In September 2023, the UK prime minister, Rishi Sunak, announced that landlords will no longer be required to improve the energy efficiency of their rental properties. The announcement marked a departure from decades of commitment to the government’s sustainability objectives, including efforts to reduce the UK’s dependence on imported energy.

This dependence remains a threat both to the UK’s energy security and to addressing the growing number of people that are trapped in fuel poverty throughout the country.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, energy prices have soared. Under the UK’s current energy price cap, which is set every three months by government energy market regulator Ofgem, the average annual gas and electricity bill for a “typical” household is £2,500. This represents a 27% increase compared to the price cap in the summer of 2022 and a 96% increase compared to the price cap from the winter before.

My research, published in November 2023, suggests that rising energy prices could have a disproportionate effect on people living in deprived areas. This is because their homes tend to use much more energy than they should need to due to things like a lack of insulation.

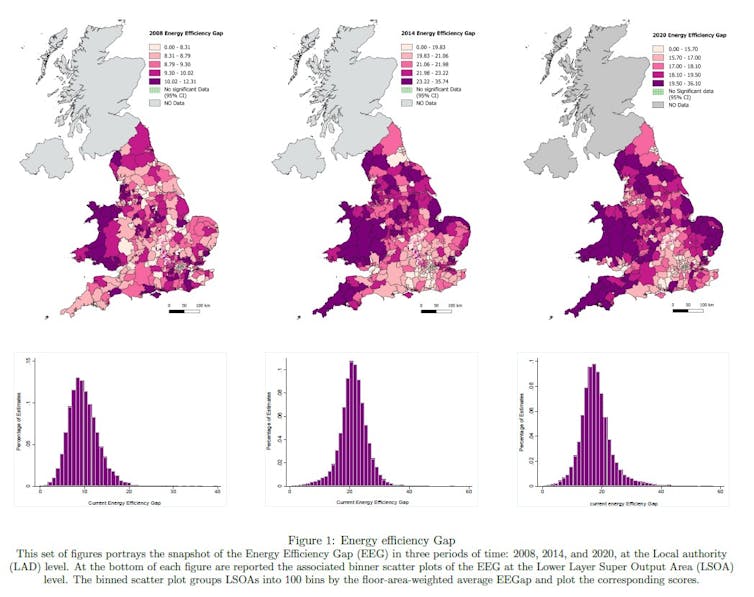

The difference between the amount of energy that could be consumed if a house was perfectly energy efficient compared to how much energy is actually consumed is known as the “energy efficiency gap”. This gap is greater for households living in deprived areas, meaning a higher proportion of their already limited incomes has to be spent on energy.

Over the past decade, several attempts have been made to improve the energy efficiency of UK households. The UK government’s Great British Insulation Scheme, for example, offers financial support for installing home insulation. However, despite such efforts, the size of the energy efficiency gap has remained persistent with substantial regional variation across England and Wales.

Closing the energy efficiency gap is a complex endeavour. My current research shows that the energy efficiency gap is the result of the intertwined relationships between several different factors. Three of those factors are discussed below.

The energy efficiency gap in England and Wales (2008–2020):

Understanding of energy efficiency

People’s perception of the benefits that stem from energy-efficient behaviours has a significant impact on their choices. If people are unaware of the importance or do not deem it necessary to enhance the energy efficiency of their homes, they may not be willing to adopt energy-saving practices.

In my latest research, also from November 2023, I used education level as a proxy for people’s willingness to engage in energy-efficient behaviour.

My analysis, which was conducted over a sample of around 18 million households in England and Wales, suggests that people adjust their energy-efficient behaviours faster in areas where the average resident possesses higher levels of education. A person was deemed to have a high level of education if they held a post-secondary diploma or higher degree.

These findings are in line with the Opinions and Lifestyle Survey conducted by the Office for National Statistics in 2021. This showed a positive relationship between households’ understanding of the benefits of adopting energy-saving measures and their decision to use energy more efficiently.

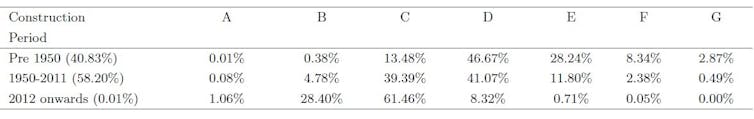

Construction period of a home

Energy efficiency gaps are also influenced by the age of the property. The UK’s housing stock is among the oldest and least insulated in Europe. This means that a lot of heat can quickly be lost through walls, windows and doors.

Older homes that were constructed in an era before energy efficiency became a central concern (before 2012), are generally less energy efficient. This translates to larger energy efficiency gaps, higher energy consumption and, as a consequence, higher utility bills.

By contrast, modern homes are often constructed using more energy-efficient building materials and features that are designed to retain heat effectively. These include double or triple glazing, energy-efficient boilers and cavity wall insulation.

The link between energy efficiency and age of homes:

The existence of larger and persistent energy efficiency gaps is a phenomenon that affects anyone living in an energy-inefficient home. However, my research shows that it has the potential to affect society’s most vulnerable disproportionally.

Homes in economically deprived areas tend to be less energy efficient. As a result, households living in these homes are forced into spending a higher proportion of their disposable income on the cost of basic needs such cooking and heating.

In previous research, which was published in August 2023, I found that energy bills amounted to 47% of the disposable income for poorest tenth of families in Britain over 2022, up from 23% in 2020.

Financial status

Differences in household incomes play a significant role in determining the ability of people to implement energy-efficient improvements in their homes. Wealthier households can quickly incorporate these upgrades.

On the flip side, economically disadvantaged households struggle to even make ends meet, which means investing in energy improvements is more difficult. As a result, they find themselves restricted to the use of outdated and inefficient equipment, ultimately leading to higher energy efficiency gaps, higher energy consumption and increased costs. This situation is applicable to both homeowners and renters alike.

The government can do more to improve the energy efficiency of all UK homes. It could, for example, retrofit older buildings and create campaigns to improve energy literacy.

However, a better understanding of the relationship between local deprivation and households’ energy efficiency gaps is needed to guide economists and policymakers towards identifying the challenges that vulnerable people face in adopting new energy-saving technologies.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 20,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Gissell Huaccha does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.