Standing under the night skies in North America pointing out stars with Arabic names and constellations that fit Greek mythology — many derived from Babylonian and Egyptian star knowledge — seems rather odd. After all, indigenous people in North America have been stargazing for many thousands of years.

Full moon names like the 'Hunter's Moon' and 'Wolf Moon' might be familiar to many as ways of various tribes to keep track of the seasons for farming, hunting and gathering, but since there are hundreds of different indigenous tribes in North America, both contemporary and historical, creating a list of official names for anything is perhaps little more than cherry-picking.

Related: What you can see in tonight's night sky [maps]

Revival of Indigenous astronomy

Indigenous interpretations of the night sky in North America are not only hugely varied across the region, but these oral traditions have suffered over time (though there are plenty of lost constellations in Western astronomy, too).

However, in recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in, and scholarly work on, indigenous astronomy, most notably the Native Skywatcher's project. Led by native Annette S. Lee, Professor of Astronomy & Physics at St. Cloud State University (SCSU), it seeks to revitalize indigenous astronomy through the resurrection of star maps unique to communities including Ojibwe, D/Lakota and Cree.

Other resources include Navajo Skies led by Nancy C. Maryboy of the Indigenous Education Institute (IEI) and the free and open-source planetarium software Stellarium, which integrates indigenous sky cultures for the Navajo, Dakota and Ojibwe cultures.

It merely scratches the surface, but here's a tiny sample of just some of the star shapes from indigenous communities in North America to look for in the night sky:

First Revolving Male, First Revolving Female and Central Fire

Perhaps the most well-known indigenous mythology of the night sky relates to the stars of the north.

For the Navajo and some other indigenous cultures the Big Dipper, Cassiopeia and — between the two — Polaris, the North Star, are thought of as one huge constellation. The Big Dipper is called Náhookòs Bi'kà' (First Revolving Male), Cassiopeia is Náhookòs Bi'áád (First Revolving Female) and Polaris is Náhookòs Bikò' (the Central Fire). This depiction of a husband and wife around a hearth works well because both constellations are circumpolar so revolve around Polaris.

However, the Dakota culture sees the Big Dipper as Manka/Maka (Skunk) and its bowl as both To Win (Blue Woman) and Tun Win (Birth Woman). The Ojibwe interpret it as Ojiig (Fisher).

The Wintermaker

The three bright stars that make up the famous Orion's Belt are not only spectacularly aligned but they're surrounded by many other bright stars.

Many indigenous cultures see Orion as a male figure, just as Greek mythology does — including the Navajo for whom the stars are Átsé Ets'ózí (First Slim One). In Ojibwe culture, the stars Procyon in Canis Minor and Aldebaran in Taurus are added to create a vast figure — Biboonkeonini (The Wintermaker) — so-called because the stars of Orion are best seen in December and the winter months. The Ojibwe and other tribes only tell stories during the winter months when the Wintermaker was visible.

Curly Tail, The Great Panther

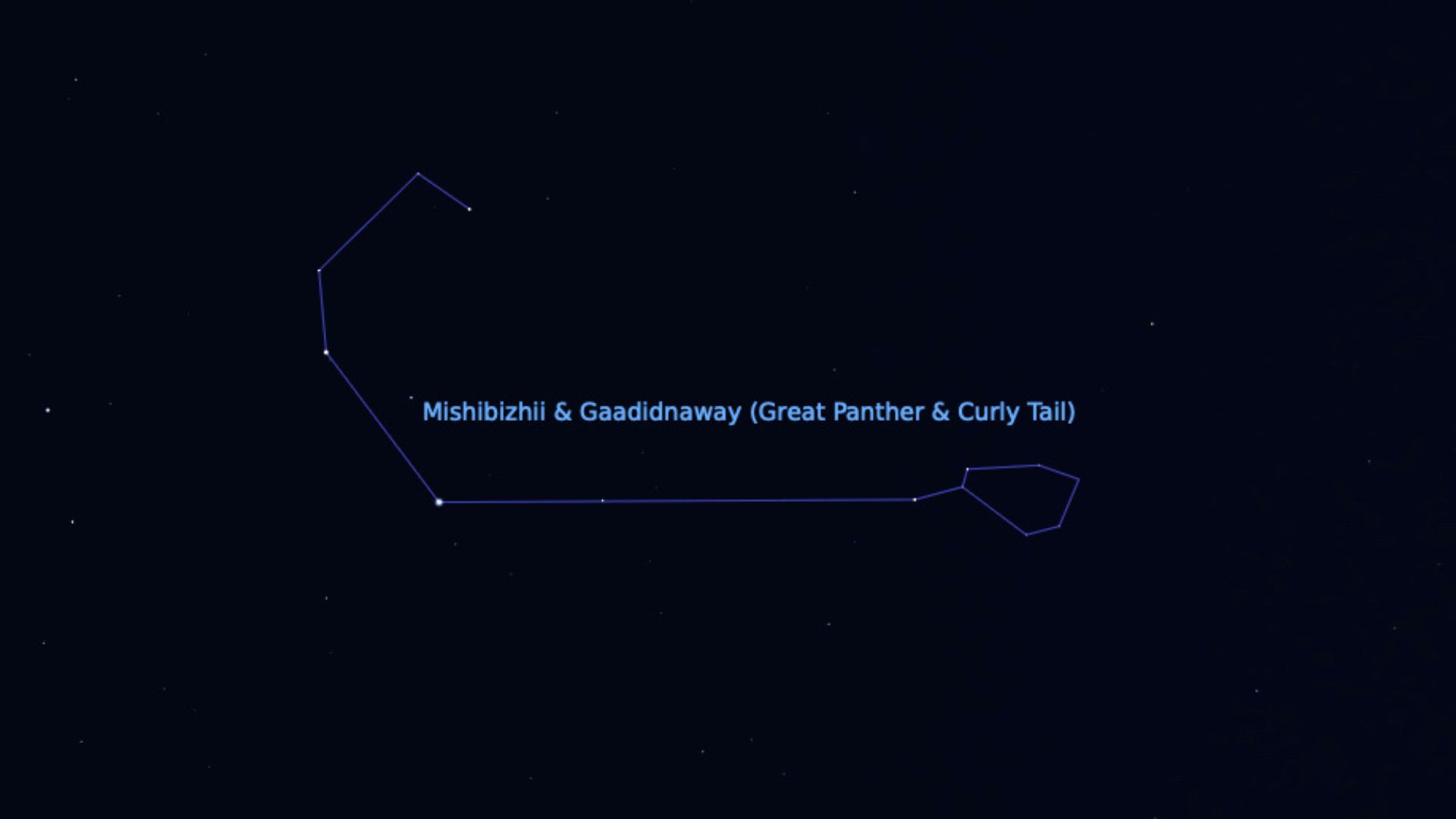

The Ojibwe culture sees Gaadidnaway, Mishi bizhiw (Curly Tail, The Great Panther) while the Greeks saw Leo, the lion.

It might seem like a similar interpretation, but the two shapes are distinct. The Sickle of Leo, the lion's head — a backward-looking question mark with bright star Regulus as its dot — is instead interpreted by the Anishinabe and Ojibwe cultures as the curly tail of a panther which has its head in the faint stars of the Hydra constellation. In Ojibwe culture, there are four main constellations — The Wintermaker (winter), Curly Tail (spring), Nanaboujou (the stars of Scorpio in summer) and Moose (the stars of Pegasus in fall).

Hole in the Sky

One open cluster of stars, many names. Representing the Seven Sisters in Greek mythology and found in the constellation Taurus, the stars of Pleiades (M45) have dozens of different indigenous names.

Ojibwe culture calls it the Bugonagiizhig (Hole in the Sky) and it tends to be thought of as a kind of spiritual doorway between Earth and sky while in Dakota, Lakota and Nakota culture it's Wiçinyanna Sakowin/Wiçincala Sakowin (Seven Girls) and the head of the buffalo-like Tayamni constellation. Both cultures also call it Madoo'asinik (Sweating Stones).

The Navajo call it Dilyéhé and associate it with the planting season. That's because it disappears from the night sky in spring — when seeds need planting — and reappears at harvest time in fall. The other naked-eye open cluster in the northern sky, the Beehive Cluster (M44) in Cancer, is in Navajo culture called Tsetah Dibé (Mountain Sheep).

First Big One and Man With Feet Apart

Look south after dark in summer from the northern hemisphere and you'll see the stars of Sagittarius, Scorpius, Virgo and Corvus, but in Navajo sky lore there are two figures. Átsé Etsoh (First Big One) sees the upper part of Scorpius as a torso of an elder with a walking stick and a basket. To his left beyond the bright star Spica in Virgo, amid the stars of Corvus, is another figure called Hastiin Sik'aí'ií (Man with Feet Apart).

The Salamander, The Crane and The Skeleton Bird

The Greek constellation of Cygnus, the swan, is sometimes read backward and called the Northern Cross, but in Dakota culture, this same shape — obvious to stargazers across the world during summers throughout history — is called Ahdeska/Agleska (Salamander). To the Ojibwe, it's Ajiijaak (The Crane) — one of the leaders in the Ojibwe clan system — and Bineshi Okanin (The Skeleton Bird).

The Sacred Hoop

Step outside in January and look south and you'll see the most incredible and enormous shape in the stars around the constellation of Orion.

There are seven bright blue stars that form a hexagon shape around Orion and the red supergiant star Betelgeuse. The Dakota culture has a variety of names including Çan Hd/Gleska Wakan (Sacred Loop), Inipi/Initipi (Sweat Lodge) and Ki Inyanka Ocanku (Racetrack).

The pattern is very similar to the Winter Circle or Winter Loop, but with one key difference — instead of Aldebaran as a constituent star, the Pleiades is used.

Additional resources

If you're curious about Native American constellations and want to learn more of the star lore behind them then be sure to read Nancy C. Maryboy's Navajo Skies, the Native Skywatcher's project, Stars of the First People: Native American Star Myths and Constellations and They Dance in the Sky: Native American Star Myths.

Bibliography

A collection of Curricular for the STARLAB Navajo Skies Cylinder, Nancy C. Maryboy, Ph.D. of the Indigenous Education Institue (IEI) https://www.raritanval.edu/sites/default/files/aa_PDF%20Files/6.x%20Community%20Resources/6.4.5_SD.10.NavajoSkies.pdf

Home. Stellarium Labs. (n.d.). https://stellarium-labs.com/

King, B. (2014, November 12). Make way for the Wintermaker. Sky & Telescope. https://skyandtelescope.org/observing/make-way-wintermaker11122014bk/

LeMay, K. (2014, August 13). “native skywatchers” revives Indigenous Star Knowledge. Lake Superior Magazine. https://www.lakesuperior.com/the-lake/natural-world/native-skywatchers-revives-traditional-constellations/

The lost constellations. John C. Barentine’s Personal Website. (n.d.). https://www.johncbarentine.com/the-lost-constellations.html

Minnesota Skies: September 2020. Bell Museum. (2020, August 28). https://www.bellmuseum.umn.edu/blog/minnesota-skies-sept-2020/

Native skywatchers - resources. Native skywatchers. (n.d.). https://www.nativeskywatchers.com/resources.html

Ominika, W. (2020, March 18). Ojibwe astronomy. Great Lakes Guide. https://greatlakes.guide/ideas/ojibwe-astronomy

Star Lore. Myths about the Constellation Orion Part 1. (n.d.). http://judy-volker.com/StarLore/Myths/Orion1.html