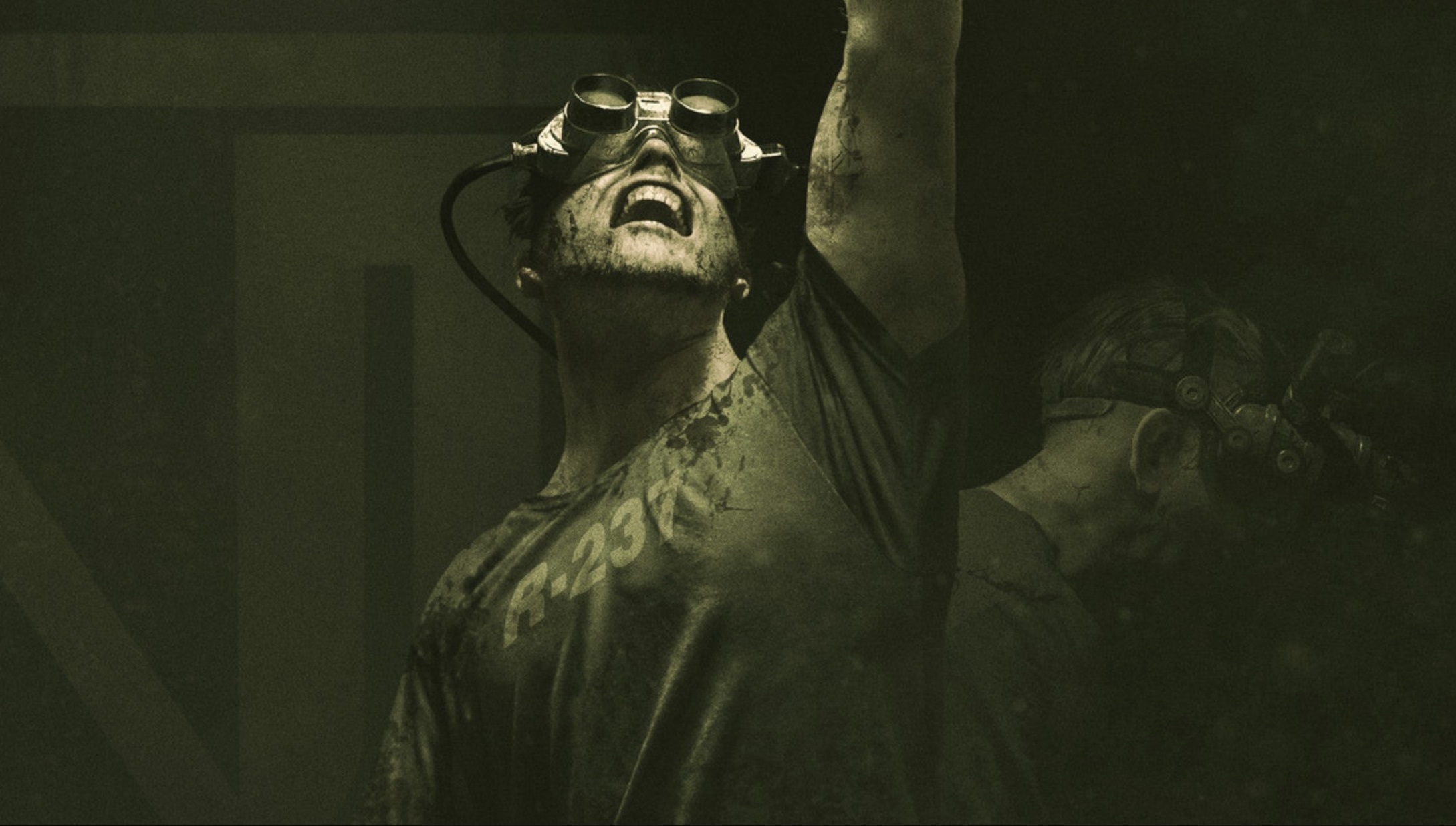

Outlast Trials earns its pre-game trigger warning within the first five minutes when a pair of boxy night vision goggles is pried off a dismembered corpse and screwed into your skull with an auger drill. You've been swept off the street to take part in the Murkoff Coporation's "Trials", an experimental group therapy program that targets those on the edge of society with something to hide that sees you and three other patients attempt to survive expansive Saw movie-esque puzzles. Outlast Trials' singleplayer introduction truly horrifies, but that terror quickly bleeds away in co-op, where I found the tension too often interrupted by janky key-collecting puzzles or frustrating, one-dimensional encounters with brutish psychopaths.

This brand of psychiatric violence really cut through to me in a way that stands very much apart from other horror games.

It starts strong, though. The Cold War setting and allusions to the disturbingly real MKULTRA and Operation Paperclip programs anchors it to our horrifying reality, with the test chambers you navigate often resembling underground counterparts to those fake cities built to test the effects of nukes, a "Nuketown" if you will. The opening level is a a faux plantation manor adorned with animatronic exhibits of the burdens you must be dispossessed of in the "Trials": your youth, your piety, your dreams, all for a chance at rebirth. It's never totally clear if you're someone truly harboring a secretive past, burdened by an undeserved guilt, or are just some everyman getting gaslit to serve as a control subject.

That tonal ambiguity is one of the keys to The Outlast Trials' terror. The first step of this process, as your smoke-spewing therapist loves to remind you, is being broken down, and you enter this world with a believably shattered sense of self. I found this setup uncomfortably easy to get immersed in—the researchers imposing this "therapy" on you speak in a general enough language that I felt it pass through the character I was playing as and peering right into some of the most repressed parts of myself, a level of fear and emotional involvement I was completely unprepared for.

"You've always been different, haven't you?" My therapist wryly remarked as I clutched a box containing microfilm records of my entire personal history—as a queer person, getting called out like this from a medical professional had me so unbelievably nauseous with fear that it brought back all the worst memories of being closeted, feeling like a freak needing a cure. It's heavy stuff, and may be too much for some, but this brand of psychiatric violence really cut through to me in a way that stands very much apart from other horror games.

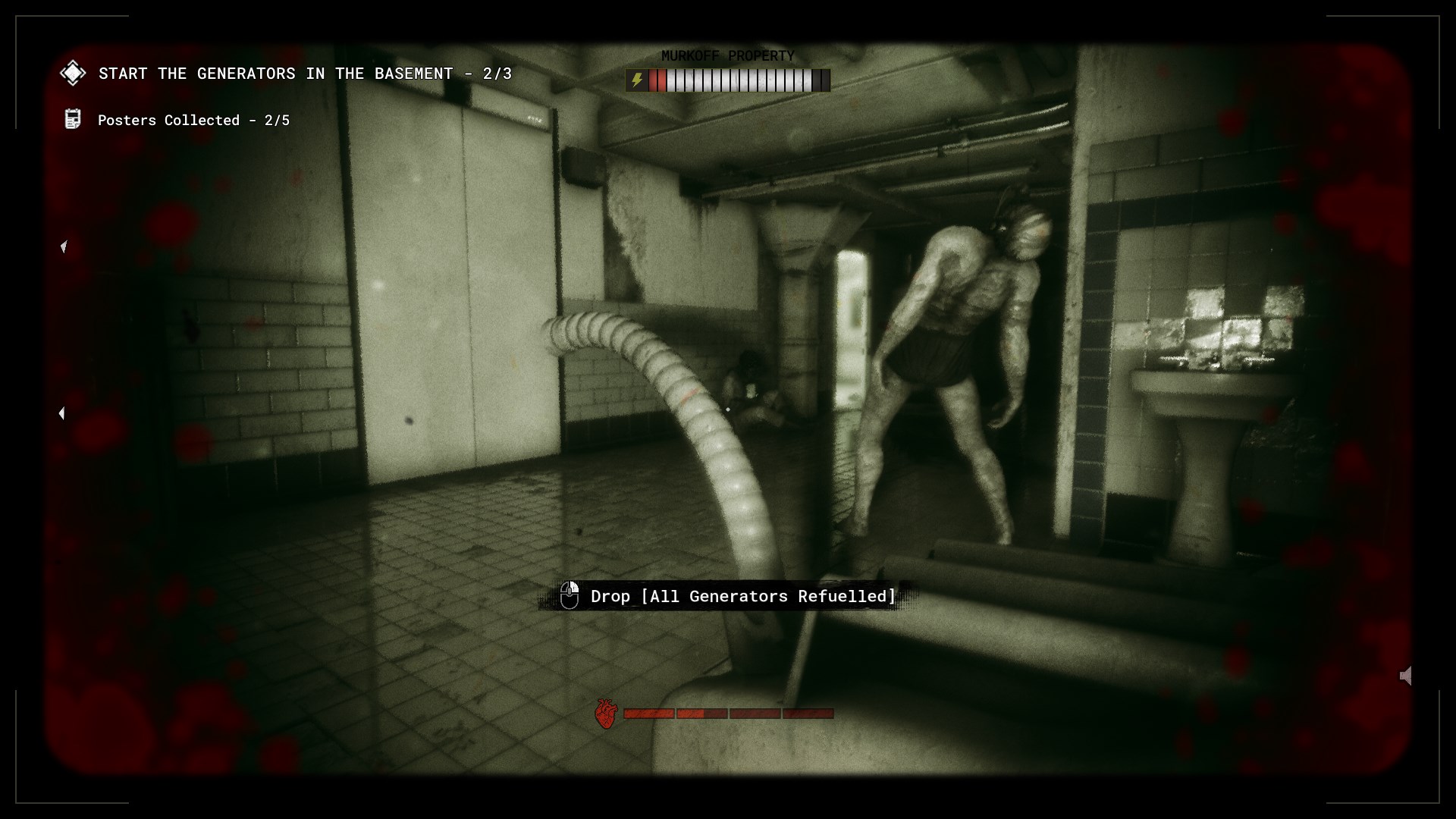

Navigation through these tunnels feels fine, even though your character seems to walk by putting their whole foot down flat like a neanderthal and making as much noise as possible. The confined halls leave little avenue for movement, frequently forcing confrontation with some kind of patrolling patient, the most common of which is the generic Outlast brand mumbling psychos. Cowering under a bed or closet is still the most reliable way to avoid getting your face ripped off, but the ability to throw stunning projectiles & place down nerve gas mines opens up some limited counterplay options for a well-coordinated group.

Collecting keys from the mutilated corpses he leaves in his wake and refilling generators were all but putting me to sleep.

The two most notable encounters I had were with Mother Gooseberry, a self flagellating nun armed with a power drill hidden inside a hand puppet, and the Skinner Man, an emaciated rat-man who hoses you down with madness inducing chemicals. Mother Gooseberry is creepy, sure, but the Skinner Man's hallucinogens require you to find and consume an antidote before the "insanity" affliction overtakes you, which transforms the world around you into one of paranoid delusion. My first time getting poisoned had this god awful 12-foot-tall skeleton man trailing my heels while peering down at me bellowing, a sequence straight out of David Lynch's "Fire Walk With Me".

All of the above comes to a sudden, anti-climactic ending, with you being sucked down a pneumatic tube into one of the saddest social hubs I've ever seen in a game. This is where the Outlast Trials lost me, focusing on co-op missions structured like the heists from Payday 2, complete with gaudy cosmetic options and the ability to decorate your asylum cell. The sudden and jarring transition away from a horror experience that felt so uniquely, personally terrifying was whiplash inducing, with the mysterious, enigmatic therapist in your ear gleefully informing you that the price of freedom is ten special coins, successfully annihilating any lingering tension.

I ultimately found the multiplayer so much less interesting than the opening, awkwardly kiting psychos through dark halls while collecting keycards and refilling generators while my teammates did the same in different corners of the map. At a glance, this sentiment is shared with some series' fans—among the overall "Very Positive" Steam reviews, there's a decent chunk of the Outlast community who feel like Trials fumbles the bag with its multiplayer focus.

The live service model feels at odds with a game that's angling towards something focused, like a politically charged statement about the trauma of growing up an outcast in a paranoid conservative culture. Playing through the second trial, "Kill the Snitch", was a slog both alone and with a well-coordinated group. The rent-a-cop with a shock baton nipping at our heels was no more menacing than the generic psychos, and collecting keys from the mutilated corpses he leaves in his wake and refilling generators were all but putting me to sleep.

That sense of having something peer straight through me only reappeared when I was chastised by my therapist for accepting a "B" grade. "You're settling for good enough? Isn't that what got you here? You get out of the therapy what you put into it." Being the weary target of this overseer's verbal abuse had again stood the hair on my neck straight up. For me, Outlast Trials' narrative strengths are ultimately underserved by it's live service package, but its early access launch has so far been a success: it's been in Steam's top sellers chart for four weeks now.