Working from an old winery compound in Deidesheim, the Rhineland-Palatinate vineyard region of Germany, it’s safe to say that Jens Ritter is at the forefront of 21st-century bass design.

In 2016 he released the Cora model, co-designed by Prince bassist Josh Dunham, which boasted tuning pegs, bridge hardware and control knobs that were all coated in distressed 24k gold.

Grateful Dead bassist Phil Lesh also made a custom order back in 2008, the result being his Jupiter ‘Eye of Horus’ bass. Lesh’s 6-string bass guitar featured solid silver inlays, blue front and side LEDs, custom electronics, Ritter’s Quattrobucker pickup and a futura frosted finish.

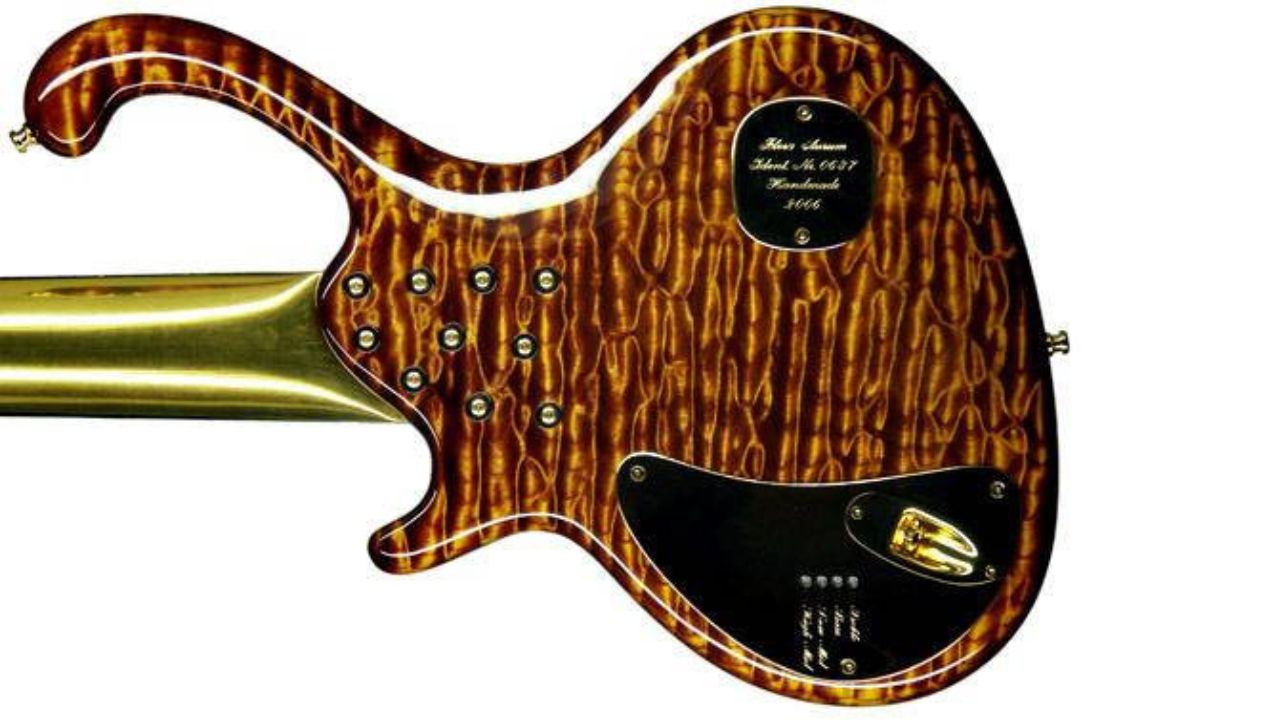

Jens Ritter's basses are among the most beautiful, intricate, and expensive works of playable art, but it's safe to say he topped himself with the Ritter Royal Flora Aurum back in 2007: the body was carved from an extremely rare, solid piece of quilted maple. Its bridge, tuners, and knobs are hand-cast solid gold. Two flawless diamonds – totalling 3.3 carats – adorn the volume and tone knobs.

Then there's the gold leaf covering the back of the neck and headstock, the tiny green-diamond knob position markers, and the ebony fingerboard's Renaissance-inspired solid-gold flower inlay – each leaf decorated with a platinum-set black diamond. And the nut? Carved from 10,000-year-old Siberian mammoth-tusk ivory.

Unlike most Ritter basses, which start around $6,000, the Flora Aurum – created to mark the company's tenth anniversary – was priced at $100,000, well above the most high-priced Ritter Royal series, which has basses starting around $15,000.

Still, $100,000 could perhaps be considered a modest price tag, given the 15-month development and construction process Jens Ritter required to perfect the instrument's various facets.

The following interview from the Bass Player archives took place in 2007.

Why did you create the Flora Aurum?

“I wanted to do something special for my tenth anniversary, and I had a customer who wanted me to build the most expensive bass of all time. It's not just an instrument; it's a statement, a symbol of the development of the bass.

“20 years ago bass was always in the background – the second choice to play after guitar. But in an interesting development, more and more people are in front playing bass guitar, and bass players are becoming more self-confident. Similarly, more development is happening in bass design than with guitar.”

Were there aspects of working on this instrument that helped you grow as a bass builder?

“For the first time in my life I used a one-piece quilted maple body of this quality. It's a very nice, highly quilted piece I got it two years ago by chance at a trade show, and saved it for my 10th anniversary instrument.”

“Also, it takes a lot of knowledge to work with gold, but it was really interesting to learn to work with the material. The technique I used to apply the gold in the inlays is an antique style from the Middle Ages. Working with the solid gold was a process; we cast the bridge several times until we got the result we wanted.”

There's even gold on the pickup covers.

“Gold is not magnetic, so you can cover the whole pickup and not have any effect on the performance or tone.”

Do you expect this instrument will actually be played, or just cherished by a collector?

“You may not believe this, but nearly all of the instruments I build are played onstage. Even the guys who are buying $30,000 instruments use them onstage. The customer who is interested in this bass is a musician – not a professional, but he plays live.”

What else have you been doing to perfect your craft?

“I studied Stradivarius violin-making, and I drove down to Cremona, Italy, to meet with Professor Andrea Mosconi, the keykeeper of the Stradivari area. When he played a Stradivarius for me, I started to cry. It's an unbelievable energy.”

“Like those of us working on bass guitars now, the violin was fairly young when Antonio Stradivari worked; it was only about 70 years old. And he found his perfect setup quickly: flame-maple sides and back, spruce top, and ebony fingerboard. It was not a common setup in those days, but today it's common because everybody wants to copy Stradivari.

“Afterward, he was thinking about how he could improve his instrument, but felt he had reached a limit and couldn't go far from his design. That's when he came across a psychological factor. He started doing custom inlays of faces, naked girls – things that were totally punk-rock at that time – and people began to appreciate the beauty of the instrument.

“But it doesn't have to be inlays, gold, or diamonds; sometimes it's about dirt or character. For example, I built a very simple mahogany bass for a customer who put his baby daughter's footprints on it before l applied the finish coat, and that instrument is especially meaningful to him.”

“The psychological factor is about what would make the most unbelievable instrument for each person. Finding the perfect psychological factor for each customer is the goal.”