Wendy Froud was primed to create some of cinema’s most magical creatures from an early age. You might even say it was destiny.

“I was named after Wendy in Peter Pan,” Froud tells Inverse. “I grew up believing in fairies, and my mother made that a part of my childhood.”

You might not recognize the name Wendy Froud (née Midener), but in the practical effects world, she’s a legend. Renowned in film and television as a pioneer in puppetry, Froud was sought out by directors like Jim Henson early in her career and created countless iconic TV and movie creatures. Yet she remains an obscure name rarely credited accurately on film sites or IMDb.

Despite what history may tell you, this long-haired, aetherial puppeteer with a Fleetwood Mac aesthetic played a crucial role in the birth of animatronics, providing the puppet design for groundbreaking films The Empire Strikes Back, The Dark Crystal, and Labyrinth. A Froud original can go for $4,500, and her work even earned her one of pop culture’s greatest monikers: the Mother of Yoda.

But in 1988, at the height of Froud’s career, the woman who made some of the world’s most beloved puppets seemingly vanished. Uncovering the truth behind her rise and fall would require tracking down a woman who’s stayed out of the public eye for 30 years, but her story says more about the hidden history of practical effects than it does about one woman’s time in Hollywood.

Early Days

Born in 1954 to a pair of artists living in Detroit, Michigan, Wendy’s mother read her fairy tales, J.R.R. Tolkein, and C. S. Lewis as a child.

“We made fairy houses in the garden,” Froud says.

By age five, she was making her own dolls using household items: Fauns, satyrs, centaurs, and fairies. Years later, she’d channel that love of the mythic into similar creatures for Dark Crystal and Labyrinth, but first, she’d have to reconcile her love for the fantastic with 1970s pop culture.

As a young woman attending Detroit’s College for Creative Studies, she encountered David Bowie for the first time.

“We saw Bowie in concert a few times, and we, of course, absolutely loved it,” Froud says. “I never in my life thought I would be working with him one day. Same with Star Wars, which I saw back in Detroit and loved. I never thought I would be working on a movie, let alone that one. But part of that is just saying yes to things.”

After graduating in 1976, a 24-year-old Wendy moved to New York City with friends. In the late 1970s, the bankrupt city was a magnet for artists and theater types, and Wendy sold her dolls at local galleries. Cheryl Henson, a puppeteer, creature designer, and the second child of Jim Henson, would meet Wendy while building and creating puppets with her father.

The Henson Workshop

Cheryl Henson has a glorious mane of long, thick hair and a voice that belongs on a podcast. When it comes to puppetry, Henson history, and filmmaking, she’s an encyclopedia and natural storyteller. Henson, who’d taken a year off between high school and college to build puppets for The Dark Crystal and the last season of The Muppet Show, sees Froud as a unique talent.

“Wendy’s work has always been consistently her work,” Henson says. “It doesn’t change with fads or bend to trends, it’s unique. And her style was absolutely perfect for The Dark Crystal.”

“Months were spent creating these environmental creatures... It’s not economical.”

Henson recalls that art director Michael K. Frith saw Froud’s work when she was showing her dolls at a New York City gallery. That chance encounter would change the course of Wendy’s life.

Frith bought several of the dolls as Christmas presents for his boss, who was so enthralled by them that he encouraged Frith to recruit Froud to help develop characters for his new fantasy film. She said yes. And so, Froud’s first job out of art school was with famed puppeteer Jim Henson on the movie The Dark Crystal.

During this period, the Henson workshop in New York created hundreds of characters for Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, both of which Froud worked on. If not for Henson, Wendy believes she wouldn’t have pursued a career in film at all.

“It wouldn’t have crossed my mind that I could,” she says.

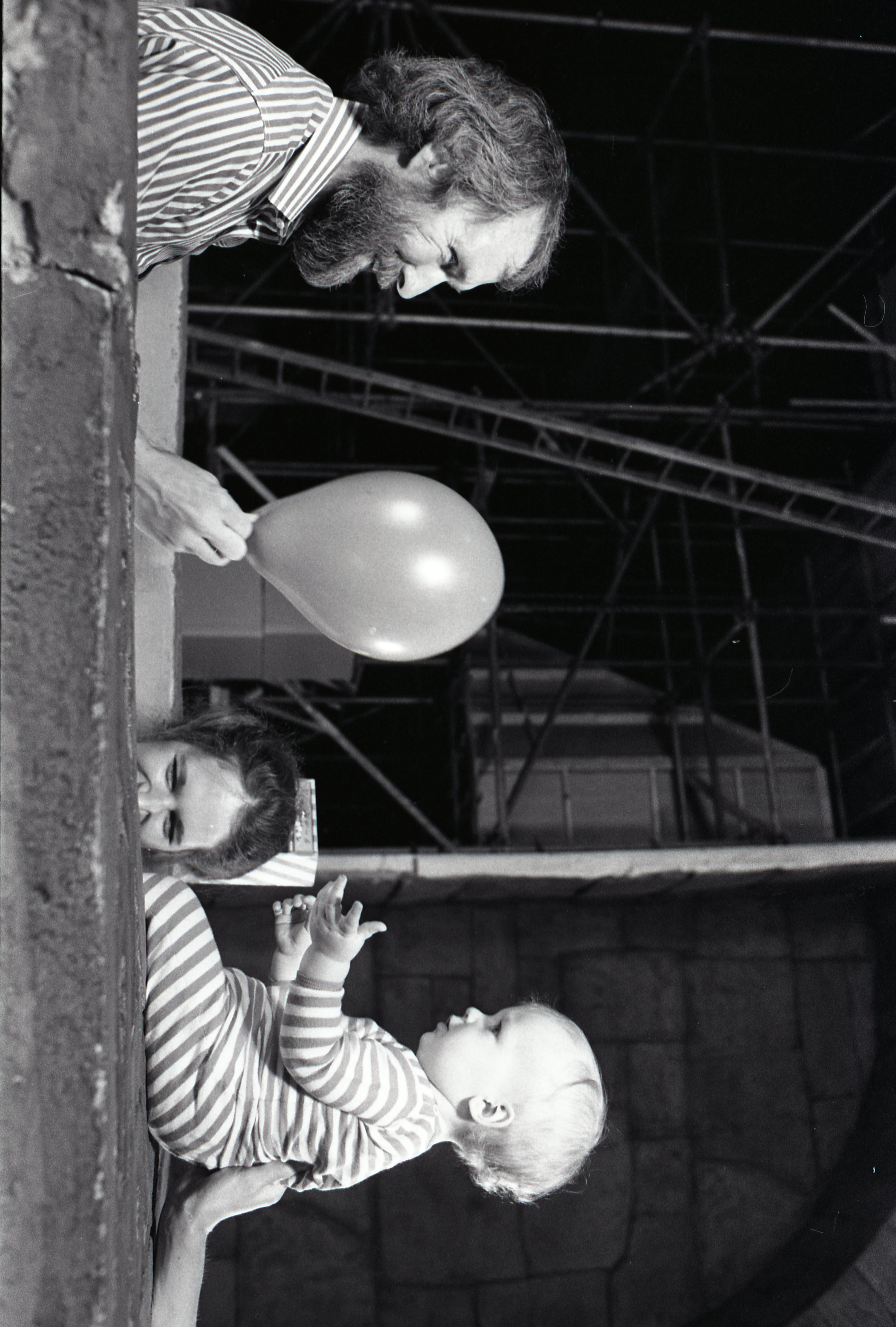

The beginning of Froud’s film career was also the start of a new chapter in her personal life. Cheryl and Jim Henson met British illustrator Brian Froud while filming The Muppet Show in 1977 and eventually recruited him to work on The Dark Crystal. Brian and Wendy met while making the movie, married shortly after, and returned with son Toby in tow for Labyrinth. Toby Froud, who played the striped-pajama-clad baby abducted by David Bowie’s Goblin King, would later work with his parents on Netflix’s Dark Crystal prequel series, Age of Resistance, as Design Supervisor almost four decades later.

Jim Henson seemed to have an instinct for finding artists capable of immersing themselves in his vision. And with the explosion of family-friendly fantasy films in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, famous puppets like E.T., Falkor, and Gizmo came to life through a combination of practical puppetry and new effects. Henson, a pioneer in animatronics, showcased groundbreaking puppets designed by Brian Froud and sculpted by Wendy Froud from a converted London post office.

Jim Henson’s Creature Shop was born to facilitate the production of The Dark Crystal, but without the research, craftsmanship, and inventions that took place there, projects from Dreamchild (1985) to Where the Wild Things Are (2009) wouldn’t exist as we know them.

Cheryl Henson describes an idyllic creative environment.

“What was extraordinary about that period of time was the amount of experimentation,” she says. “Months were spent creating these environmental creatures. The script wasn’t completed, which is something that would never happen now. You can’t start before the script is set, and you won’t build anything that isn’t in the script. It’s not economical.”

Thanks to such experimentation, Jim Henson realized his epic fantasy vision, The Dark Crystal, in 1982 after five years of work. Wendy Froud was instrumental as the lead sculptor of the Gelflings (the film’s elf-like main characters), and Dark Crystal won the Saturn Award for Best Fantasy Film.

The Mother of Yoda

The same year that Froud was hired to sculpt The Dark Crystal’s puppet leads, Kira and Jen, she was loaned out to Frank Oz’s puppeteer team to meld muppet know-how into the fabrication of a two-foot-two-inches tall Jedi Master. British artist Stuart Freeborn had already done a few sculpts at that stage, but they weren’t quite right.

In Laurent Bouzereu’s book Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays, George Lucas says he wanted Yoda to be the traditional kind of character you find in fairy tales and mythology. Froud recalls that Jim Henson said to Frank Oz, “Why don’t you let Wendy come in as she can sculpt and make puppets?”

“We had no idea Yoda would be so iconic,” she adds.

“She single-handedly formed the body out of 1-inch sheet foam.”

Part of Froud’s job was ensuring the final puppet followed principles acceptable to Oz in collaboration with Freeborn and special effects expert Nick Maley.

“What I first did was make a hand puppet out of soft foam, cutting with scissors and razor blades,” she says, “which is how we did Miss Piggy, to begin with.”

Maley, an Emmy-winning VFX artist and the senior tech in the Creature Shop, has written extensively on his blog ThoseYodaGuys about the 10-month process of creating Yoda and Froud’s role in that process:

“She single-handedly formed the body out of 1-inch sheet foam. If I remember correctly, she also modeled Yoda’s hands and feet and single-handedly fabricated the ‘stand-in Yoda,’ made entirely from cut foam, which was used to line up shots during camera setup. I do remember her spending some time working on the clay model of Yoda’s head too.”

It was Wendy who came up with the technique to operate Yoda’s ears, which she fitted using methods Oz was accustomed to. Freeborn spent five months on the modeling stage alone, where Froud could produce up to five heads or faces in a day before a final prototype was approved. Originally, Yoda was young, almost gnome-like.

The Empire Strikes Back premiered in 1980. The following year, Brian and Wendy married in Devon, England. Cheryl recalls the Hensons all attended the wedding.

“It was glorious,” she says, “with medieval influence and music.”

By 1985, the Froud family and Cheryl were filming Labyrinth. Wendy was responsible for the Junk Lady, Goblins, Fairy Lichen, and Birds. Between The Dark Crystal and the Lucas-produced Labyrinth, Froud and her team experimented with new puppetry techniques, like the use of radio-controlled mechanisms to change facial expressions.

But after Labyrinth’s release, Froud didn’t work with a mainstream studio again until 2016, when Four Kids and It (based on a classic British children’s novel) began shooting.

The Frouds created “It,” a puppet voiced by Michael Caine, but what started as a combination of computer animation and puppetry went full CGI in the end.

“People say they want puppets, but they don’t have the faith,” Froud laments. “They don’t fully believe."

Four Kids and It cost an estimated $6.5 million to make and earned just $588,001 at the box office.

Froud’s retreat (and return)

Wendy filled the intervening years creating illustrated books, dolls, and faeries. She also produced meditation apps, workshops, and DVDs on the art of sculpting and dollmaking. During the ‘90s and ‘00s, shifts in technology enabled Froud to expand her art, but technological advancements also played a role in her departure from moviemaking.

“CGI was starting to become more common,” Wendy says. “I think any puppet designer or puppeteer had a hard time during that period. For quite a while, nothing was happening, but now I think audiences are realizing CGI can’t achieve everything. There is a renaissance in the craft and desire for puppetry again.”

While the rise of CGI limited job opportunities, that’s not the only reason for Froud’s retreat from the industry. Wendy says she never had an interest in moving to Los Angeles or London. The Frouds have lived in the small English town of Chagford in Devon since the early 1980s, traveling to bigger cities to work on films.

“There is a renaissance in the craft and desire for puppetry again.”

Terri Windling, who collaborated with Froud on the 1999 book Midsummer Night’s Faery Tale, calls the Froud house “enchanted.” On her website, Winding writes:

“The Froud family’s thatch-roof farmhouse sits buried in ivy down a quiet country lane in England’s West Country. Its old front door, with a goblin door-knocker, is a doorway into Faerieland. Inside is the kind of enchanted house one usually finds only in fantasy books: full of carved medieval furniture and tapestries, costumes, masks, old books, puppets, and magical props from films. Faeries, goblins, trolls, and sprites stare down from Brian’s paintings on the walls, and cavort in the shape of magical dolls and sculptures created by Wendy.”

In 2019, Wendy returned to big-budget work for Netflix’s The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance. Director Louis Leterrier insisted that his reimagined prequel “would depend on puppetry," only sparingly incorporating CGI. And so, 37 years after the original Dark Crystal, Froud was sought out once more.

To writing partners Jeffrey Addiss and William Matthews, the co-creators of Age of Resistance, Froud became an on-set anomaly who transcended title and “just is.”

“How do you put a title on someone who has the technical skill to look at what everyone is doing and very quietly point out, ‘But the Gelflings have wings, so we need to change the back of the costume to accommodate for the fact that they have wings’? Wendy took pieces of other creatures and changed them in ways you don’t recognize,” Matthews says. “And they feel complete. As characters, as creatures, they felt utterly convincing and part of the world.”

“People spend months developing creatures,” Addiss says. “She can walk through a room, gathering bits, and by the end have the perfect little thing. Then put it in frame, and everyone is like, ‘Yep 100 percent.’”

Before signing off, Addiss adds, “We are usually too busy, but for a piece about Wendy, you make time. She is so talented, and we were so lucky to have her.”

Froud didn’t mind “helping things along.” If her creatures were used, great. If not, that’s fine too. Returning to the world of The Dark Crystal felt like returning home and sparked something she hadn’t felt in years.

“Hopefully, we aren’t completely done in this world,” she says.

Froud on Grogu

The same nature that makes industry insiders adore Wendy also makes her too unconventional to fit the Hollywood mold.

“She’s an artist, a creator, and a dollmaker, and that is who she is,” Cheryl Henson explains. “Loves working on films, but she doesn’t change who she is to work on a film.”

Froud never attempted to climb the Hollywood hierarchy.

“It really didn’t appeal to me, to be honest,” she says. “I didn’t want to. I never belonged in Hollywood. It’s a nice place to visit. But I belong here, so far removed from Hollywood and the industry.”

That doesn’t change the pride she takes in her work and the timeless connections her puppets have made with people. “My name at the end of the movie doesn’t do it for me at all. But the effect of the creatures, we’ve had people say to us, ‘You changed our lives for the better.’”

“I love Baby Yoda.”

Lack of public recognition, as Cheryl explains, is part of the territory for puppeteers. “The industry tends to look at the puppet as a costume the actor is wearing.” But demand for puppetry is on the rise again. Guillermo del Toro insisted that his latest project, an adaptation of Pinocchio, use stop-motion even if that leads to a higher budget. Toby Froud, now a puppet sculptor with Jim Henson’s Creature Shop, will be helping provide practical effects.

And then, of course, there’s Grogu. Over 100 artists from Legacy Effects had a hand in creating the phenomenon that is Baby Yoda, including five puppeteers.

“I love Baby Yoda,” Froud says. “How could you not? I know one of the women on that team. She’s a friend, it all feels so connected. The Force has been with me. The Force is strong.”

Ultimately, the same art form that pushed Wendy Froud’s willingness to believe is what made her realize that she could bring creations to life. Her goal has always been to bring magical creatures into the lives of everyday people, and film was just one of many mediums for her life’s work.

“One of the most tragic moments in my life, in my early teens, was the realization that I was too old for Peter Pan to return for me,” Wendy says. “But now, I create the magic. I am Peter Pan, I’m Tinkerbell, I’m Wendy, and I love that idea.”