When Allison Simpson's dad returned from Vietnam to a small country town, there was no support for his mental health problems.

Decades later, Ms Simpson, 50, has just finished a novel treatment to address her own depression.

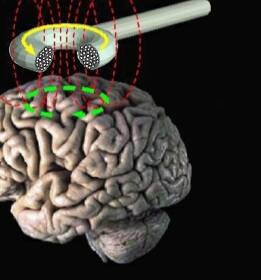

Brainwaves

Ms Simpson has had transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), in which magnetic pulses stimulate certain areas of the brain through a coil.

People will usually have regular sessions over a period of several weeks.

Ms Simpson initially had TMS to treat headaches, before taking on additional sessions for depression.

She would travel to Murrumbateman, half an hour each way, for three-minute sessions.

"It took about two-and-a-half weeks. I just started to feel a little bit more positive and a lot better in myself," Ms Simpson said.

There are Medicare rebates available for between 35 to 50 TMS sessions.

Paul Fitzgerald, a psychiatrist and the head of ANU's combined school of medicine and psychology, launched his book Curing Stubborn Depression on Wednesday.

He said one-third of people treated for depression don't get better with the usual treatments.

"There is ... a very large proportion of people who [have] significant disabling depression where our standard treatments just doesn't do all that much good," Dr Fitzgerald said.

He said depression was a growing issue for young people, and was more likely to affect girls and women.

"Unless we get very much better treatment, they're going to carry impairment and disability and challenges with dealing with those problems through their lives," Dr Fitzgerald said.

"We do have hope and it is my belief that regardless of the person's depression that there is a way for us to make them better."

While relatively unknown, treatments like TSM and esketamine have decades of experimentation behind them, said Rodney Blanch, psychiatrist at the Murrumbateman Specialist Centre.

"We have to take the evidence ... and I have to apply it to you as an individual. It's not about, 'This drug company took me out for lunch, and so I'm now giving you their drug'," he said.

Esketamine

Esketamine, made from ketamine, is a hallucinogen used as an anaesthetic and quick-release anti-depressant.

Dr Fitzgerald said one client, a former police officer with post-traumatic stress disorder, failed to progress after trying more than 12 different medications and various psychological treatments.

"I consistently felt worthless, hopeless, without confidence and less of a man," the patient said through a statement.

The former policeman has progressed after taking esketamine through a puffer.

"I didn't think I was going to be able to make this progress. I didn't think I would be happy and as appreciative as I am now," he said.

"I still have done periods where the old demons pop up, but I'm much better able to cope with and manage them."

Hallucinogens

Australia is also pioneering the use of drugs like MDMA and psilocybin for therapeutic uses, Dr Fitzgerald said.

"Australia is very much on the leading edge now of the implementation and expansion of services around what's generically known as psychedelic assisted psychotherapy," he said.

Dr Fitzgerald is leading several studies at the ANU into the impact of MDMA and psilocybin on the brain.

A recent drug and alcohol survey found an increase in the use of hallucinogens and ketamine from 2019 to 2022-23.

Media coverage of the use of these drugs in therapy might be behind this, senior lecturer in addiction at Edith Cowan University, Dr Stephen Bright, said.

"However, without the support of trained professionals, Australians who attempt to treat their mental illness using illicit drugs could unwittingly make their mental health worse," he said.