any who have tried as hard as Kinsella to free our landscape, our views of landscape, and our thinking about landscape from them.

Look, for example, at a few short passages from “York-Spencer’s Brook Road”, one of Kinsella’s many “roadside” poems – poems for the most part drawn from a “natural” space between two points of human habitation, such as a car driver might encounter, pulling onto the side of a country road and stepping out, looking around. See how these passages track, within the space they view, the intersection of human and non-human networks:

I have a pavilion of land-folds in my vision, no

inland sea, just roadside drainage, scorched river, cored-mountain range

evoking leeward hills

…the valley, river running irregularly parallel to the road,

a fraction of its deep-hold self, running level and dry,

a treeline of flooded gums, York gums, jam tree,

roadside foliage as well. There are points where a polygraph

would detect a change, or take it as standard

to tell truth and lies of quartz against: flood points,

crests, the road so narrow cars almost touch

in passing

…The gravel has the taint of salt, white crystals

undoing laterite and clay, easing out of the run-off cut marks.

So, memory is sectioned out of the aerial photo,

and heavy haulage fragments the road edges. In this,

a theory of disaster, in the farmhouse centred in wasted

fields, the panopticon. Closely, a black-shouldered kite

hooks a mouse, and an unrecorded species of possum

feeds nightly on crown land, thin about the railway line.

This kind of tracking – of roads, fences, survey lines, water and electricity supply-lines, telecommunication waves, language, say, with vegetation, bird and insect life, weed cover, water level, salinity – and the way it is interwoven with local histories, memories, personal experiences, has become a feature of Kinsella’s poetic: an ecopoetic that entails a mode of seeing, a plurality of knowledges.

At its best, it can enable a poem, through its capacities for image, elision and juxtaposition, to condense networks and situations that might take an essay many pages to set out. It can also, intriguingly (the erosion, the wounds in the soil, detritus), bring to the textual space, as I think it does here, something of the quality of a crime scene.

The poem, then, as pantechnicon. The poet as polymath. To help rescue, to help halt the damage – to help undo the crime – one must know, one must inform oneself to inform others.

This knowledge, this steeping-in-place, the insistence upon it, not to mention Kinsella’s re-placing and interrogation of earlier ways of poetic seeing (“York-Spencer’s Brook Road” could be seen as an arid eclogue, an elegy or bitter satire in the ruins of an ode), is, I think, one of Kinsella’s gifts. .

Consider another piece, or set of pieces (“Sad Cow Poems” from The New Arcadia), for a glimpse of some of his others. “Affect flat as dung,” it begins,

… or sludge

that slicks the gradient, the young

that drive an udder, as if a word

for ‘cow’ might make cattle

might make beef and might

make muscles

on seasons of less light—

late sunrise suppressing melatonin

Our senses are immediately drawn in here (dung, sludge, slicks), but also strangely restrained. “[T]he young / that drive an udder” is clever, a nice conceit, but lines three and four are not so clear. In turning their attention to language itself, they make us suddenly suspicious of the very word (“cow”) upon which the poem seems to depend, as if a cow wasn’t itself somehow.

Lines five to eight introduce some animal husbandry (who knew suppressing melatonin can lead to greater body mass?), before the next lines –

and that bell, sounding out,

as silver as a twisting acacia leaf

driven by a wild front coming in

– sound a note as clear and clean as the one they refer to, pulling together and at the same time opening the poem, which (however) gives us then, as if to betray what we’ve just glimpsed:

to discharge the drought, the wanking machines,

gleam of the tanker

that’ll feed the cream separator,

centrifuge making heavy

water

This is only the first poem in a sequence of 17. Different as it is from “York-Spencer’s Brook Road”, we find in it that network again, the interaction of parts, knowledges and voices: anger (restrained), lyricism, understanding of processes (technology, milking), understanding of processes within those processes.

I’d like to visit more –

Molly B12 poked her head

through the door of the shack

most mornings. Her calf days

shortening. Some say pity

comes because of the size

of their eyes. Her eyes

were small, and their vocabulary

too immense for translation

– but I will jump to the last:

The stomach plug, flagrant to open

and check-up, ant colony of the chamber,

the enzymal action, belly business,

fragrant, busy, the reaching in

and pulling out the mush, like the bin-composter

that turns around on its metal frame,

the sort that local industry can build and market,

you just throw in your grass clippings and the like,

make of it that extra stomach.

A cow, with a port-hole in her stomach: a shocking emblem and indictment of industrial farming, another part of the damage.

Read more: Friday essay: species sightings

Expanding environmental knowledge

A few months ago, the editors of a forthcoming history of Australian poetry circulated a draft table of contents, indicating the volume would conclude with an essay on Kinsella, the only contemporary poet to be thus singled out. There were some complaints behind the scenes. People questioned why Kinsella should get this attention and not A or B or C.

I don’t know how the matter panned out, but I imagine similar questions might be asked of this volume. Why such attention to Kinsella, when so many other very worthy poets have no such accolade? Do we need so much Kinsella? And isn’t there a touch of self-contradiction in so dedicated an environmentalist sanctioning such an investment of trees? (Judith Wright declared, late in her life, she would rather save trees than publish more books of poetry.)

Fair questions, and I don’t discount these concerns. I must admit that when I first received the book, having agreed to review it, I was rather dismayed at its size. I wondered – still do – whether we need quite so much of Kinsella’s early work, and why he didn’t edit himself more aggressively. And, yes, I reflected too that there were others who could and probably should receive the same kind of serious and generous treatment.

But having lived with the volume for a while, and thought about its processes, I have come to see another side to the matter.

I wonder if UWAP, like the editors of the aforementioned history, might be trying to change or challenge the story and direction of our poetry a little, trying to make a statement that in this time of environmental crisis we, and our poets especially, as self-appointed legislators of our language, do need to think differently, do need to know more, do need to question our inherited assumptions and expand our environmental knowledges, and whether the apparent anointment of an experienced and dedicated exponent of “ecopoetics” might be, not an affront, but possibly, just possibly, the right thing to do.

David Brooks does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.