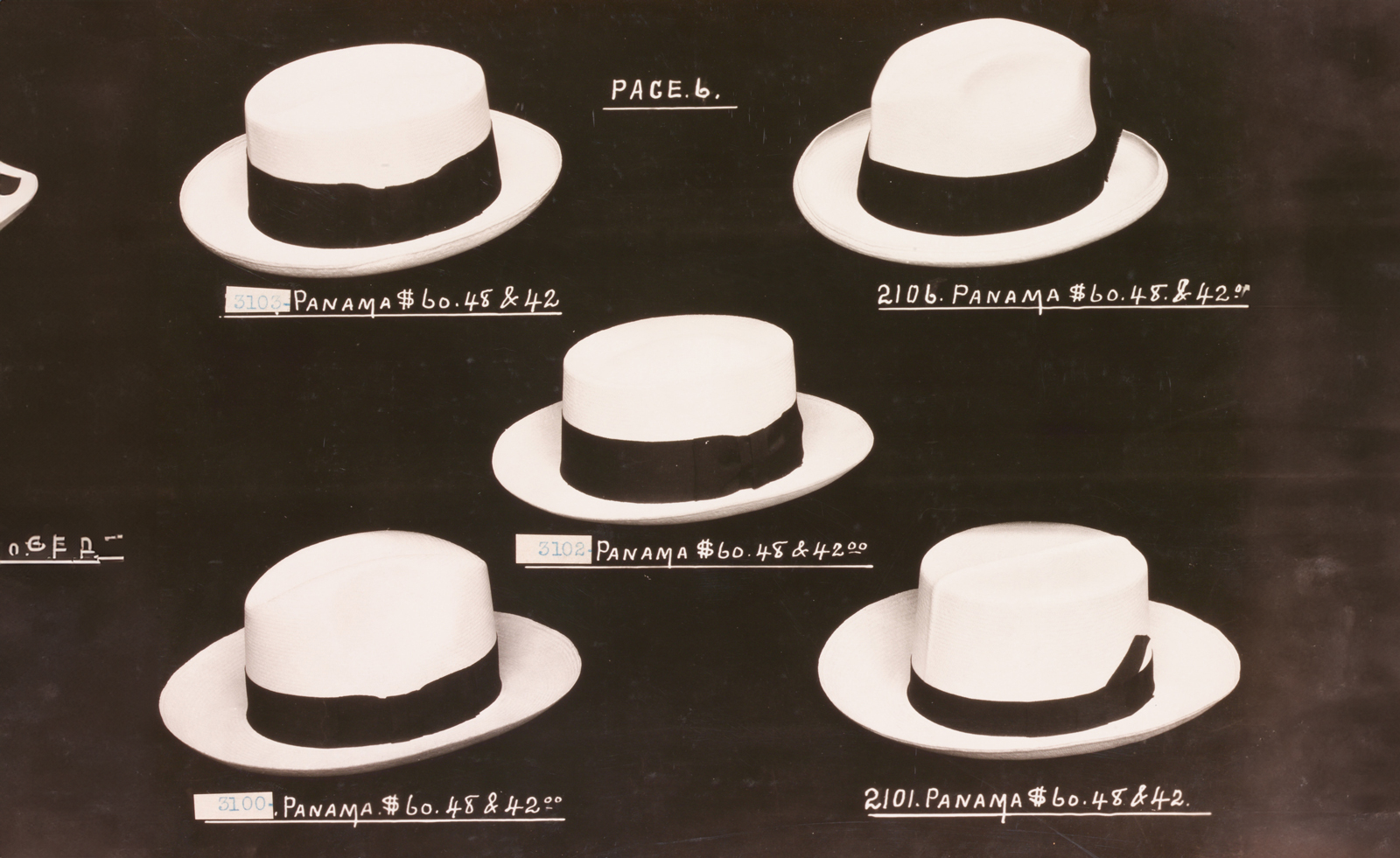

In an advert dated 1916, studio photographer FD Hampson arranges five Panama hats in a 2-1-2 formation. A small shower of white objects against a black background, the hats appear like flying saucers hovering in a blank void. ‘It’s a total transformation that makes the hats sing,’ suggests Virginia McBride, a research associate at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and curator of the recently opened exhibition, ‘The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography’, in which Hampson’s photograph features. ‘Immediately, it summoned for me the work of people like Max Ernst,’ she continues, alluding to the Dada pioneer’s The Hat Makes the Man collage from 1920.

Comprised of more than 60 works from the first century of photo advertising (beginning in the 1850s), the images in the exhibition were pulled solely from the Met’s own collection in New York – a constraint that helped set parameters says McBride, noting that it is not a complete history of commercial photography – and most of the pieces have rarely been publicly exhibited. The curator was keen to rectify this, she says, and moreover she was curious to unpack their role in shaping the visual language of modernism, as the show endeavours to do.

'The Real Thing: Unpacking Product Photography’

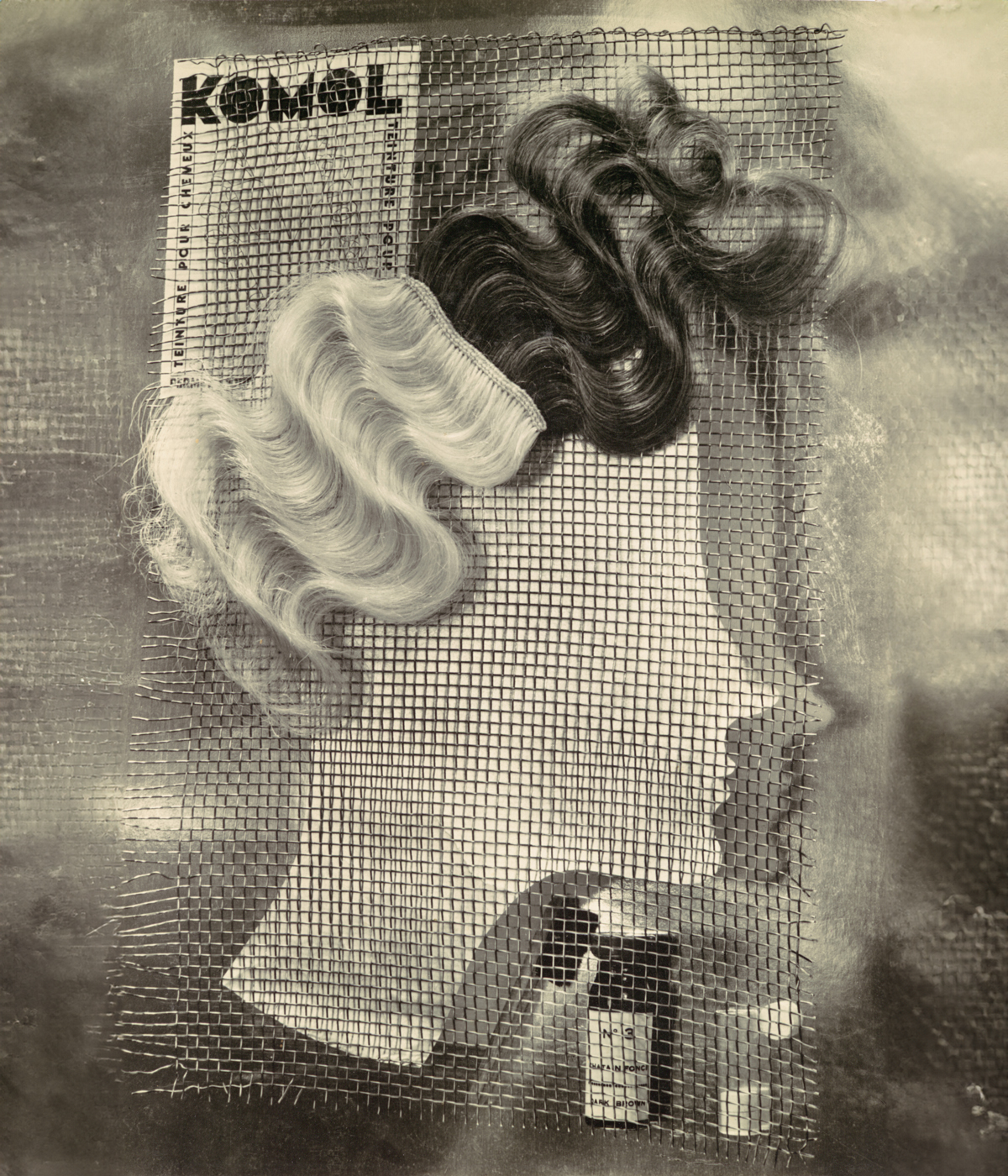

‘I was interested in going back to the source material, the trade catalogue, and was struck by its own sort of modernism. Looking at the way it presents these objects for sale, and thinking about the relationship between avant-garde aesthetics and this more applied set of circumstances and commercial priorities, and how they talk to each other,’ she says, relaying the show’s earliest genesis. ‘The photographers in this exhibition reanimate objects that are not usually of great cultural value – the tube of toothpaste or the fork on the table for example – showing that these can be subjects not only for commerce, but for artistic reverie.’

Mapped out in categories in what McBride describes as an ‘episodic romp’, wall labels bear titles such as ‘The Inventory’ and ‘The Unfamiliar Thing’, foregrounding work by celebrated photographers like August Sander and Paul Outerbridge, as well as lesser known artists including Hampson. The work is predominantly monochromatic, with gelatin silver prints, daguerreotypes and ambrotypes all featured, but viewers are also made privy to early colour work, such as in ‘Worth Reaching For’ by Anton Bruehl for Kentucky Whiskey distillery Four Roses; shot in 1949, its hot air balloon scenario was constructed with the help of miniaturists, set dressers and a celebrity florist.

Visually anchored in a previous time, the show’s sensibility is largely informed by a more contemporary moment, says McBride. ‘Product photography is, now, completely inescapable – it follows you around and stalks you on social media – and that condition is very interesting,’ she asserts, reflecting on the modern commerce landscape and this relationship between the past and present. ‘It obviously informs a viewing of the historical material, and so I wanted to look at how we got to the place we are now in; what conventions informed these current circumstances.’

Echoing one of the most famous taglines of the late 20th century, the show’s moniker was employed as a nod to the concept of truth in advertising and its significance for photography specifically. ‘I wanted to engage the language of buying and selling, and that slogan seemed particularly apt to invoke the dialogues around the history of photography,’ says the curator. ‘The promise of photography, from its earliest days, was that it shows the world in an objective way – of course, we know now to question those claims – but “The Real Thing” seemed an inappropriate wink at this narrative of photographic truth.’

Further observations of this play on reality occur throughout the exhibition. André Kertész’s ‘Fork’ (1928) for example, shot on a whim at a friend’s dinner party, would later be acquired by a German silverware company: the fork it appears to advertise was in fact from a French department store.

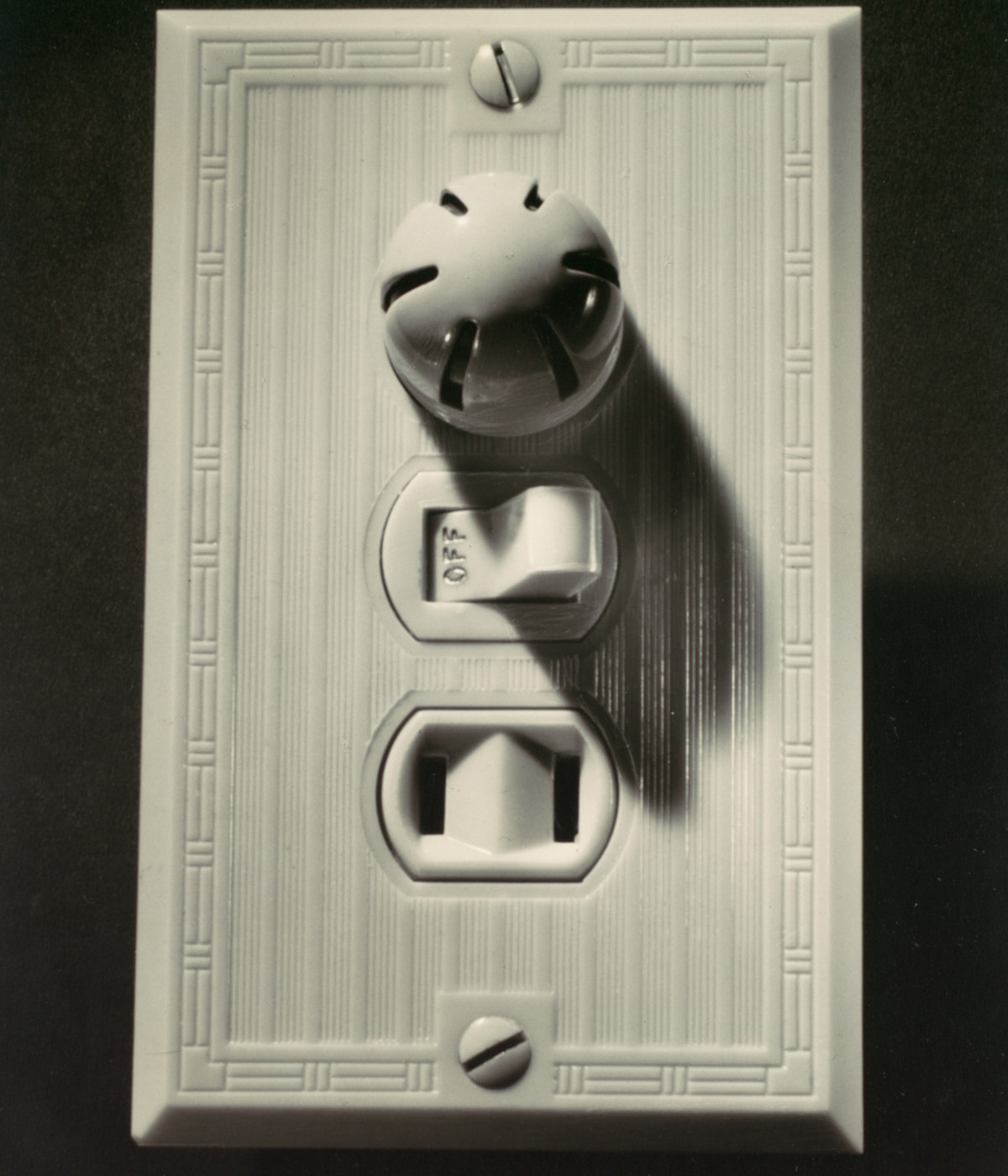

‘Part of the show explores “The New Vision”, and how photographers in the 1920s and 1930s, especially, were using the camera to transform the ordinary world via unexpected angles, or surprisingly oblique perspectives to make the known world unfamiliar,’ explains McBride. ‘That impulse persists today, while the innovations of this first century of product photographers plays out constantly in contemporary photography. People assume Photoshop and digital photography transformed the nature of the medium, but retouching and manipulation goes back to the earliest history of the medium.’

‘The Real Thing: Unpackaging Product Photography’, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, is on until 4 August 2024