Ami Vitale is an award-winning nature and humanity photographer and a Nikon, Canson Inifinity and Luminar Neo Ambassador. She has travelled to more than 100 countries to document war zones and the individuals dedicating their lives to preserving endangered animals and she believes in the power of staying longer, to get fuller, more insightful stories.

Her stories are as intricate as they are fascinating, and she is also a filmmaker, a speaker (you can watch her TED talk) and an activist, having started her own not-for-profit, Vital Impacts, to empower the youth through arts. She is also

As part of our Day in the Life series, I spoke to her about the time she dressed up as a panda (it was smellier than you'd imagine), her work in war zones and why she believes people and wildlife are inextricably intertwined.

Tell me about a typical day in your role

It sounds romantic to travel the world but the reality is often much different. I look back on experiences I had and wonder how I got through some of them. They were sometimes unimaginable, often lonely, and occasionally utterly terrifying. There is also the occasional monotony and the unavoidable encounters with rejection. I have learned to be thoughtful about how and where I work. This involves a considerable amount of time intensively planning, researching and meticulously thinking through how to craft each story. And within these challenging moments, lies a profound truth: the most gratifying journeys demand persistence, the ability to shake off rejection, and finding joy in the little details.

How did you get into photography?

As a young woman, I was painfully shy, gawky and introverted. I did not have a clear direction or know what I wanted to be when I grew up. Something incredible happened when I picked up a camera. It gave me a reason to interact with people and took the attention away from myself. I got my courage from being behind the camera. The second I had it in my hands, I felt like a superwoman. By putting attention on others, it empowered me.

Photography gave me courage and helped me realise that being an introvert was not a weakness – it actually gave me the ability to listen, to truly hear others' stories. It became my passport to engage with the world around me. Today, photography and storytelling are much more than a tool for my own self-empowerment. They are a tool for creating awareness and understanding across cultures, communities, and countries; a tool to make sense of the commonalities in the world we share.

Tell me about a work-related challenge and how you approached it

Surprisingly, the giant panda story was one of the most challenging stories I've worked on. Getting access to a very rare, finicky endangered animal was not easy. There are only a few thousand animals worldwide and the Chinese treat them as a national symbol – each panda is closely guarded and watched. They are multi–million dollar bears that everyone treats with kid gloves, and they are highly vulnerable. Getting access to this story took a lot of time, patience, trust, and the right connections.

Once I did have access, there were other challenges. Being close to pandas, without interfering with their biology and conservation, and in a way that is acceptable to its very protective minders, was not simple. In order to do this, I had to dress up as a panda. It's harder to rock a panda suit than you may imagine, particularly when it’s scented with panda urine and sometimes panda faeces. Pandas go by smell, not sight, so it was a stinky endeavour but one I’d happily do again if asked.

Today, there are fewer than 2,000 giant pandas in the wild. Their breeding secrets have long resisted the prying efforts of zoos, and the mountainous bamboo forests they call home have been decimated by development and agriculture. For over thirty years, researchers from the reserve have been working on breeding and releasing pandas, augmenting existing populations, and protecting their habitat. And they’re finally having success. The slow and steady incline in the population of giant pandas is a testament to the perseverance and efforts of Chinese scientists and conservationists. By breeding and releasing pandas and protecting their habitat, China may be on its way to successfully save its most famous ambassador and, in the process, putting the wild back into an icon.

Which project are you most proud of?

I don’t have a strong sense of 'pride' regarding my work; I see myself merely as a messenger for the extraordinary efforts of other exceptional individuals. Impactful narratives require time to unfold, and the most profound stories are those that have taken years to tell.

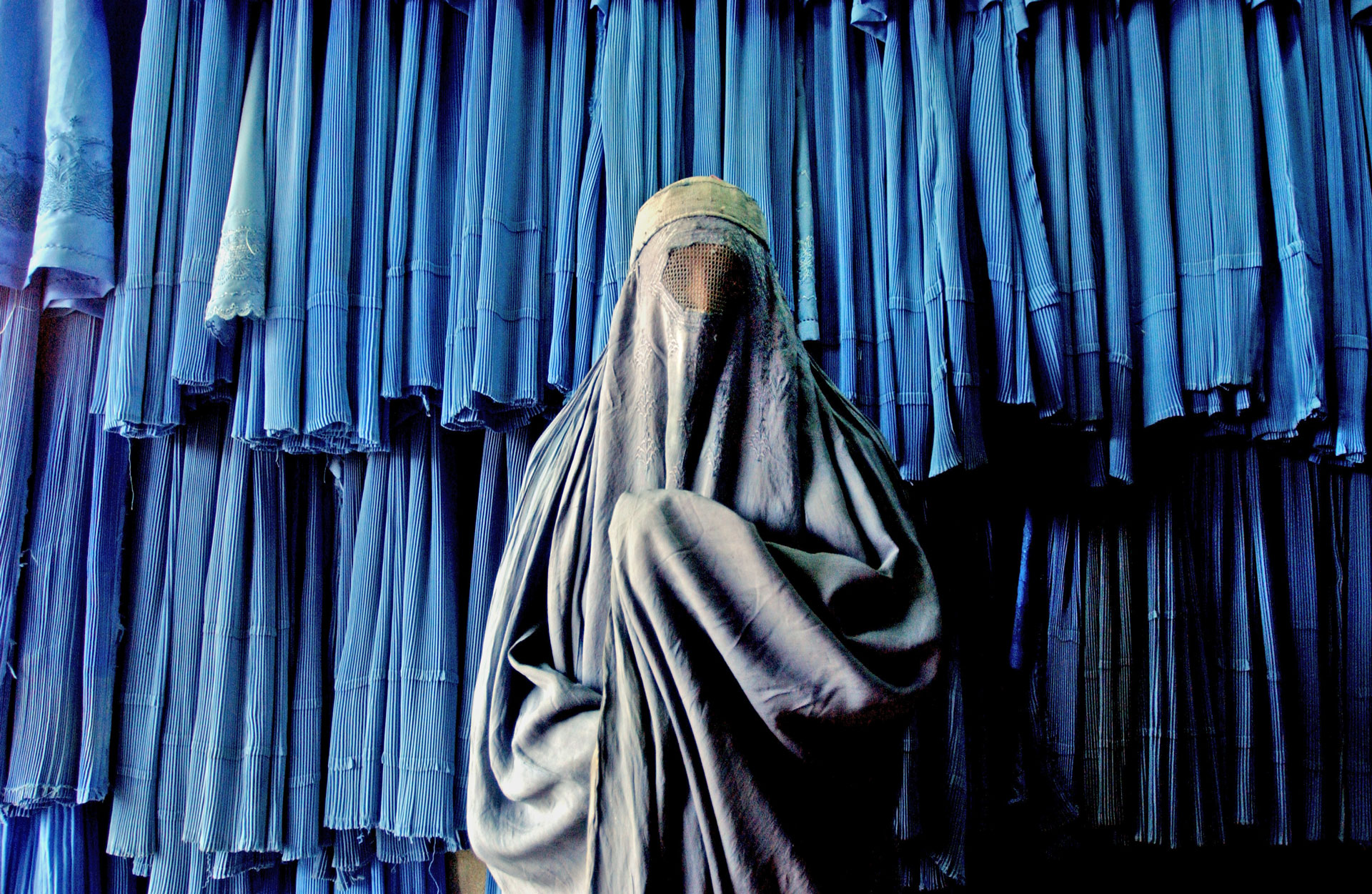

I spent four years in Kashmir documenting the conflict between India and Pakistan and its toll on the people caught in the geopolitical crossfire. In northern Kenya, I dedicated over ten years to collaborating with a Samburu community, actively engaged in the rescue and rehabilitation of orphaned elephants. Another ongoing narrative I work closely on spans 15 years, involving a group of scientists racing against time to save the northern white rhinos from extinction. Lastly, I collaborated for three years with conservationists and scientists documenting their extraordinary efforts to safeguard Giant Pandas.

I get immense joy from spending time on stories and revealing details that surprise people. I also have discovered that taking time to let these stories unfold and earning trust from the communities I work with, leads to meaningful positive impacts. Ultimately, I want these stories to be a catalyst for change and to inspire people to become changemakers.

How has your work in war zones affected your outlook?

I was 26 when I began working in the Balkans, then Gaza, Sierra Leone, Angola, Kashmir, and places you may never have heard of, like Casamance in West Africa or the Maoist rebellion in Nepal. I set down this path and became a war photographer primarily focused on only the horrors of the world. The devastation, the stories of resilience, and the palpable consequences of political decisions challenged my preconceived notions. This journey forced me to confront the harsh realities of human suffering and the profound consequences of global dynamics, deepening my understanding of the intricate web connecting nations and people. It was a powerful lesson in the interconnectedness of our world and the ripple effects of geopolitical decisions on communities far removed from the centres of power.

After a decade, I realised another profound truth; I had been telling stories about people and the human condition, but the backdrop of each and every one of these stories was the natural world. In some cases, it was the scarcity of basic resources like water. In others, it was the changing climate and loss of fertile lands, but always it was the demands placed on our ecosystem that drove conflict and human suffering. Today, my work is not just about people. It's not just about wildlife either. It's about how the destinies of both people and wildlife are intertwined and how small and deeply interconnected our world is.

How did you get into filmmaking?

Photography led me to become a filmmaker. I fell in love with the way one single photograph can instantly connect people with its universal language. Later, with the advent of DSLR technology and its ability to seamlessly switch between stills and moving images, I discovered the power of filmmaking.

How do you decide when to use film vs photography?

Crafting films is a nuanced and resource-intensive process. It requires a considerable investment of time, collaborative effort, and financial resources. Unlike the spontaneous capture of a photograph, filmmaking demands meticulous planning, coordination with the right team, and a budget substantial enough to bring the envisioned narrative to life. Some stories are better suited for filming vs photography but I will often try to use both mediums if it will help to inform and influence change.

How do you research a subject you want to capture?

As journalists and storytellers, we often research and try to learn everything we can before we begin working on a story. While research is important, there is danger in going with the narrative already written before we even set foot in a new place. I learned that it takes time to truly listen to and understand one another's stories. Stories are often messy and complex. I've learned to embrace that complexity, and when we take the time to listen, the stories emerge without preconceived notions.

When I started my work as a journalist, I was encouraged to 'parachute in' and bring back 'the story' and then leave. We often work with the narrative already prewritten in our heads before we even begin. It takes years to even begin to understand the subtleties, context, and deeper truths that exist. I have chosen to work in the same communities, on the same stories, sometimes for more than a decade. By taking time, I am able to hear and share a multitude of narratives. And in this way, through a multitude of stories, I hope that a balance is maintained. If you get beyond the headlines, if you peek under the veil and truly take time to understand each other's stories, only then do you understand that the 'sensational' we are asked to share, transforms into a different story, one of sensitivity and interconnectedness.

Tell me about your not-for-profit, Vital Impacts

Never before has it been so clear that our fates are inextricably linked to the life around us, whether we see it or not. This is a moment to reimagine our relationship with nature and with each other. We all need to do all we can to care for the plants and critters that inhabit the earth. Our future happiness depends on them.

My mission as founder and Executive Director of Vital Impacts is to use photography to create empathy, awareness, and understanding. The survival of the planet is intertwined with our own survival. Our organisation brings together today's most compelling environmental artists who have come together to rally around a cause – inspiring the next generation of environmental stewardship.

Their award-winning imagery brings to life the biodiversity crisis and the people and programs working toward a sustainable future. Fine art print sales and donations are supporting grassroots conservation organisations, and our educational speaker series, mentoring, and grant programs are fostering the next generation of conservationists.

We work with both the most established artists in the world but are also particularly committed to amplifying emerging talent to foster and support the next generation of environmental photographers and storytellers. Within its first year, Vital Impacts parlayed a generous startup grant of $25,000 into more than $2,000,000 in the sale of fine art prints and fundraising. We passed these profits onto unique conservation and humanitarian efforts around the globe.

We have just launched a second round of $20,000 grants and a mentorship program.

You have recently become a Luminar Neo’s Global Ambassador. Can you tell more about that?

I am honoured to announce that I am a Luminar Neo’s Global Ambassador. Skylum, the company behind Luminar Neo, is an extraordinary team, and they have created a tool that helps me streamline my workflow when I am on a deadline. As a documentary photographer, I believe the power of a photograph lies in its authenticity and the genuine reflection of reality. I have very strict parameters in post-processing to only do the bare minimal adjustments that do not alter what I saw while creating images. For all of us who work in this genre, we do not enhance or alter our images for the sake of aesthetics. To me, the power of photography is in the meaning of each image. It's not only about making beautiful photos but rather telling a powerful story.

What's your dream project?

All the projects I'm currently working on are my dream projects!

What career advice would you give your younger self?

To slow down, spend time with people, go deeper into each story, and reveal more than a series of 'exotic' images. Sticking with a story for years helps us understand the complexities, characters, and issues that are not always immediately obvious. Empathy and earning trust is the most important tool one can have.

Find out more about Ami Vitale via her website.