Out of all the surprises “Squid Game 2” yields, the most bizarre may be the love/hate attraction to Thanos, Choi Seung-hyun’s lavender-haired, pill-popping hooligan.

Player 230 – real name Choi Su-bong – is the mascot for every would-be alpha whose inflated sense of specialness is precisely what makes him ordinary. In the “Squid Game” dorms he’s just some guy with a douchey haircut until another player recognizes him from TV or the Internet, awestruck by his showing as the runner-up in the final round of a show called "Rap Underground." Not the winner, the also-ran.

When it’s revealed Thanos’ 19 billion won of debt is the result of buying into a cryptocurrency scam, that tracks. He’s that deadly combination of shallow, narcissistic and unable to accept responsibility for his actions. He says "bro" unironically. His cheeseball flirtations open with him calling women “señorita” (but . . . why?). Before the killing begins, when other contestants are asking why they were kidnapped after agreeing to participate, he takes his time to complain about his fit.

“What’s with these shoes?” he asks a guard, holding up one of the generic white slip-ons everyone's wearing. “My shoes are limited edition! They’re hard to find! Are you going to replace them if they get ruined?”

His B-level talent is enough to earn him the fame he's incapable of gaining by way of his craft — and his lyrical skills are pure yikes.

“Red, orange, yellow, green, I’m a legend, Thanos . . . look at us in the blue-green, now give me the green light,” he freestyles to some slow-blinking bunny more concerned with looking cute than staying alive before “Red Light, Green Light” kicks off. Then he delivers the clincher line in English while flourishing a finger-heart: “I like . . . you.”

Moments later, when her brains are splattered across his face, he realizes he's just another face in a cheap crowd of death targets. Instead of that epiphany humbling him, it's emboldening, goosed by a dose of chemical courage gleaned from the cross-shaped pharmacy around his neck. Thanos shakes off this incomplete pass and barrels forward.

When the people around him nervously freeze for fear of being gunned down, Thanos skips and leaps. The killing floor becomes his playground. He stretches his arms wide like a child in the throes of a sugar rampage, pushing groups of strangers to their deaths, grinning as snipers take them out. It is difficult to say whether his ego or the drugs make him feel more invincible. Since he’s perpetually high, why not both?

“Squid Game” creator Hwang Dong-hyuk constructed his dystopian story around the universally relatable despair of indebtedness and desperation. Perhaps the sheer existence of Thanos is his underhanded acknowledgment that people don’t like to think too deeply about the moral of the story. It’s too real, too depressing. The brazen death spectacle seizes our attention instead — the more cartoonish and brutish, the better.

Hence this second-rate rapper playfully rendered by one of South Korea’s best hip-hop artists — Choi, who performs by the name T.O.P.

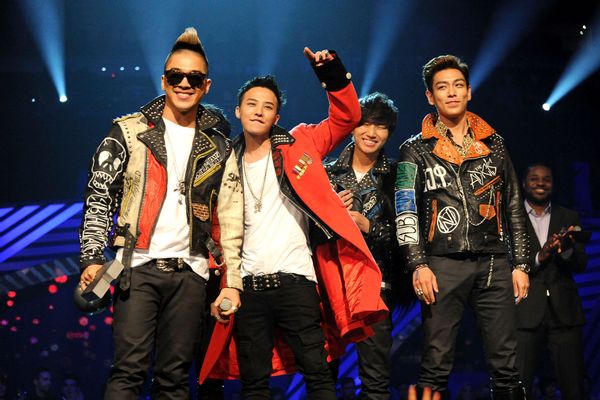

Choi spent most of his career with the K-pop sensation BigBang. But in 2017, he pled guilty to using cannabis, which is still illegal in South Korea. He received a 10-month suspended jail sentence and retreated from performing – by choice, possibly, but likely by necessity.

“Squid Game” represents the artist’s comeback and a risky one at that. The show’s international audience can’t help noticing Thanos for better or worse, but most reactions have been appreciative. South Korea’s audience is not as amused, taking issue with the character’s copious drug use and shocked that a star who copped to using drugs in real life would play a drug-abusing party predator in a globally popular TV show.

Choi isn’t trying to divorce his reputation from his characterization, even if the actor has said his goal was to deliver a performance that’s as realistic as possible. T.O.P.’s fans have caught the winking references to his real-life stage persona and this bizarro version Hwang wrote for him, down to pausing when he forgets the lyrics in the scene described above.

The real artist halted at that moment, embarrassed to have lost his flow. Thanos never had one; he’s all style and flash, and that’s more than enough to make it on a two-dimensional screen.

But the character works because of the actual performer’s sense of knowing. Artists can sniff out genius from fakes, and Thanos sure looks like a parody of a pretender T.O.P. has encountered in the wild.

Perversely, though, the moment that really adds the villainy to Choi’s shoddy wordsmith comes in the fourth episode when he tries to work his plastic charm on Player 380, Se-mi (Won Ji-an). Thanos, the Internet-bred Alpha male flanked by two sad little hype men, steps up to the young woman with facial piercings and a don’t-mess-with-me attitude, expecting to be worshipped. She sees him for what he is and plays him right back.

Ultimately their psychological games don’t work out in either of their favor – each is eliminated, although Thanos earns the forked-up ending he gets.

But their chemistry sparks because of what each represents. Thanos is the manosphere, the embodiment of the sexism permeating every sector of South Korean society (and, indeed, much of the world). South Korea has the widest pay gap between men and women among the nations monitored by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Women are persistently discriminated against and targeted for misogynistic violence and violations such as deepfake porn.

Se-mi responds by donning the Gillian Flynn Cool Girl’s mask, feigning enough interest for Thanos and his boy to think she’s playing to get when in truth she’s stringing him along until he’s no longer useful to her. Once Thanos realizes he can’t control Se-mi he turns his other male teammates against her. But, like every addled maniac, his hatred lacks focus. If he can’t take out his rage on Se-mi, maybe the pregnant girlfriend of the man who swindled him will suffice.

“Squid Game”’s explosion as a worldwide phenomenon can be attributed to a variety of factors. Some, like the giant killer doll robot from “Red Light, Green Light,” are singular and inimitable. Anyone can put on some version of its players’ green athleisure wear and be recognized as a player which, if the show’s scenario were real, is all most of us would qualify to be.

The greatest difference between the first and second seasons of “Squid Game” is the broader range of individual personalities. Hwang wrote more extensive backstories for his secondary ensembled players, more reasons for the viewer to invest in them as people instead of just numbers.

Thanos, however, doesn’t have much mystery to him because we know his type. Go anywhere on the planet and you’ll recognize him as a problem from across the street – the propped-up Andrew Tate wannabe with no substance underneath the sparkle and empty assurances.

Choi plays him accurately enough to rankle his home country’s audience, and believably enough to earn the rapper new fans in the U.S. and elsewhere. The hope is that they’ll be more impressed with his real persona than the unhinged supervillain he created. Given what “Squid Game” theorizes about fan worship, not even that is a certainty.

"Squid Game 2" is now streaming on Netflix.