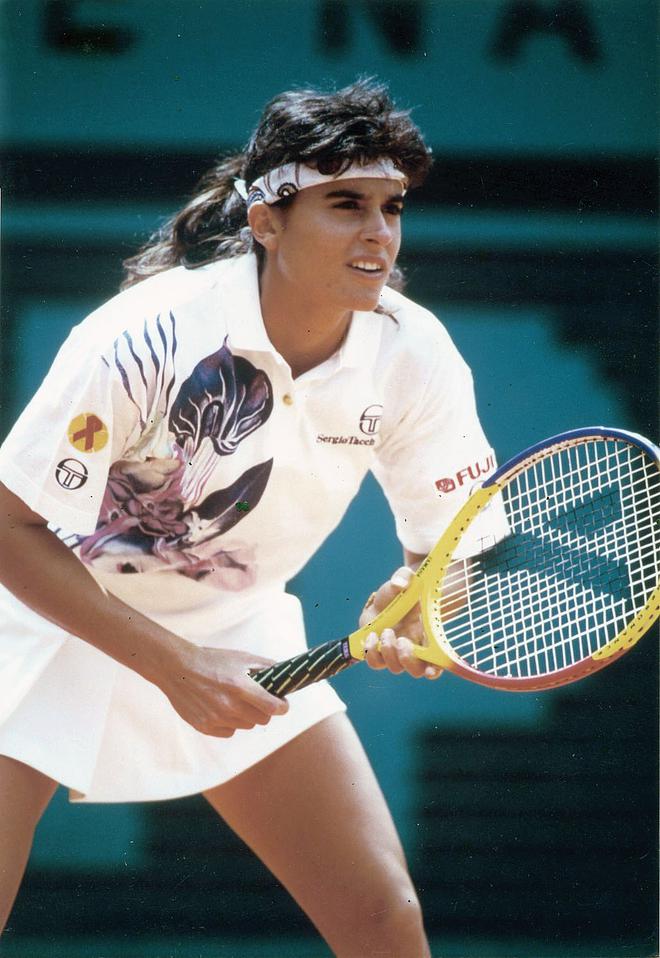

Bring me the sweat of Gabriela Sabatini, wrote the poet Clive James, going on to add, In a green Lycergus cup with a sprig of mint,/ But add no sugar –/ The bitterness is what I want./ If I craved sweetness I would be asking you to bring me/ The tears of Annabel Croft.

It was the time of Martina and Steffi and Francois and Tracy and Hana — we were on first-name terms with them all. Sabatini won the U.S. Open in 1990, Croft was Britain’s top-ranked player who retired at 26. It was the time of ball boys selling off Sabatini’s sweat-stained towels for ten pounds each.

Sport is not necessarily about talent attracting the fans and the money. As more than one writer has pointed out, it is a soap opera. Fans and advertisers, television and media come for the people, their stories, their love life, their weaknesses, their looks, their idiosyncrasies.

Where are today’s Sabatinis and Crofts? Or Clive Jameses, for that matter? The best we can do is put together Iga Świątek, Aryna Sabalenka and Elena Rybakina as the female counterparts of the Federer-Djokovic-Nadal trio at the top of the game. Does that reflect failure of imagination in writing or is something lacking in the women’s game itself?

More appeal for men’s tennis

In an essay in the 1980s, novelist Martin Amis said, “The women’s game is now more interestingly poised than the men’s — as well as being better fun to watch.” Last year, former Wimbledon champion Amelie Mauresmo said, “Right now you have more attraction, appeal in general, for the men’s matches.”

At this year’s French Open, former player and commentator Sue Barker said women’s tennis needs more big rivalries. “What we need is a few really good players to be in the Slam finals for a few years and build up that rivalry.”

Between 2016 and 2022, the No. 1 and No. 2 women players faced each other in a tournament final only on two occasions. The game needs rivalries — or dominance — to attract fans. It needs money too, something the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) has been made conscious of. In March, WTA sold off 20% stake in its Tour to a private equity firm, CVC Capital Partners.

More tellingly, it decided after a 16-month suspension that women’s tennis would return to China.

In November 2021, Chinese player and world doubles No.1 Peng Shuai had made allegations of sexual harassment against a high-ranking Chinese Communist Party official on social media. Her account was abruptly taken down and she wasn’t heard from. WTA banned China as a result, saying the boycott would be lifted only after Peng was seen to be safe. At the time, China hosted more women’s events than any other country.

This year, WTA decided to return to China, arguing that “by returning, more progress can be made”. A WTA statement said, “We received much praise for our principled stand and believe we sent a powerful message to the world. But praise alone is insufficient to bring about change.”

The season-ending WTA finals to be held in Shenzhen in China for 10 years from 2019 is part of China’s $500 million investment in women’s tennis for the period. The finals itself is a $14 million tournament. Last year, it was held in Texas during the ban, but will now continue in Shenzhen till 2028 as originally agreed.

Billie Jean King and the fight for equal pay

This year, Wimbledon celebrates the 16th anniversary of equal prize money for men and women. It was 50 years ago that, thanks mostly to former World No.1 Billie Jean King, the US Open first had equal pay, but the other three majors took their time, with Wimbledon finally catching up only in 2007.

Other tournaments — tennis is more than the sum of its Grand Slams — haven’t all got there yet. Last year, it was calculated that combining all tournaments except the Slams, the total prize money awarded on the men’s tour was 75% higher than on the women’s. King’s revolution, carried forward by Venus Williams, has some way to run yet.

But it isn’t just the money, although there is a paradox here. Too much of it and players tend to retire early, too little and there’s no motivation.

Earlier this year, Wimbledon champion Garbiñe Muguruza, 29, took a break saying she was “spending time with family and friends”. Her ranking dropped from No.1 to No.132. In May, she was engaged to a fan who recognised her on the streets of New York and asked for a selfie with her.

More dramatically, Ashleigh Barty, also Wimbledon champion, retired a year ago following diminishing interest in the sport. Barty, 25, and ranked No.1, quit “to chase other dreams”. Another Wimbledon champion, Simona Halep, 31, is suspended after testing positive at the U.S. Open last year. Naomi Osaka, 25, has taken a break to have a baby. These four players won 11 Slams in the last seven years.

Tennis, like all individual sports, relies on big names and big rivalries for its sustenance. Chris Evert vs. Martina Navratilova was one such, as was Steffi Graf vs. Monica Seles, and more recently, Venus Williams vs. Serena Williams.

Champion’s dilemma

How do today’s stars — Poland’s Świątek, Belarus’ Sabalenka and Kazakhstan’s Rybakina — measure up? Can they extricate women’s tennis from the ordinariness it seems to have slipped into?

Świątek is best equipped to do so. Already a four-time Slam winner at only 22, she can win 10 or 15 Slams, says German star Boris Becker. Her hero Rafael Nadal has won 22, but more significantly, worked at becoming nearly as comfortable on grass and hardcourts as he was on clay. When Świątek wins her first Wimbledon title — and this could be the year — she would have taken another step towards becoming an all-time great.

She will also come up against the champion’s dilemma, having to choose between repeating and reinventing herself. From all accounts, she displays a balance, an awareness of the world outside the tennis bubble so evocatively described by Amis in the essay quoted earlier: “The system prescribes a life of unique enclosure, in which every contact is featherbedded, insulated, mediated. Fixers, helpers, PR people, guys with guns everywhere: these extras are just part of the scenery for the gazelles and snow leopards of modern tennis, a protected species in their bijou theme park.”

Świątek’s support for Ukraine in the war against Russia, her highlighting the mental issues in the game (and contributions to mental health charities), her decision to travel with a sports psychologist, Daria Abramowicz, already sets her apart from the monomaniacal introverts who populate the tennis world.

She does crosswords and Sudoku on tour, travels with Lego blocks and books and looks forward to reading George Orwell to understand the world better and improve her English. “It is impossible to become a champion when you don’t have a fundamental joy and your needs fulfilled and satisfied as a human being,” says Abramowicz.

Świątek, who won 37 matches in a row in 135 days last year, is best summed up by Evert, possibly the finest clay court player before her. “She’s a leader that doesn’t yell at the top of a mountain,” said the 18-time Grand Slam champion. “She’s more soft-spoken. Yet when Iga speaks, people will listen.”

Forget Sabatini. Bring me the sweat of Iga Świątek.

The writer’s latest book is ‘Why Don’t You Write Something I Might Read?’.