Something was bugging the French president — a small line in a draft bill about Romanian physiotherapists. The paragraph that caught Emmanuel Macron’s eyes a few months ago stated that a lack of response from the French regulator would mean the rejection of any foreign practitioner’s application to settle and work in France. Macron knew the inertia of the government all too well. The clause could become a protectionist tool that would go against his Europhile principles. So he requested further technical assessment. Civil servants were stunned. “We don’t expect that level of detail from a president,” one said.

Such attention to minutiae lies at the heart of a presidency that has emerged as one of the most centralised and technocratic in French postwar history. From his corner office overlooking the gardens of the Elysée Palace, the youngest French leader since Napoleon is running a tight operation designed to exert maximum control over his government, parliamentary majority and party. Surrounded by a handful of trusted aides and dozens of millennial, mostly male, staffers, Macron is rolling out his economic plan, overseeing every element of its execution, shaping France’s diplomacy and concocting minutely choreographed communications coups. Rarely in the history of the French republic have decisions lain in the hands of so few — or so young.

Since his election in May last year, this concentration of power, compounded by a weakened political opposition and docile parliamentarians, has enabled Macron, 40, to push through contentious pro-business reforms at a rapid pace. As populist voices elsewhere grow ever louder, his reformist zeal, liberal activism and Gaullist pomp have changed France’s image abroad — from the sick man of Europe to a refuge for entrepreneurs.

“It’s a power that places efficiency at its heart,” says Virginie Martin, a political scientist at France’s Kedge Business School, of Macron’s approach to government. “It makes its own way, runs the state as a company and, for better or worse, has swept away debate from French political life.”

In a recent speech, Macron said: “One must be very free to dare be paradoxical and one must be paradoxical to be truly free” — and his self-proclaimed “ Jupiterian ” style fits neatly into this category. During the campaign, he appealed to voters on both the left and right by praising the “bottom-up” approach of technology start-ups, lashing out at the ossified political class and establishing a grassroots movement, En Marche. Today, though, even his earliest supporters are scratching their heads. Gilles Le Gendre, an En Marche MP, says: “Macron’s vertical governing style is incompatible with his promise of democratic renewal, which is by definition horizontal.”

When the youthful technocrat with a gap-toothed smile threw his hat into the ring in November 2016, reaching the presidency was a long shot. Macron had entered politics two years before, when François Hollande, the Socialist president, appointed him as economy minister. Until then, he was an adviser at the Elysée and not much differentiated him from other bright civil servants. Born to middle-class parents in Amiens, a northern town hit by deindustrialisation, he attended Sciences Po and ENA — the elite university gateways to the Parisian establishment, while also studying philosophy on the side. He spent three years as an investment banker at Rothschild, where he developed a network of corporate allies, a taste for bespoke suits, globish financial jargon and a habit of working round the clock — features he has since transposed to the Elysée.

As a minister, Macron caused controversy by taking swipes at sacred socialist cows including the 35-hour work week, and by fighting the Socialist majority to extend Sunday trading. His marriage to Brigitte, his former high-school drama teacher and 24 years his senior, became tabloid fodder. But extraordinary circumstances during the presidential campaign, including a financial scandal that ensnared François Fillon, the frontrunner, helped his cause. The political rookie qualified for the run-off round of the election with 24 per cent of the vote. Two weeks later, he defeated the far-right candidate, Marine Le Pen, by rallying mainstream voters. “I am the product of a form of brutality of history, I broke in because France was unhappy and worried,” he told the press in February.

Macron declined to be interviewed for this article but, according to multiple senior aides, government officials, former campaign staff, parliamentarians and friends interviewed by the FT, he arrived at the Elysée with both a plan and a method of executing it. He is determined to liberalise France’s economic model, restore its international standing and profit from a globalised economy undergoing rapid technological change.

His approach: a blitzkrieg of legislation. “A sense of urgency dictates the need to carry out reforms in all directions simultaneously and very fast,” says one senior presidential adviser who warns that voters should not expect the pace to slow down even if that means eating away political capital. “Taboos won’t stop us.”

Macron’s election is like Hiroshima year zero. A nuclear bomb fell on French politics and we’re still standing in the rubble

At stake is whether Macron will succeed in relegitimising the postwar liberal consensus in the eurozone’s second-largest economy and, by extension, help contain the populist onslaught on the EU. Surveys suggest most voters back his reforms. Yet his overall approval ratings have fallen below 50 per cent this year. A poll released for the first anniversary of his election showed that Le Pen and far-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon would each get about the same share of the vote as in last year’s presidential polls. The president siphoned off wealthy, urban and highly educated voters from mainstream parties with a platform intended to redraw political faultlines. But it’s still unclear whether he will be able to lure the working class away from the extremes.

“Macron’s election is like Hiroshima year zero,” says Laurent Bigorgne, head of Paris-based think-tank Institut Montaigne, who helped set up En Marche. “A nuclear bomb has fallen on French politics and we’re still standing in the rubble.”

The president’s style of governing is forceful and decisive, quick to combat dissent. This was demonstrated when, two months after the explosive 2017 election, top business executives gathered in Aix-en-Provence. A few days earlier, Prime Minister Edouard Philippe had suggested in parliament that Macron’s planned tax breaks for investors and businesses would have to be delayed in order to reduce the French deficit.

Finance minister Bruno Le Maire, who — like Philippe — had defected from the centre-right Republican party to join Macron, openly criticised the delay, according to a member of the government. He pushed for slashing the wealth tax even if it meant widening the deficit and causing yet another row with Brussels, according to finance ministry officials. “We can perfectly reduce public spending . . . and at the same time cut taxes,” he told reporters in Aix-en-Provence.

Philippe and Le Maire were summoned to the Elysée the following morning, where Macron was waiting with Elysée secretary-general Alexis Kohler, his trusted number two. According to people who were there, Macron laid down the law, telling the men that all his promised tax breaks would have to be passed in 2017 while the country would also meet the EU deficit rules. He also told them to stop blathering in the press.

“That was gutsy. No one knew if growth would be sustained enough to make it work,” says budget minister Gérald Darmanin, who was also in attendance. “But the president was right. Delaying would have had a negative impact on [business] confidence. Fulfilling the pledges had a positive one. It was a good political lesson for me.” Last year, France’s deficit fell below the 3 per cent EU limit for the first time in a decade.

The Macron-Kohler double act is an important part of how the president does business: through a number of powerful lieutenants. “Every time we see the president, Alexis Kohler is there,” says a ministerial aide. An ENA graduate like the president, Kohler is sometimes described as his twin brother and it is his job to execute the presidential programme. Many see him as the effective boss of Bercy, France’s mighty finance ministry. Kohler keeps a firm grip over the administration, which he knows inside out and where he can make or break careers. Over 50 advisers report to him, a dozen of whom are shared with Philippe and attend all meetings arranged by the PM.

Looking guarded in a grey suit, Kohler tells the FT that this set-up is intended to avoid divergences of views. His role, he says in a soft, cautious voice, is “to deliver” and “make sure we do what we said we would do” — a mantra repeated over and over in Macronist circles. “In France, people had gotten used to leaders who would start their term with an audit and end up changing their plans six months later,” he adds.

Only the Green Room — named for its olive tablecloth and curtains — stands between Kohler’s corner office and that of the president. He says the appointment of specialists, rather than politicians, to some of the most important ministerial jobs — labour, education, justice, health — has brought “legitimacy” and “efficiency” to their reforms. It has also brought loyalty to the president: during weekly meetings, officials say that Macron likes to challenge these government novices who owe him their jobs. They must also send their speeches and interviews to both the Elysée and the PM’s office for review. While the French press typically allows political interviewees to check their quotes pre-publication (not a practice generally accepted in the UK), Les Echos, France’s largest business newspaper, recently refused to publish an interview with the minister of transport, because it had been rewritten beyond recognition.

In previous governments, the number of advisers hired by ministers had swollen into the dozens — typically because they wanted to keep their personal political ambitions close to their chests. Macron and Kohler decided to limit the number to 10. “Like in any large corporation, we decided to cut down the thick layers,” Kohler explains. “We want to empower the administration. Either you trust them and you use them, or you don’t trust them and you change them.”

Macron expects similar loyalty from MPs, most of whom are first-timers, and from the party, now rebranded La République en Marche — republic on the move. “We created a very clear and coherent political platform and a structure to help it win,” a senior presidential adviser says. Old mainstream parties including the Socialists, who were decimated in the last election, started to break away from their leaders because of “disagreements, different currents”. “There’s none of that at En Marche,” he says.

A close aide says Macron, who sleeps four hours a night, “had always had a tendency to control everything.” Other officials insist such authority is necessary at the beginning of the presidency. “One needs to be Caesarist or Bonapartist, then you can let go a little at a later stage,” says a ministerial aide close to the president. Macron himself recently told literary magazine New French Review: “I own the choices that are made, I hate the habit of explaining the rationale of a decision: there’s a time for deliberation and a time for decision. They cannot mix.”

“[Under Hollande] we were running all day long to stay in the loop,” recalls a former Elysée aide who worked with Macron then. “We were in constant crisis mode, fixing things at the last minute.” Ministers competed against each other and double-crossed the PM. “Decisions would be overturned, and overturned again,” says another aide. “The worm was in the apple from the beginning.”

Yet there are downsides to Macron’s methods. Staff describe his style of leadership as one that has become so paranoid about rebellion that it exerts excessive pressure and quashes debate. Short-staffed and sleep-deprived advisers struggle to compensate for their ministers’ inexperience. An official in one ministry says the centralised organisation “tends to create bottlenecks at the Elysée”. When Kohler does make a decision, few dare to appeal it even if they think it is wrong.

Political game-playing is now frowned upon partly because Macron would not have reached power without it. “We’re best placed to know how quickly the balance of power can shift,” a government adviser says. In 2014, Macron resigned from his job as economic adviser to Hollande because he had been refused a promotion. A few weeks later, he was offered the economy ministry but he soon grew impatient and began plotting a presidential bid.

One Saturday in December 2015, he invited a dozen of his closest advisers for lunch in his apartment, where they discussed possible movement names. En Marche was most praised, according to a person who attended. When the party was launched four months later, Macron assured Hollande that it was meant to help his re-election. After his first political rally in July in Paris, he insisted he had no intention of running for president. “Grotesque. Kisses,” read his text message to the Socialist leader, who published it in a revengeful book released last month.

Meeting Macron back then was a revelation for Stanislas Guerini. Now a Paris En Marche MP, the 35-year-old had been part of a group who worked for Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the former Socialist finance minister who sounded the alarm about France’s dysfunctional social mobility a decade before Macron — and whose own ambitions were ended by a sex scandal in 2011.

Macron said, “Stop taking into account external constraints.” We had found someone who could serve as a detonator’

Guerini recalls that Macron initially wanted to create a foundation, as he dislikes parties as institutions, but his advisers pushed him to create a more structured political platform. Meanwhile, Macron urged them to get rid of their old mindset. “Our experience [with DSK] had taught us that the world was blocked by others; Macron would say, ‘Stop taking into account external constraints,’” Guerini recalls. “I thought, ‘Wow, this guy is ready.’ We had found someone who could serve as a detonator.”

Guerini’s best friend, Ismaël Emelien, who oversees communications and strategy at the Elysée, was another DSK boy instrumental in Macron’s presidential plans. The “special” adviser, 31, was sent by Macron to set up En Marche and witnessed its initial membership surge. On a bookshelf in Emelien’s fourth-floor office — which Macron occupied a few years ago — sits a portrait of the president holding his fist up during a campaign rally.

For Macronists, communication is as essential as execution. While Kohler whips the government into action, Emelien, a taciturn former public-relations executive with dark-rimmed glasses, makes sure the French public knows about it, an aide explains. “Alexis Kohler is the brain, Isma is the one who thinks out of the box,” says Jean Pisani-Ferry, the economist who wrote Macron’s economic programme. On June 1 last year, when Donald Trump announced his decision to withdraw from the multilateral climate change accord signed in Paris in 2015, Emelien and Macron met to brainstorm a response — short videos in French and in English, according to two people with knowledge of the meeting. On the spur of the moment, the adviser suggested ending with “Make Our Planet Great Again” — a pun on Trump’s “Make America Great Again” that was irreverent enough to signal Macron’s disagreement.

After testing it with a friend outside the Elysée, the president decided to use it despite possible diplomatic repercussions. The video went viral on social media and became a rallying cry for US environmental activists and companies. The next day, Macron’s diplomatic advisers were at a loss, say aides. They feared plans to invite Donald Trump for Bastille Day celebrations the following month would be jeopardised. “We let a few days pass,” one recalls. But Macron’s move did not alter his relationship with the US president — and even seemed to elicit his respect. Macron added a handwritten note at the bottom of the formal invitation, which, much to diplomats’ relief, was promptly accepted.

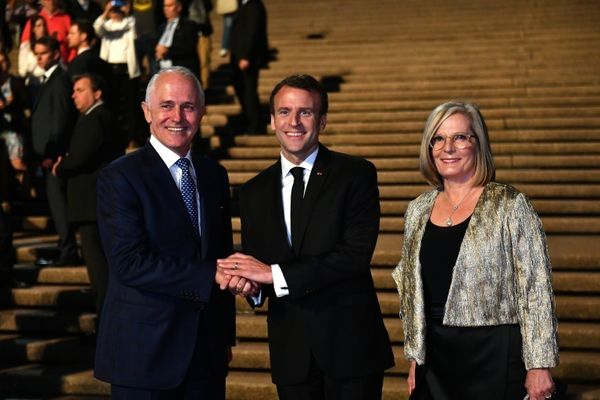

Last week, Trump returned the favour by hosting a three-day state visit for his French counterpart that was marked by displays of affection between the two men, including much cheek kissing, hand-grabbing and back-slapping. The trip was yet another testament to Macron’s interpersonal skills with older politicians such as Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, Hollande or the late Socialist PM Michel Rocard.

If you ask him, Emelien refuses to confirm he had the idea for the climate change video ending. Like Kohler, he is the epitome of discretion. Aides say he is in charge of nothing and free to meddle in everything. He and Guerini are part of a group that regards itself as guardians of the Macronist promise, which a top Elysée aide describes as “giving individuals the ability to choose their lives by themselves”. Guerini sums it up as a project to reignite “social mobility” centred on “the values of work, the EU, freedom as much as equality, and benevolence”.

The hard part for Macron is convincing French voters to embrace a more flexible economy, just as many are demanding more trade barriers and feeling threatened by Muslim immigration. The historian Jean Garrigues says: “There is no Macronism without perpetual movement because its justification is that France has been paralysed for 30 years. Macron senses there’s a historic opportunity, enabled by his own political transgression, to help France transition towards a more globalised, automated and flexible society.” The bulk of his reforms have centred on making the labour market more flexible, improving workers’ skills and reducing discrimination in the workplace. “The notion of work is central to Mr Macron’s programme,” a close aide says.

Macronism is a form of corporate management applied to government. Ministers and parliament have little clout

But, by the president’s own admission, those reforms will take years to significantly lower unemployment, which remains stuck at nearly 9 per cent of the workforce, higher than the eurozone average. The risk is also that these reforms are perceived as mere alignment with other countries. Meanwhile Macron’s grand plans to overhaul the EU to make it more protective of its workers and focused on boosting growth are running into typical Brussels inertia and German prudence. “For now, we’re not in an innovative phase,” reckons Mathieu Laine, head of London-based think-tank Altermind, who says he regularly exchanges messages with the French president in the dead of night. “He will have to outline a wider long-term vision or else he could end up like Matteo Renzi.” The former Italian centre-left reformist prime minister, who reached power in 2014 aged 39, lost to populist parties from the right and left in general elections in March.

Because many of Macron’s early measures — including a flat tax on capital gains and lower taxes for the super-rich — are inspired by supply-side theories, they are mostly seen as tilted to the right. A recent bill toughening asylum-seeking rules and legislation boosting police powers to fight terror have reinforced the perception that he leads a party of law and order. A close aide says this is “factually wrong and unfair” — the remnants of an old cleavage soon to be made extinct by a political revolution of which Macron and En Marche are “both the catalyst and product”. But even loyalists such as Guerini say he will have to outline a plan for the “most vulnerable” in the second phase of his term.

One year on, Macron’s election has failed to eradicate public defiance towards politicians. More than eight out of 10 French voters say the political class does “not pay attention to what they think” while more than two-thirds say they are “in general corrupt” and “look after the rich and powerful”, according to a wide-ranging survey by Paris-based research institute Cevipof in December.

“Macronism is a form of corporate management applied to government, it’s a system where ministers and parliament have little clout,” says Luc Rouban, political analyst at Cevipof. “[It] doesn’t address the disconnect with the working class. Blue-collar workers, who voted in larger proportion for Le Pen, are not drawn to Macron. Anger is still there. En Marche doesn’t have a network of local elected officials across France and the risk is that this leadership gets even more disconnected.”

Cracks are also beginning to appear in the Macronist galaxy between the Elysée and its satellites — the En Marche MPs and party members — as the constant flow of bills rattles unions. Last month, 15 En Marche MPs (out of 312) defied party unity by abstaining or opposing the government bill on immigration because they judged it too tough (the far-right National Front backed some of the more restrictive clauses). Over time, rifts are likely to widen within the disparate group of MPs. About half of the 200,000 or so “marcheurs” who helped during the campaign have become inactive.

Some, like Sarah Oliviero, a Paris entrepreneur, say they are content to have given a hand to get Macron elected and are not looking for more. Others feel left without a proper direction or are disappointed by the centralised organisation of the party. “There’s no local structure, no willingness to structure it,” says Charles Delavenne, a lawyer in Lille, northern France, who sits on the party’s national committee. “The movement brought one man to power, but the whole idea was to feed the presidential project.”

Even the most loyal foot soldiers wonder if Macron is willing to build a movement that will outlast him. Guerini says: “Macronism is not just a method. We need to work out exactly what our doctrine is, we need a sort of tool box that will help us define the Macronist answer to issues beyond the presidential programme.”

A close aide to the president reckons that “if Macronism is perceived as a form of pragmatism then we are in trouble . . . We are not going to solve everything by reducing unemployment. We need to address the question of identity, religion, secularity,” he says. But this would involve allowing En Marche to free itself from its creator — and for now, Macron and his Elysée crew do not appear inclined to let go. “We’ve done everything the wrong way round,” Le Gendre, the MP, says. “We started with a presidential programme without building a proper doctrine. It’s all about the intellectual vision of one man.”

Anne-Sylvaine Chassany is the FT’s Paris bureau chief

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2018

2018 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.