For Zoe Leonard, photography is not just about using a camera. Photography is also about a way of thinking, seeing and interacting.

This focus continues in her recent series Al río/To the River at the Museum of Contemporary Art.

An American artist who works across photography, sculpture and installation, Leonard’s work is wide-ranging in theme but always finely attuned to the role of photography in how the world is ordered and understood.

Interested in the role of photography in mapping and archiving, Leonard often turns her camera towards the uneventful and the everyday.

Leonard has photographed bricked up houses, with windows and doors closed up; and the trunks of trees pressing against fences. In Analogue (1998–2009), she observes the changing urban fabric of New York and the global movement of recycled objects and textiles in secondhand market stalls.

Queer politics also informs her work. Strange Fruit (1992-1997), a collection of fruit skins sewn together with thread, zippers and buttons, engages with loss, mourning and repair – an acknowledgement of the many who died in the early days of the AIDS crisis, including many of Leonard’s friends.

She is most famous, perhaps, for I want a president, a work she typed out in 1992. This work was given new life as a large scale installation on the New York highline during the 2016 US election, the same year Leonard began photographing the Rio Bravo/Rio Grande.

Movement and displacement

Al río/To the River surveys the stretch of river known as Rio Grande in the United States and the Rio Bravo in Mexico. The river marks the politically contentious border between the US and Mexico. Al río/To the River consists of photographs taken between 2016–2022 along the expanse of this river/border, but it is not straightforward documentary.

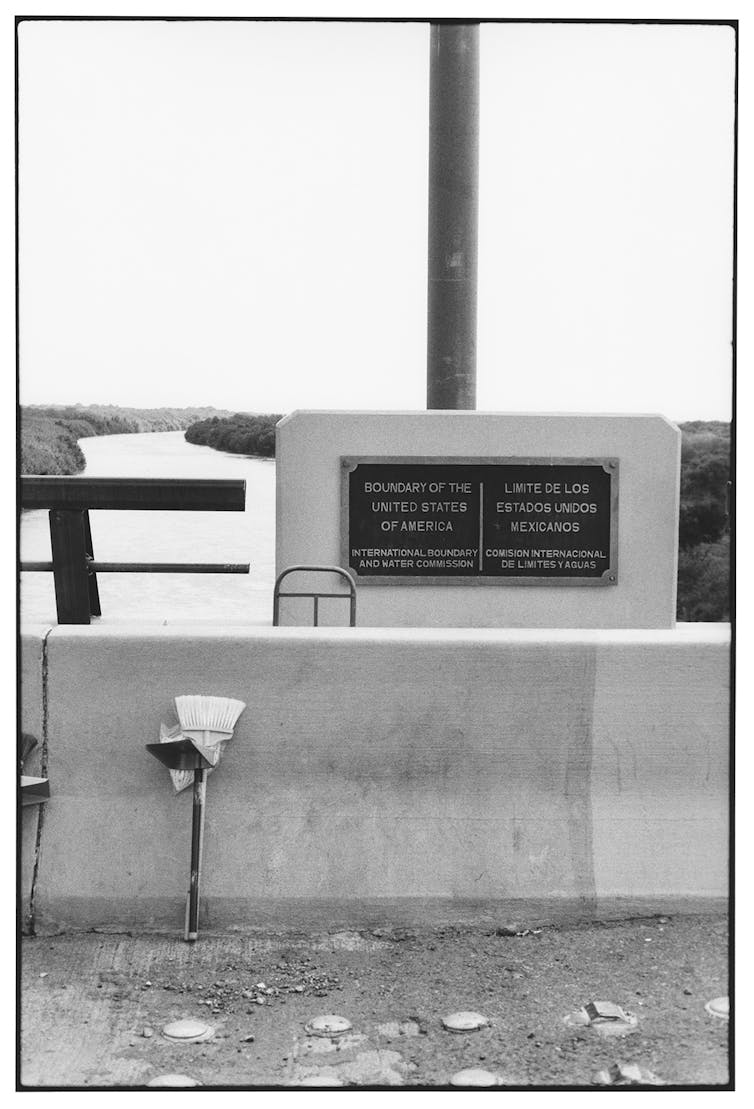

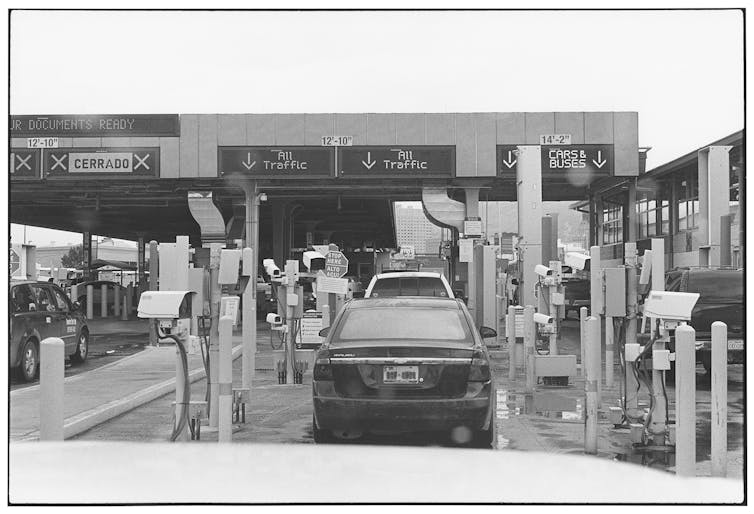

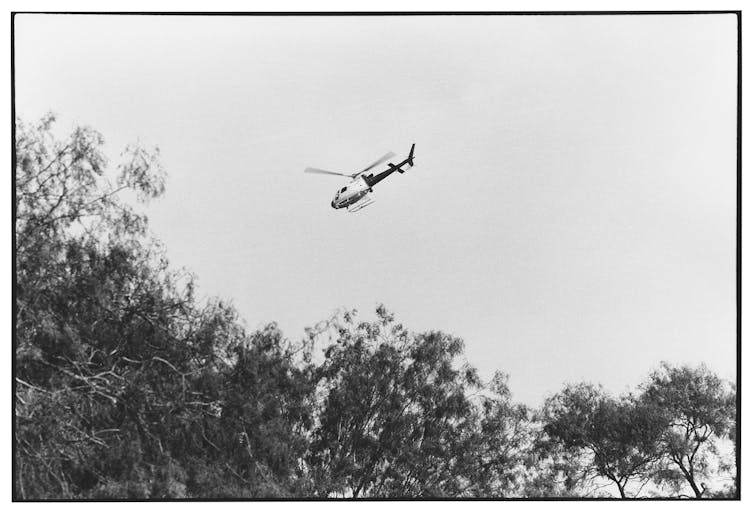

The images in Al río/To the River imply narratives about movement and displacement. They suggest the underlying hum of surveillance, industry and commerce. They observe the persistence of trees, soil and birds and the movement of water, as well as the rigidity of walls and bridges.

Like much of Leonard’s work, human subjects are often not directly represented. Instead, their presence and stories are felt through objects, structures, detritus.

In one image Leonard gives us the afterlife of a cleaning broom, resting at the border. The broom suggests the labour of cleaning, of workers who constantly negotiate the barrier between the two countries.

The exhibition is a complex portrait of the border that trades in traces. In one sequence of images Leonard focuses on the tyre and rake marks left on soil by patrol cars. Another image presents discarded tyres attached to rope, used by border patrol to flatten soil ready to reveal the footprints of fleeing bodies.

Another sequence of black and white photographs observes the lines of an agricultural field, and a flock of birds taking flight. By the end of the sequence the birds in flight almost fill the frame.

These moments of beauty and movement provide relief from other photographs which document the rigidity of fences and walls, the sharpness of barbed wire.

There is no singular vision here of the river. There is harshness as well as beauty, surveillance and flight.

Read more: Crossing the US-Mexico border is deadlier than ever for migrants – here's why

Fragments of a whole

While most of the modestly-scaled photographs are gelatin black and white prints, there are also some colour photographs. The colour appears in a sequence of photographs of bright pink flowers blooming on the ground and a set of close-up photographs of the river’s churning brown water.

At the end of the exhibition a series of iPhone photographs document a live-feed on Leonard’s laptop witnessing people migrating across a bridge.

All these photographs need to be understood cumulatively: each a layer or fragment of a more complex picture.

Leonard’s vantage point is unfixed, shifting. Leonard photographed from both sides of the river. Sometimes she pointed her camera skyward at ominous hovering helicopters. At other times she observes what is at her feet, or the cars queuing ahead of her at border checkpoints.

These vantage points are, of course, Leonard’s own. She emphasises this through her choice not to crop out the black edge of the negative. This thin black frame from the unexposed edge of negative film is a reminder these photographs do not give us direct access to the river/border. Our access is mediated – framed – by Leonard’s camera and position.

The lens flare on one image reminds us these images are the result of a relationship between a lens, the sun and Leonard’s finger on the camera’s shutter.

Al río/To the River is organised around a suite of rooms, and structured into passages which reflect the flow of the river it observes. The exhibition offers a spatial experience as much as a visual one.

In one room the windows reveal Sydney Harbour, which connects to a river with its own complex history. A wall in the same room is covered with a grid of 34 photographs: an echo of the photographic contact sheet, again showing how Leonard brings into conversation the matter, form and scale of photography with questions about the politics of looking.

Zoe Leonard: Al río / To the River is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, until November 5.

Read more: Here's a better vision for the US-Mexico border: Make the Rio Grande grand again

Image caption: Zoe Leonard, Al río/To the River (detail) 2016–2022 gelatin silver prints, C-prints and inkjet prints. Production supported by Mudam Luxembourg–Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, Paris Musées, Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Galerie Gisela Capitain and Hauser & Wirth. Image courtesy the artist, Galerie Gisela Capitain, and Hauser & Wirth © Zoe Leonard

Jane Simon does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.