An author laughs through her tears in an interview ahead of her appearance at the Auckland Writers Festival This just in from Hong Kong. Its chief executive has corrected the language of a journalist for asking a question at a press conference about the pro-democracy protests of 2019: "First of all, it is not [called] the 2019 protests. It is the black violence." And: a 23-year-old has been charged under the Beijing-imposed national security laws for allegedly “intimidating the public in order to pursue political agenda". He was attempting to stage a protest, otherwise known as a black violence. Also: a satirical cartoonist has been sacked after a government official complained about a drawing that mocked local elections, and his books were removed from libraries. When approached by the last signs of independent journalistic life in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Free Press, the Leisure and Cultural Services Department commented, "Books that are suspected to potentially violate national security law will be immediately removed for review."

Scary, pathetic, not sane - it's just the way things are now on the island. Hong Kong is still beautiful, still exciting to visit, still an amazement of good food and bright lights, but no longer free in any sense. I went there in March to attend the Hong Kong international literary festival. Of course I covered the literary festival but of course I covered the central event of life in Hong Kong: China, and China's control. The stories were notes and observations from eight days and eight nights. Louisa Lim, about to appear at the Auckland Writers Festival, is the author of the deeply felt, innately knowledgeable book Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong. She grew up there. She was a journalist there during the 1997 handover. She left and may never return there.

Its dedication page reads, "To all those who really fucking love Hong Kong." Lim really fucking loves Hong Kong. Her book is a cry of despair at what has been lost, and includes a rousing passage about hope, about Hong Kong regaining a sense of its own destiny - but she finished writing the book in 2021. I interviewed Lim ahead of her festival appearance this Friday, chaired by Newsroom supremo Sam Sachdeva. The first thing I asked was what has changed in Hong Kong since she finished the book, and the first thing she said was: "I would say things have got a lot worse."

She meant the apparently unlimited power and reach of the national security laws, with 47 activists and journalists in jail or on bail awaiting trial. She meant changes to education, where children are required to salute the Chinese flag. She meant changes to local elections, which have effectively gutted the city’s last remaining democratic institutions, as mocked by the cartoonist whose work has been made to disappear. She meant all manner of things, including changes to that first line of defence always attacked by new masters – language.

We spoke over the phone. Lim teaches at university in Melbourne and was late for a class; it may be one of the reasons she spoke so fast, with a habit of changing the course and direction of a sentence, but I suspect her passionate and emotional answers would have been evident in any circumstance. She said, "It’s weird the way people use language has changed. The phrases that officials use have become very similar to the phrases used in mainland China. In the past Hong Kong was quite separate from China but now its becoming far far closer."

I said, "Are you describing forms of bureaucratese?"

She said, "That’s exactly what I am talking about. Mainland slogans have been adopted. One example. When we talk about media freedom - in the past Hong Kong media has been pretty boisterous, and cacophonous, but since the national security legislation came in, 12 news outlets have closed down, and the directive from above is, 'Journalists should tell a good Hong Kong story.' That's a real echo of journalists in China who have long been told, 'Tell a good China story.' And so journalism in Hong Kong is no longer acting as a monitor of those in power, it’s acting really as a megaphone to guide and channel public opinion, and taking a much more Marxist role than a Fourth Estate role."

I said, "But the exception surely is that thing of wonder, the Hong Kong Free Press."

She said, "The Hong Kong Free Press is very careful with what they report on. I think they tread a very very thin tightrope in order to continue to exist. If you look at some of their more political reporting they will take it from AP and other outlets. But you're right. They are fantastic, and they're doing their own original reporting as well. We need these independent voices because they are being crowded out and it's really hard for them to survive."

Much of her book Indelible City is an investigation into Hong Kongness - the character of the people, the history of the island, its values of determination and independence. But now it's as craven to the one-party state as any another province of mainland China. I asked, "Is there even any such a thing as Hong Kong anymore?"

She said, "I think the city still exists but we are seeing an assault on Hong Kong, which is really an assault on Hong Kongers, on identity, and it's an assault on history as well. China is even saying Hong Kong was never a British colony, even though there are roads and parks named after British governors and Queen Victoria," she laughed, "but their argument is that China never accepted these treaties from the 19th Century that ceded Hong Kong to the British, and argues Hong Kong was more like an occupied territory than a colony, that it was never a colony. But that too is an assault on history and identity because in rewriting the past you are chopping away at an identity that Hong Kongers have constructed for themselves."

Lim casts Hong Kong in her book as a kind of bystander in its own modern history, passed like a parcel between China and Britain. It's now in the firm possession of China under the One Country, Two Systems paradigm. I said to her, "The reality is that China took control in 1997. Isn't it simply being administered just like any other province?"

She said, "I don’t think so because the kind of laws, and the kind of restrictions that it's under are far harsher than the rest of China. One of the problems is that nobody really knows where the red lines are. In China, if you're a dissident, you probably know over the years what you can say and what you can't say, what will get you ended up in a prison cell and what won't, and you can make a reasonably educated guess where the red lines are. But in Hong Kong the red lines are everywhere and nobody can see them. Sometimes people talk about a red sea. The kind of cases we've been hearing about in the past year have been quite crazy. Kids who get in trouble at school because they didn't - they supposedly disrespected the flag at a flag raising ceremony. All this very very draconian application of national security laws, and I think the overall goal is to instil fear in the population."

Lim writes in Indelible City, "There has been an accelerating slide into becoming a different city altogether." She described that slide in 2021; where has that slide taken Hong Kong in 2023? I said to her, "It doesn't look good."

She said, "No, it doesn’t look good for Hong Kong at the moment. So what we are seeing is so many Hong Kongers leaving. Tens of thousands have gone to the United Kingdom. They are fed up, and that is a trend which is going to continue. But I would say the strength of Hong Kong is the Hong Kongers themselves. They have a long memory. They remember the killings of 1989 in and around Tiananmen Square. Hong Kong took on that responsibility of remembering, and they remembered for the Chinese people who couldn’t publically remember. Hong Kong had these gigantic vigils every year. 150,000 people in a park with candles in silence. It really was an act - it had great symbolic power, and now I think for a while it will fall to Hong Kongers in exile to remember, and to keep those ideas alive.

"But I will also say it's very hard to predict what the future - it's such a black box itself, Chinese politics. We really don’t know - we have very little idea what is happening at the highest echelons of leadership. If things were to change there, then it could have an impact on Hong Kong."

I said, "How on earth would it ever change in China?

She said, "Mm. Yeah. So I think the short range forecast for Hong Kong is pretty grim."

Lim writes in her book, "The idea that Hong Kongers are purely economic actors has never been true." She states that two million people out of a population of seven million marched in pro-democracy protests - sorry, black violences - in June 2019. But the daily reality of Hong Kong is also people just going about their business, making a living, dating, going to school and church, eating good food…Politics is not necessarily a part of that. I said to Lim, "Maybe people are just happy and making the best of things. What's the reality, do you think?"

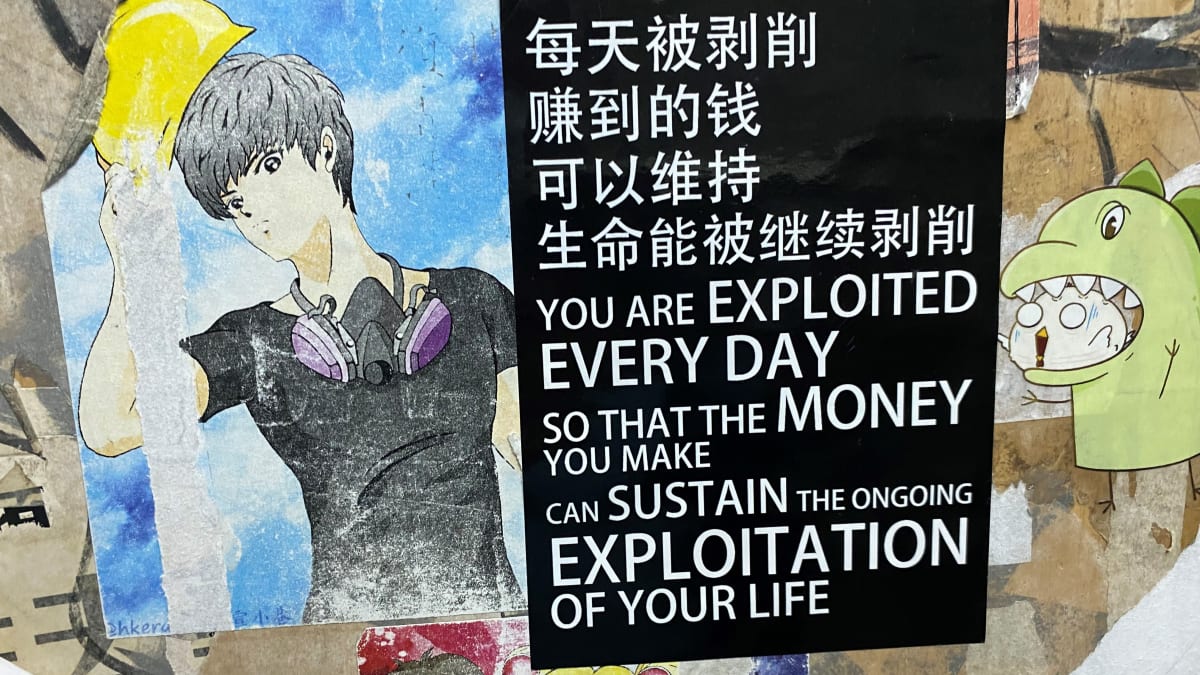

She said, "There's a portion of the population who are pleased some semblance of normal life has returned and people are no longer protesting. But there is also a portion of the population that once was highly political that no longer talks about politics. I just wrote a piece for the New York Times. It came out yesterday, and I've been getting so many messages - someone sent me a message they'd just been in Hong Kong and even though you couldn’t see any signs of the protests, if you started to look very carefully, you would see the signs if you knew what to look for, of pictures hidden in little cafés that had symbolism for people who understood. Very, very coded."

I told Lim that I went to a bookstore in Mong Kok and bought three seditious postcards, including an illustration of a figure giving a speech above a message that read, BEWARE THE ONE PARTY STATE. I said, "Is that an example of what you mean?"

She said, "It sounds like it is! These kinds of very small bookshops which have always been allowed to exist in Hong Kong - their continued existence is a good sign but it does not mean everything is normal. We are seeing a concerted campaign by Hong Kong government to really present Hong Kong as back to normal and that includes giving away hundreds of thousands of air tickets for free, and holding these kind of events like the literary festival that you went to. These are great events but they are part of that campaign."

I was somewhat incredulous about this claim. The festival was staged without government funding; it's always existed in Hong Kong as a non-profit, financed by private companies such as JP Morgan. I said to her, "Are you suggesting I was attending a coded propaganda event?"

She said, "How would I put it. I would say there is no such thing as soft power to the Chinese. Power projection is part of their toolkit, and writers and journalists are often a part of that. For years they offered journalists these tours to China and that would produce really positive stories about China, stories that often didn’t write about human rights abuses and political indoctrination or any of that stuff. But I don’t think - I don’t want to say the literary festival was a propaganda event, no."

The literary festival wasn't a propaganda event. But I was just passing through; for Lim, Hong Kong had once been home. Although her book is a terrific piece of journalism and history, its power is that it's a personal story. Hong Kong is meaningful to her, always will be. I said to her, "How are you thinking of Hong Kong now? With despair, maybe even with survivors guilt that you left?"

She said, "I feel sad that I left. It’s a city I call home. I always thought I would grow old there."

I said, "Woah."

She continued, "I feel really - I do feel even talking about it, like this, this great sense of sadness. But at the same time I know that Hong Kongers are a resourceful bunch of people, they're resilient, they're hard working, they're the world's best migrants!" She was laughing but it sounded like she was laughing through tears. She continued, "They will rebuild. They will build lives in Hong Kong communities elsewhere. Hong Kong has been through hard times before."

She had to go to teach her class but I had one more question to put to her, one last attempt to see if there were possibilities of hope and optimism in Hong Kong. I said, "Here's a thought. Maybe China itself exists as a source of hope. Are there signs or beacons of independent thinking, of liberty, of some sort of quality of life, within China, that could appeal to Hong Kongness?"

The short answer was no. It was a terrible attempt to contrive an upbeat, positive ending to our interview. She said, "At the moment I am afraid to say there is little hope from inside China. The atmosphere is increasingly oppressive there as well. Writers and historians have all been shut down. If we look towards China for signs of hope when it comes to intellectual freedom, there's not a lot there."

Louisa Lim will speak with Sam Sachdeva at the Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre, Aotea Centre, on Friday May 19 at 5:30pm. Her book Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong (Text, $37) is available in bookstores nationwide. The China Tightrope: Navigating New Zealand's relationship with a world superpower by Sam Sachdeva is published by Allen & Unwin on May 23.