Beyond questions of athletic performance, the Milano Cortina Winter Olympics raise questions about climate urgency and growing expectations for environmental responsibility at mega sporting events. Aware of the carbon footprint associated with spectator attendance, the organizing committee has implemented measures to encourage spectators to adopt more eco-responsible behaviours during these Olympic Games, which end on February 22, before resuming in March for the Paralympic Games.

What are these measures, and what is their real impact?

As a doctoral student in political science at the Université de Montréal, my work focuses on both climate communication and environmental policy development, including in the sports sector.

After attending the 2024 Paris Olympics, often touted as greener, I had the opportunity to attend the Milano Cortina Olympics during the opening weekend at Bormio and Livigno.

À lire aussi : À la veille de l'ouverture des JO d’hiver, quelles attentes environnementales ?

Spectators: the champions of emissions

The Winter Olympics, although smaller than the Summer Olympics, attract large crowds to the mountains. In Italy, organizers expect to welcome some 2.5 million spectators across all venues. These will be the most dispersed Games in history, with four venues spanning an area of more than 22,000 km².

Spectator travel to the Games is generally the main source of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the event. For example, during the Paris 2024 Games, this alone accounted for nearly half of the total carbon footprint, or 49 per cent.

The crowds also bring other challenges, particularly in terms of waste management. The catering services offered to spectators at the Milano Cortina venues, as well as waste treatment, are expected to account for more than 15,000 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent.

As a result, several initiatives are being implemented to limit the impact of spectators.

Better transportation for less pollution

Organizers have little leverage to influence the air travel of spectators travelling to northern Italy, but they can influence the modes of transportation visitors use after they arrive.

In particular, planners have restricted road traffic near Olympic facilities to address both safety and environmental concerns. Residents and spectators who wish to travel there by car must obtain a pass, which must be requested several weeks in advance and displayed on the windshield, where it is checked at the main access points. While this measure does not explicitly ban cars, it greatly reduces their appeal.

To encourage alternatives, free park-and-ride facilities have been set up on the outskirts of sites, with paid shuttles available to transport spectators to venues. Outside Milan, most venues are not directly accessible by metro or train, so free shuttles have been put in place at certain stations.

Finally, for spectators who are lodging higher up in the valleys, as was the case for me, local public transportation is an option. Although they require paying a fare and mean longer travel times, public buses allow spectators to reach venues without using a private vehicle.

Gold, silver… and plastic

Do you remember the Phryges, the 2024 Paris Olympic mascots that went viral on social media? In Milano-Cortina, you’ve probably heard of their heirs, Tina and Milo, whose names echo the city names CorTINA and MILanO.

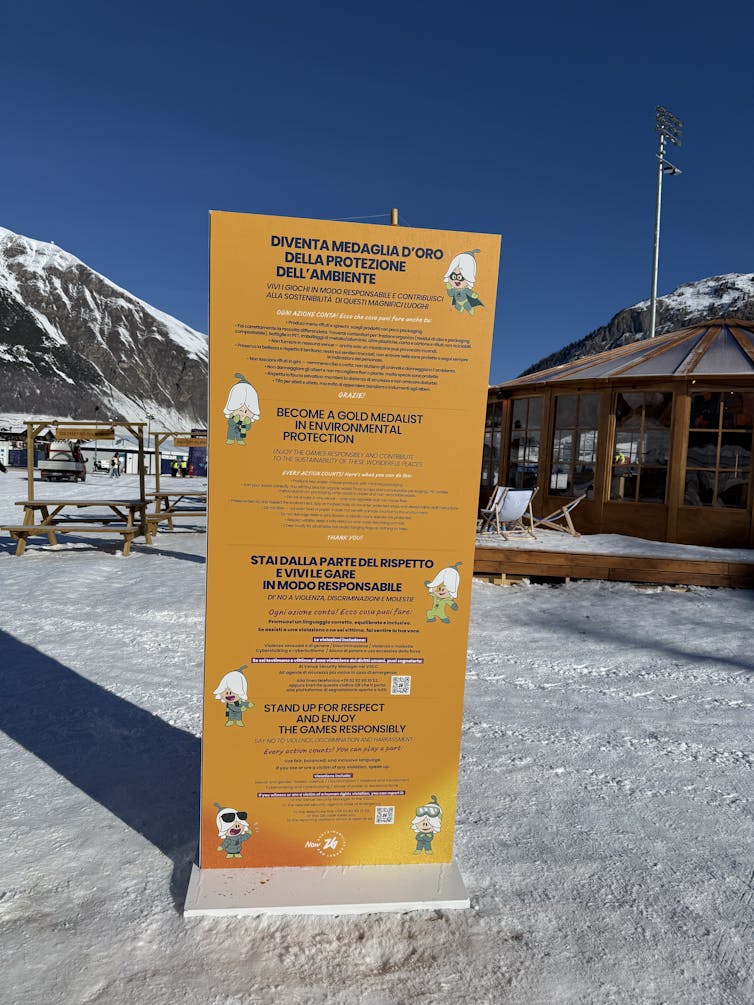

However, you might not have heard of the Flo. Unlike the official mascots tasked with entertaining the crowds, these six little snowdrop flowers have a very specific mission: to promote recycling on site.

Their name — a play on the English expression “go with the flow” — echoes the anti-waste campaign, “Follow the Flo.”

The mascots appear on signs that explain waste sorting stations installed near collection points at Olympic venues, thereby helping to raise spectators’ awareness of their actions in a fun way. In addition, soft toys bearing their likeness are available for purchase, extending this initiative beyond the recycling areas themselves.

A mixed performance

No definitive data is yet available on recycling or shuttle and public transport usage at the Games, but it is already possible to share a few observations.

Firstly, the modes of transport provided appear to be victims of their own success. In terms of local bus service, organizers actually underestimated spectators’ enthusiasm for this service.

In Livigno, a high-altitude Olympic venue, there is only one bus per hour. At the end of the competitions, the inevitable happened: endless lineups, spectators forced to wait in the cold, and a general feeling of improvisation.

However, to be fair, access to the site is, in itself, a logistical challenge. Once in Bormio, another high-altitude Olympic site, getting to Livigno means travelling along a winding road for nearly an hour and crossing a pass at an altitude of over 2,000 m. This, itself, limits the flow of vehicles and the frequency of shuttles.

Nor have the other venues avoided these logistical headaches. Here, geography brings constraints and patience is required to enjoy the Olympics.

The park-and-ride strategy also has drawbacks. Their number is limited, and some are themselves located at high altitudes, including the one at Aquilone. This choice raises the question: by placing these parking lots lower down in the valley, could the organizers have further discouraged car use and encouraged public transportation?

Risk of greenwashing

Furthermore, while the Flo initiative encourages selective sorting, this cannot be the only solution for reducing the amount of waste the Games generate.

It is surprising that no reusable tableware is offered to spectators and that catering services use recycled cardboard or plastic packaging for the sale of their products. The absence of water fountains for refilling bottles has also led to the widespread use of plastic water bottles.

Although the Flo initiative has good intentions, selling soft toys contributes to mass consumption, which runs counter to the principles of a sustainable economy.

Thousands of subscribers already receive The Conversation’s Canada Daily newsletter. And you? Subscribe today to our newsletter for a better understanding of today’s major issues.

The money raised from the sale of these plush toys does not appear to be reinvested in green initiatives. This is a missed opportunity to boost the impact of individual actions, and exposes the initiative to accusations of greenwashing.

This risk is all the more real given that the initiative is partly sponsored by Coca-Cola, one of the world’s most polluting plastic companies. Coca-Cola was already the subject of a complaint during the Paris Games in 2024.

Efforts to be improved

While environmental initiatives for the 2026 Olympics represent an encouraging first step compared to those of previous Winter Games, they are still insufficient in number and ambition.

It must be said that the benchmark was not high. The 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, like several recent Games, were criticized for their ecological impact.

Ultimately, this also invites us to reflect on the size of these mega sporting events, which have grown considerably over time. Ultimately, unless the number of spectators is limited, the carbon footprint of the Games will necessarily remain high.

Alizée Pillod is affiliated with the Centre for International Studies and Research at the University of Montreal (CERIUM), the Centre de recherche sur les Politiques et le Développement Social (CPDS), and the Center for the Study of Democratic Citizenship (CECD). Her research is funded by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (FRQ). Alizée has also been awarded the Departmental Recruitment Scholarship in Public Policy (2021), the Rosdev Scholarship of Excellence in Environmental Studies (2023), and the Scholarship of Excellence in Public Policy from the Maison des Affaires Publiques et Internationales (2025). She has previously collaborated with the Ouranos consortium, the Quebec Ministry of the Environment, and the INSPQ. She is currently a visiting researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Sport at the University of Lausanne.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.