In my brief time with The Plucky Squire, I've saved a rocket ship from the scrap heap, used that rocket ship's son to jetpack around a toybox world, watched some heavy metal-loving sheep rock out on a mountainside, and entered a futuristic side-scrolling future to earn a rubber stamp with the power to stop time. Given that all of this happened within barely 45 minutes, I'm starting to feel as though the full package could prove to be yet another example of something that's fast becoming a beloved design principle.

Jumping into the game's sixth chapter, I'm not entirely up to date with everything that's brought me to this point, but I'm heading up a rock and roll-themed mountain, clambering through the pages of The Plucky Squire's 2D, picturebook aesthetic. Eventually, however, something bars my way - a fast-moving, industrial machine that threatens to mince me if I try to move through it. So, naturally, I'm encouraged to step off the pages of the book, into the 3D world around me.

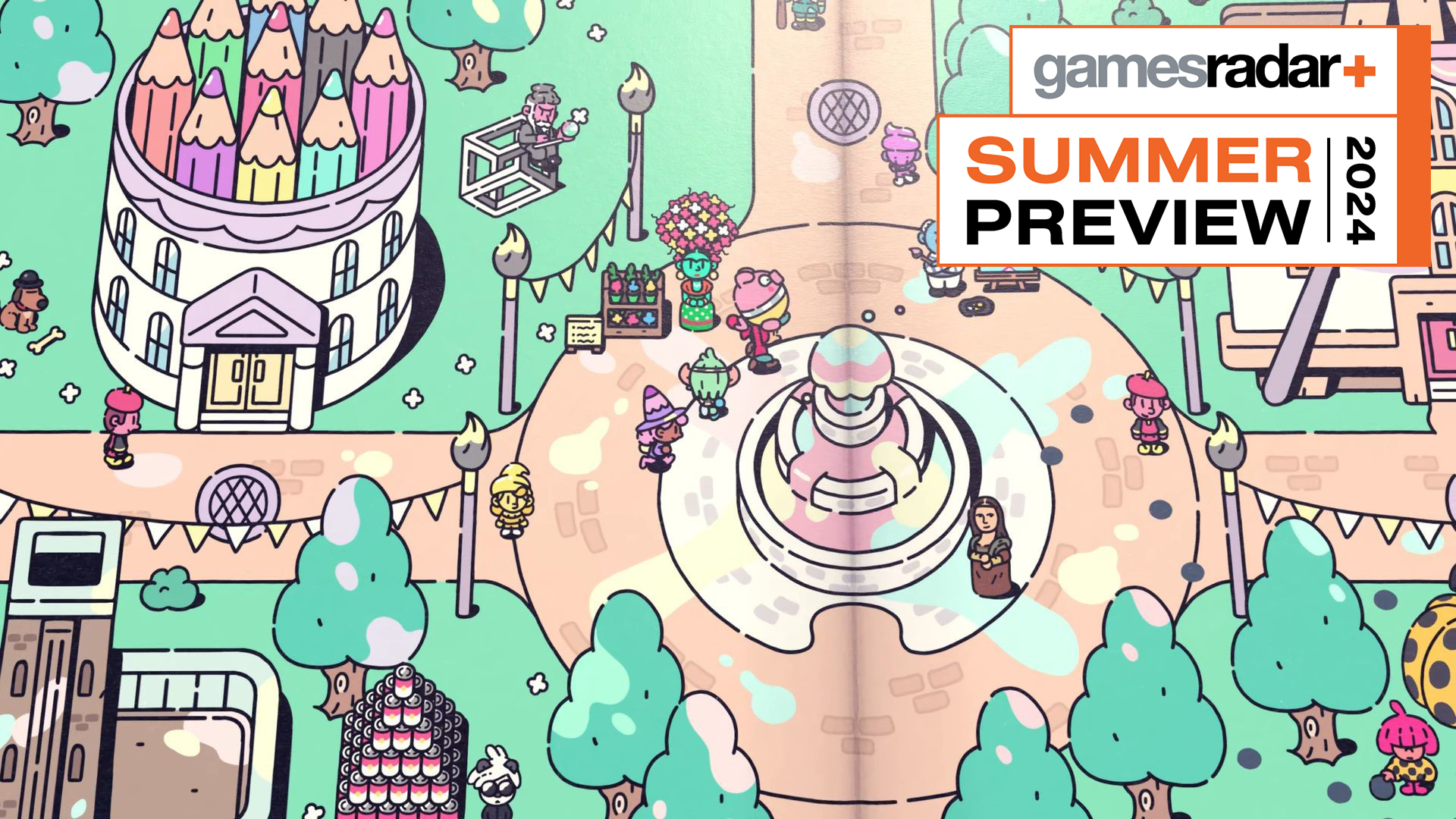

The Plucky Squire moves between the flat and the physical pretty often, encouraging you to jump out of the book and into the world. That world is the desk around the book, covered in blocks, toys, and mundane, everyday items that turn this new environment into a veritable platforming playground. As I hop around, however, I might find that my objective requires me to re-enter the 2D plane, jumping into the art on the side of a mug or toy, or simply into a different drawing, in order to advance.

Flat-pack

It's in those moments that The Plucky Squire tends to be at its most confident. In 3D, it challenges you with platforming and discovery, but in 2D it throws entirely new experiences at you. At one point, I'm desperately dodging back and forth between falling meteors. At another I'm gunning down incoming alien drones in an attempt to save some scientists to advance some far-future war machine. I realize as I chat with game director James Turner that I'm reminded of another game I played at Summer Game Fest - the constant feeling of novelty that I feel with The Plucky Squire is pretty similar to what struck me about Astro Bot.

In both of these games, the Mario Wonder-style feeling of something new around every corner turns what might have been a charming platformer into its own right into an ever-changing adventure. But where Sony opts for a bright, busy assault on the senses, The Plucky Squire is prepared to be a little more sedate, something more in keeping with the idea that you're both being told a story here and playing a part in it. Main character Jot is a quintessential storybook character, brought to life with a toy-like, plasticky quality in 3D and with a painterly style that reminds me of games like Chicory when he's still consigned to the page.

There's an obvious child-like charm that pervades The Plucky Squire. From Jot himself, to the way that toys shape the world around him, to the gentle timbre of the game's narrator evoking the telling of a bedtime story, there's an accessibility that evokes a certain era of platformer. As I move around the world, Turner is taking mental notes about signposting objectives, and we even discuss the potential inclusion of the kind of panning camera that I remember as a quintessential aspect of licensed PS2 games.

For all of the ways that The Plucky Squire talks to a bygone age, however, it's clear that it's also part of a new movement in this space. As the continual variation of the likes of Super Mario Wonder and Odyssey begins to be felt elsewhere - with games like this one, but also Astro Bot and It Takes Two - it feels like a new sub-genre is emerging, one that relies on the idea that you might understand the basic rules of the world you're exploring, but that one of those rules is that you can never be entirely sure what you'll find around the next corner. The Plucky Squire takes those ideas in its own direction, one that's perhaps even more innocent than some of its peers, making it an exciting point of progress in an exciting new space.