I have to tell you something,” says Dorothy Stratten in the new Disney Plus series Welcome to Chippendales. “Women get horny.” What happened next was the invention of the first all-male strip club, launched in 1979 and aimed exclusively at female consumers. Think greased-up abs and baby oil. Tear-away trousers and bedazzled G-strings. Chippendales was the blueprint.

Thanks to the apparently shocking revelation that women enjoy sex, and the fact that women’s pockets were getting deeper as they found economic independence in the Eighties, Chippendales was a roaring success. Fireman uniforms? Women’s jaws would hit the floor. Men dry-humping the air in police garb? They’d scream for more. For the first time in erotic history, women were the ones throwing money at sexualised bodies.

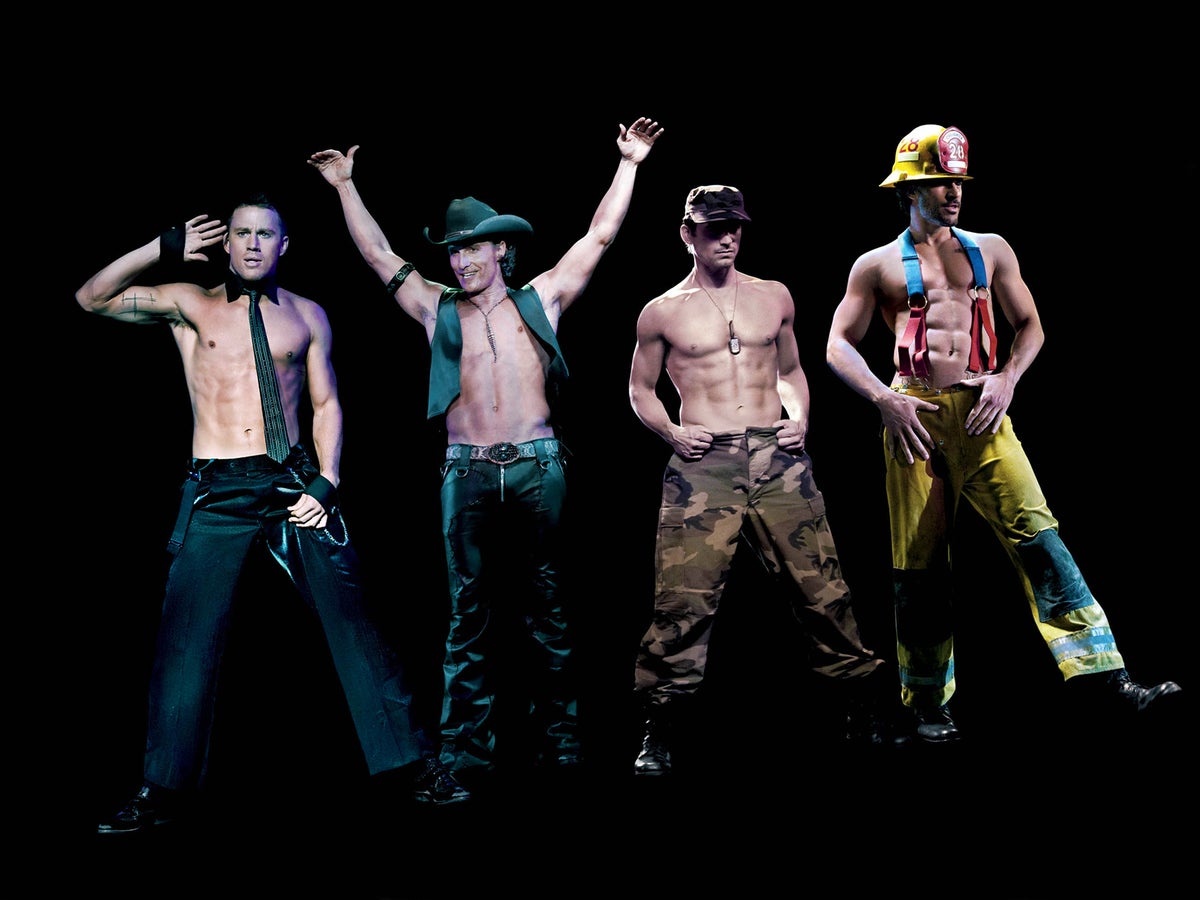

Four decades later, and men’s exotic dancing has shimmied into far cooler terrain. You can thank Channing Tatum for that, with his franchise of Magic Mike films arriving in 2012, loosely inspired by Tatum’s real-life eight-month stint as a stripper at the age of 19. While director Steven Soderbergh initially planned for the franchise to expose a murky strip-club world of drug deals and exploitation, the films became far more a celebration of friendship and male sexuality. Audiences were captivated, with cinemas engulfed by groups of straight women and gay men eager to witness the likes of Tatum and Matthew McConaughey wearing next to nothing but neatly knotted ties and glittery undies. Magic Mike and its 2015 sequel Magic Mike XXL grossed nearly $300m (£245m) worldwide, and another sequel – Magic Mike’s Last Dance – is due for release in February.

Billy Blue Eyes, the founder of the all-male “sexy circus” Forbidden Nights, remembers the beginnings of Magic Mike mania well. “Before Magic Mike, the industry was really stagnant,” he tells me. He began dancing, like Tatum, at the age of 19. He’s now 35. “There was the Chippendales, Thunder from Down Under and Dreamboys, but none of the older concepts had evolved from the banana and baby oil routines. When Magic Mike came out, we were selling nearly 600 tickets per week. People had the bug. Women wanted more.”

These days, the term “stripper” has been ditched for “dancer”, the former seen as derogatory and slightly undermining of the sheer physical skill involved in the practice. While there’s still, admittedly, a fair amount of baby oil involved, men’s burlesque dancing is now more associated with impressively intricate choreography than schlongs-out gyration.

The Chippendales image of long-haired, thong-wearing men has been left in the Eighties, says Jordan Darrell, the choreographer and creative director of Dreamboys. The company was founded in 1986, with Darrell joining “the stripping world” eight years ago. By that point, the industry had shifted. “It’s not just easy guys greasing themselves up,” he tells me. “We’ve moved on from that.” While those walking through the doors of male strip clubs are widely assumed to be raucous mobs of women celebrating hen dos or cheering up the recently dumped, Darrell says the Dreamboys audience ranges all the way from 18 to 100. “We had one lady celebrate her 101st birthday at our show,” he says. “She loved it. It’s really for everyone. We have straight couples attend, families and groups of friends.”

A lot of people presume, because we’re guys, that we will handle [any] situation. But there’s only about eight of us on stage in an auditorium of 1,000 people

In 2019, Tatum launched Magic Mike Live, an IRL theatrical experience spun off from the franchise, which sees dancers inviting women on stage and slithering all over them. Darrell, however, is adamant that the industry has today created a safe environment for audience members. “It’s about being somewhere where you’re comfortable enough to just let your hair down, scream, and be kind of naughty and obscene for a couple of hours,” he says. “That’s what we’re providing.”

Unlike Magic Mike Live, the Dreamboys cast performs fully nude. But Darrell says that punters do seem to appreciate the technical work that goes into the show. “People often compliment us on the production and our performance skills,” he says. He’s worked as a professional dancer in popular West End shows like The Bodyguard and Thriller, and danced for the likes of Take That and Jess Glynne, but he says he’s found more agency as a performer in his newer gig than anything he’s done before. “I’ve danced behind a lot of artists,” he explains. “But in Dreamboys, we are the artists. We actually have creative control.”

There are still, however, misconceptions about the shows. “The worst thing is how many boyfriends and husbands don’t want their partners visiting,” Billy says. “In reality, they could come along, too.” Amid growing conversations about consent post-#MeToo, the mainstream men’s burlesque world also covertly incorporates the language of consent into routines. Dancers in these shows will discreetly ask audience members for permission before making a choreographed move. While it may look like a dancer is seductively whispering in an audience member’s ear when they pull them up on stage, they’re actually asking them for permission to touch them.

In fact, it’s the dancers themselves who are left acutely vulnerable in these situations, with fans sometimes crossing the line. Attend any licensed erotic dance show with female performers and you’ll often be confronted by strict no-touching rules, as well as a brigade of security guards on alert to protect the dancers. At Magic Mike Live, Forbidden Nights and Dreamboys – all mainstream shows – the audience is allowed to touch and feel. It’s something reflected in Welcome to the Chippendales, too. In one scene, dancer Otis (Quentin Plair) is left distressed after he’s groped and forced to kiss members of the audience. When I describe the scene to Billy, it sounds all too familiar.

“We get people running their nails down our back, jumping on stage, touching us intimately,” he says. “During one show, one of our boys had to leave the stage because someone in the audience scratched him so badly. Ask anyone in the industry and they will say that nail-scratching is the worst thing. I’m not sure why people think that’s sexy.”

Darrell, similarly, recalls having more than 50 audience members surge the stage when the Dreamboys reopened post-Covid. “It was very daunting,” he says. Though he’s adamant things are improving, he hints that the gender stereotypes at play might have something to do with it. “A lot of people presume, because we’re guys, that we will handle a situation like that. But in reality, there’s only about eight of us on stage in an auditorium of 1,000 people.”

When I attended Magic Mike Live a few years ago, I found there to be something unsettling about the level of trust given to the audience when we were invited to touch the dancers. There’s also something bizarre about the heteronormative, sexually conventional nature of strip shows in general. It feels built on slightly prehistoric assumptions about what women find erotic – just as not all men wish to be straddled by women with huge breasts, not all women wish to be ground up against by a man with a 12-pack.

Billy tells me he’s noticed it as well. “We are currently looking into designing shows for gay, bisexual, and sexually open people,” he tells me. “I’m surprised it hasn’t happened sooner, because I think gay guys can get put off coming to the shows when it’s catered predominantly towards straight women. Everyone has different tastes, and I think the industry really needs to catch up with that.”

While Chippendales will be remembered as one of the first clubs that sought to both quench and monetise womens’ appetite for raunchy entertainment, it leaves behind a strange legacy – one that only sometimes seems to acknowledge evolving ideas about lust, desire and consent. Speak to those in the exotic dance world, though, and it’s admirable that many seem eager to get with the times. I just hope they ditch those fireman outfits as they go.

‘Welcome to Chippendales’ is out now on Disney Plus in the UK and Hulu in the US