With pomp and spiritual fervour pulsing in its narrow alleys and grand temples, the ancient city of Benares has always drawn the curious and the creative. While the Gangetic city’s backdrop of sacred rituals and timeless traditions continues to captivate even today, Ashish Anand, CEO and managing director at DAG, points out how for centuries “the cultural centre has been a muse for artists from India and overseas”.

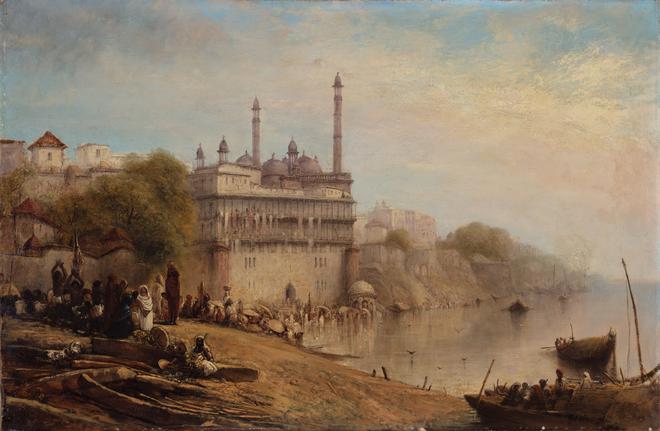

By the late 18th century, spellbinding tales of Benares had started to reach British shores, after landscape painter William Hodges published a series of picturesque views of the city. Other artists followed in his footsteps, most notably the British uncle-nephew duo Thomas and William, to visually document the subcontinent, inspiring a throng of creatives to come over in the next century.

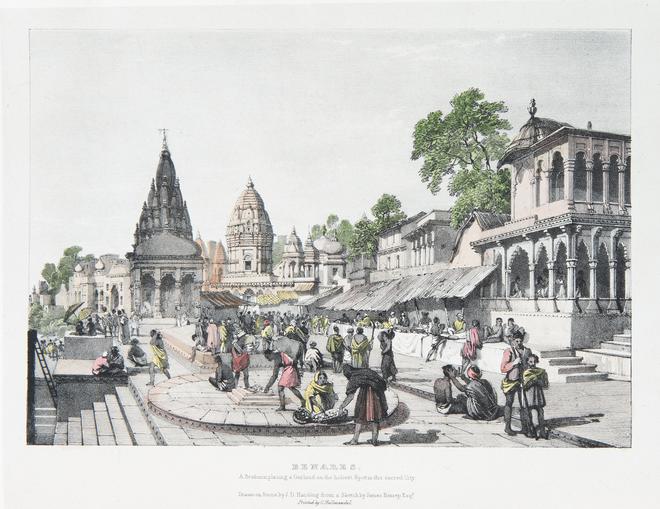

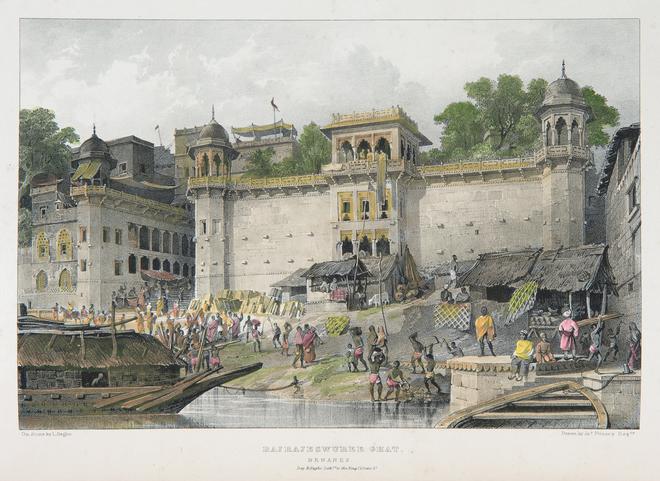

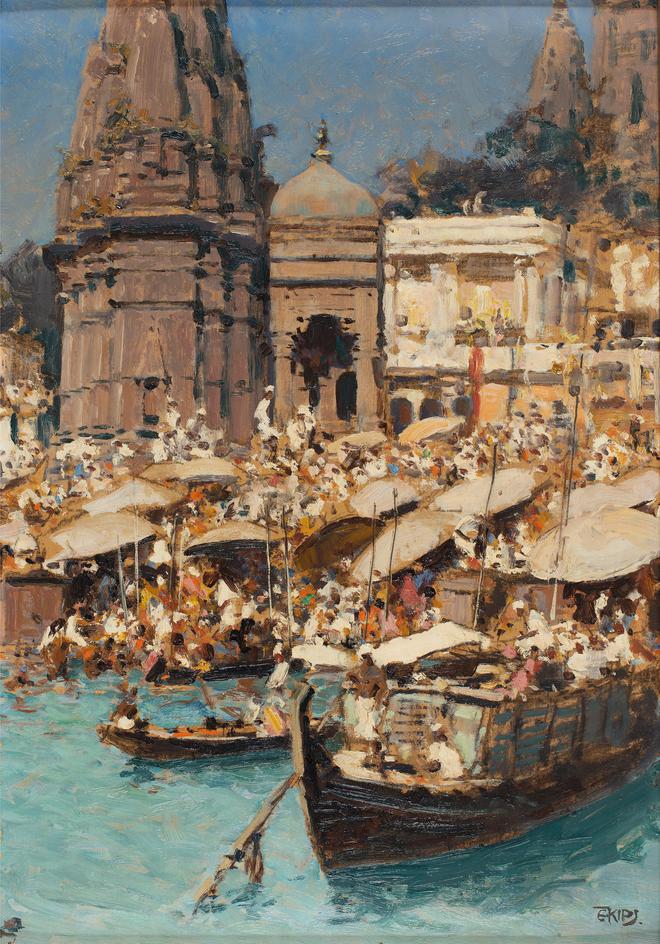

The gallery is showcasing their art through The Orientalists’ Benares, an exhibition of works by foreign artists in the 19th and early-20th centuries, specially curated for the ongoing Mumbai Gallery Weekend. Comprising 15 works by artists Thomas Daniell, Marius Bauer, Ludwig Hans Fischer, Erich Kips, Richard Robert Drabble, C. J. Robinson, Alexander Scott, Yoshida Hiroshi, James Prinsep and Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès, “it is a curtain raiser for a much larger exhibition on Benares slated for later this year that includes a wide gamut of Indian artists across different periods and mediums”, Anand adds.

India and Orientalism

A writer and lecturer on Indian history and architecture, Giles Tillotson, the senior vice president of exhibitions at DAG, establishes a simple meaning of the term ‘orientalist’ — as a western artist who made Asian subjects the main theme of their work. However, after Edward W. Said wrote the book Orientalism in 1978, Tillotson argues that the term is inextricably tied to the imperialist societies who produced it, which makes a lot of orientalist work inherently political and servile to power.

“At DAG, we’re using the term in both senses. We pick up these paintings in Europe and bring them back to India because we believe they’re part of the history of Indian art,” he says. “While there are several facets that are romanticised, there are many buildings in the sceneries that [are true representations but] no longer exist today,” he says.

Interestingly, in the 1950s, when the Archaeological Survey of India restored a mediaeval temple in the Rohtas District in Bihar, they used the Daniells’ view of it as their guide to restoration. Their representation of the Qutub Minar is the only formal documentation ever recorded, which showcases the original cupola at its top that was destroyed by lightning in 1803.

Each artist came to Benares with their own preconceived ideas. “Hodges said it was fascinating to see people whose customs had not changed for over 3,000 years,” reveals Tillotson. “So, when the Daniells visited, they believed they’d see a kind of living antiquity. Obviously, that was completely wrong. Benaras is a constantly changing city, always being developed — even back then.”

Prinsep’s book

Framing a holy city

The way each artist composed a picture was ruled by the framing of English art. “When you look at the pictures, there are very few people in them. There may be a few figures for scale or to animate the space, but it’s not bustling or teeming with folk. And it was not like that, even at the time,” says Tillotson, referencing William Daniell’s journal, where he often complains about the number of pilgrims around the sacred sites, making it difficult for him to get on with his work. “They’d sit down to make a sketch, and suddenly there’d be a swarm of people around them. But when you see the pictures, the people have disappeared. The artist wanted this image of serenity.”

Tillotson reveals how Edward Lear, an author and landscape painter, had visited the India Office Library in England to look at the work by the Daniells as a visual stimulus before visiting India in the 19th century. “When he got to Benares, he couldn’t believe it was the same place. He remembered the views by the Daniells being sad and solemn when in actuality, it was a bright, brilliant, noisy place.”

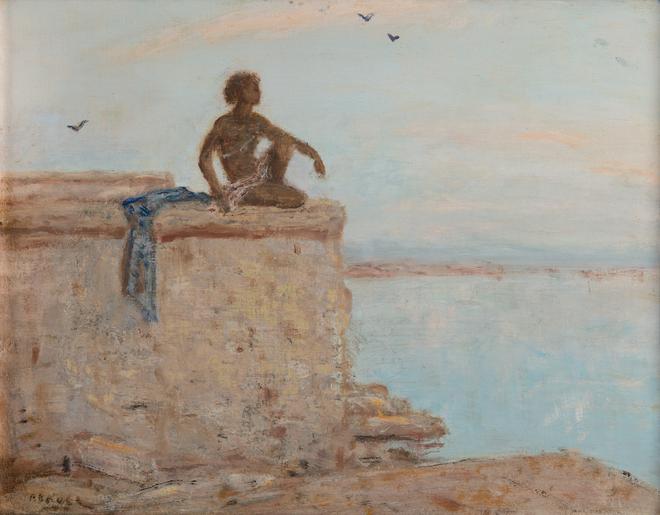

While the early period is more about exploration — to showcase this world to the western audience — by the end of the 19th century, these were quickly becoming clichés. It was around this time that one saw the introduction of photography, most notably from British photographer Samuel Bourne who set up his photographic studio, Bourne & Shepherd, in India. It brings a turning point in the exhibition where the artists, too, begin to echo a more creative interaction with the city. This vividly comes to life in Belgian painter Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès’ oil on wood, titled Street Scene, Benares, where a confetti of celebration and pageantry shimmers in the city’s alleyways in a dream-like abstraction.

“The point to take away from this [The Orientalists’ Benares] is that the foreign gaze is not fixed,” says Tillotson, suggesting, “The idea that colonialism or the imperial gaze was monolithic, unchanged and unshifting — being an outsider’s misinterpretation — is not entirely true. It was an ever-changing and evolving comparison of India.”

‘The Orientalists’ Benares’ is on display at DAG 1, The Taj Mahal Palace, Mumbai, till January 14.

The writer and creative consultant is based in Mumbai.