Just as the UK was recovering from storms Eunice and Franklin, scientists of the UN’s the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a landmark report warning of a future with spiralling weather extremes, fiercer storms, flash flooding and wildfires.

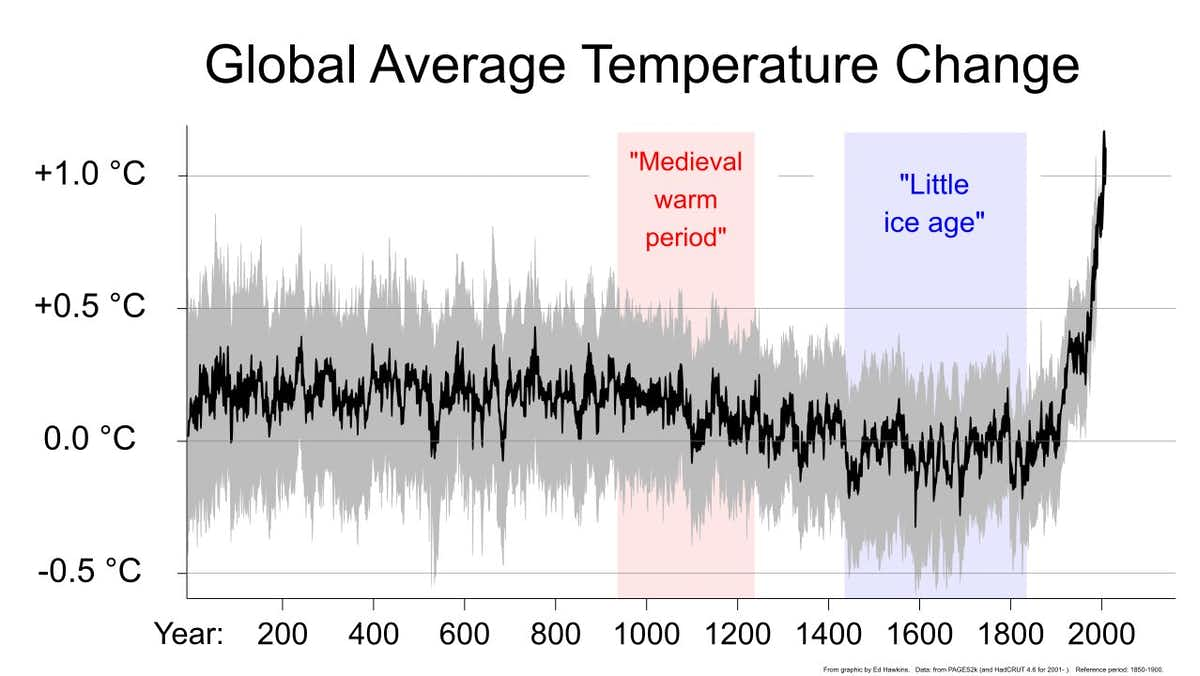

This isn’t the first time that Britain has experienced drastic climate change, however. By the 16th and 17th centuries, northern Europe had left its medieval warm period and was languishing in what is sometimes called the Little Ice Age.

Starting in the early 14th century, average temperatures in the British Isles cooled by 2°C, with similar anomalies recorded across Europe. Much colder winters ensued. Rivers and coastal seas froze, grinding trade and communications to a halt. Crops and livestock withered while downpours spoiled harvests, unleashing widespread hunger and hardship.

This early modern climate crisis was as politically explosive as ours is shaping up to be. There were rebellions, revolutions, wars and plague, as well as the scapegoating of supposed witches suspected of causing the foul weather.

The recent IPCC report predicts dire societal impacts from future climate change, particularly for the 3.6 billion people living in the predominantly poorer countries, which are highly vulnerable to climate change. We can learn a lot about our collective fate today by studying the effects that the last climate crisis had on people.

Fires on the ice

Researchers have offered a range of explanations for the Little Ice Age, from volcanic eruptions to the theory that European destruction of indigenous societies in the Americas caused forests to regrow on abandoned farmland. Others point to the Maunder minimum, a period between 1650 and 1715 when observed sunspots were suddenly scarce.

Local parish relief – a compulsory tax on the wealthier inhabitants of each parish to provide for their poorer neighbours – reduced starvation and saw England suffer fewer deaths than France

Whatever its causes, there is plenty of historical evidence documenting the Little Ice Age. In London, the River Thames froze through 24 winters between 1400 and 1815, with freezes increasing in frequency and severity from the early 17th to the early 18th centuries. People seized the opportunity to hold fairs on the river’s icy surface. The earliest was in 1608, with further notable frost fairs in 1621, 1677 and 1684.

During the “Great Frost” of 1608, people played football, wrestled, danced and skated on the Thames. A pamphlet was printed concerning the “Cold doings in London”. Just over a dozen years later, during the frost of 1621, ice was so thick that teenagers felt confident in burning a gallon of wine upon the Thames, while a woman asked her husband to impregnate her upon the frozen river.

The poet John Taylor wrote of that winter’s frost fair:

There might be seen spiced cakes, and roasted pigs,Beer, ale, tobacco, apples, nuts, and figs,Fires made of charcoals, faggots, and sea-coals,Playing and cozening at the pidgeon holes:Some, for two pots at tables, cards, or dice.

The frost fairs also saw an unlikely mixing of social classes. Between January and mid-February 1684, thousands of people, from King Charles II and the royal family to the lowliest pauper, ventured out to “Freezeland”, as one pamphleteer had christened it. At its height, the fair extended about three miles from London Bridge to Vauxhall. Eyeing a chance to make money and with no ground rent to pay, a number of market stalls sprang up.

Many stalls sold sumptuous food and drink: beer, wine, coffee and brandy; beef, pies, oysters and gingerbread. Entertainment included skating, sledging and dancing, together with football, horse racing, bear baiting and cock throwing. There were puppet plays and peep shows featuring tame monkeys, as well as fire-eating, knife swallowing and a lottery.

But behind this whimsical scene lay upheaval: an early modern cost-of-living crisis. Watermen like Taylor, who ran a river taxi service across the Thames, saw their livelihoods collapse. Many of the stallholders at frost fairs were out-of-work watermen. The price of fuel (predominantly firewood) increased as demand for heating soared. And in Taylor’s “gnashing age of snow and ice”, the shivering poor begged the rich for charity.

Life for London’s poor and newly unemployed was increasingly desperate, with many lacking money to eat and keep warm. The scene was similar across Europe. As Philip IV of Spain toured Catalonia’s barren fields, an associate observed that “hunger is the greatest enemy”.

Contemporaries worried about the social ramifications. The “cryes and teares of the poore, who professe they are almost ready to famish”, wrote John Wildman in 1648, prompted fears that “a sudden confusion would follow”. In 1684, King Charles II of England authorised the bishop of London to collect money for the poor in the city and its suburbs and also donated a sum from the royal treasury.

Local parish relief – a compulsory tax on the wealthier inhabitants of each parish to provide for their poorer neighbours – reduced starvation and saw England suffer fewer deaths than France. Still, the terrible winter of 1684 claimed many lives. Burials were suspended as the ground was too hard to dig. Trees split apart and some preachers interpreted the events as God’s punishment, for which the people must repent.

Lessons from history

Climate change 400 years ago went unheralded by a global body of scientists like the IPCC. Although the scientists of the day, known as natural philosophers, did exchange ideas on the shifting climate, they were forced to reckon with social and economic shocks as a result of temperature changes that they had little capacity to predict.

Superstitions fuelled reprisals among people desperate to blame unfortunate neighbours, like women of low social status, who were prone to accusations of witchcraft in farming communities ruined by crop failures.

Making a virtue of necessity, some who lost their jobs found new ways to make a living. There are those who adapted, notably Dutch navigators who exploited changing wind and weather patterns to establish new international trading routes in their “frigid golden age”.

Most were less fortunate. As one historian notes, the Little Ice Age was experienced as “a sharp deterioration in the overall quality of life”.

History shows that climate change can last centuries and have profound consequences for civilisation. Then, as now, solidarity is the best defence against the unknown.

Ariel Hessayon is a reader in early modern history at Goldsmiths, University of London. Dan Taylor is a lecturer in social and political thought at The Open University. This article first appeared on The Conversation.