Cyclone Gabrielle left a trail of destruction throughout Hawkes Bay. In the first in a two-part series on recovery in the region, Aaron Smale visited some of the marae communities that are picking up the pieces, including Omahu and Waiohiki.

It was a festive mood. There was a bouncy castle, free ice creams, a steady onslaught of food, and children laughing in the Hawkes Bay sun at the marae in Waiohiki.

But out of the blue sky a sudden downpour of rain appeared. Within minutes the carpark was emptied out and the laughter was silenced. The whole area was deserted.

Part two: The long tail of Cyclone Gabrielle: the mountains that roared

The devastation of Cyclone Gabrielle that had ripped through the small community had happened more than a month earlier but the trauma was still just below the surface. Any rain triggered an anxiety that made people panic and flee. Their homes didn’t feel safe anymore.

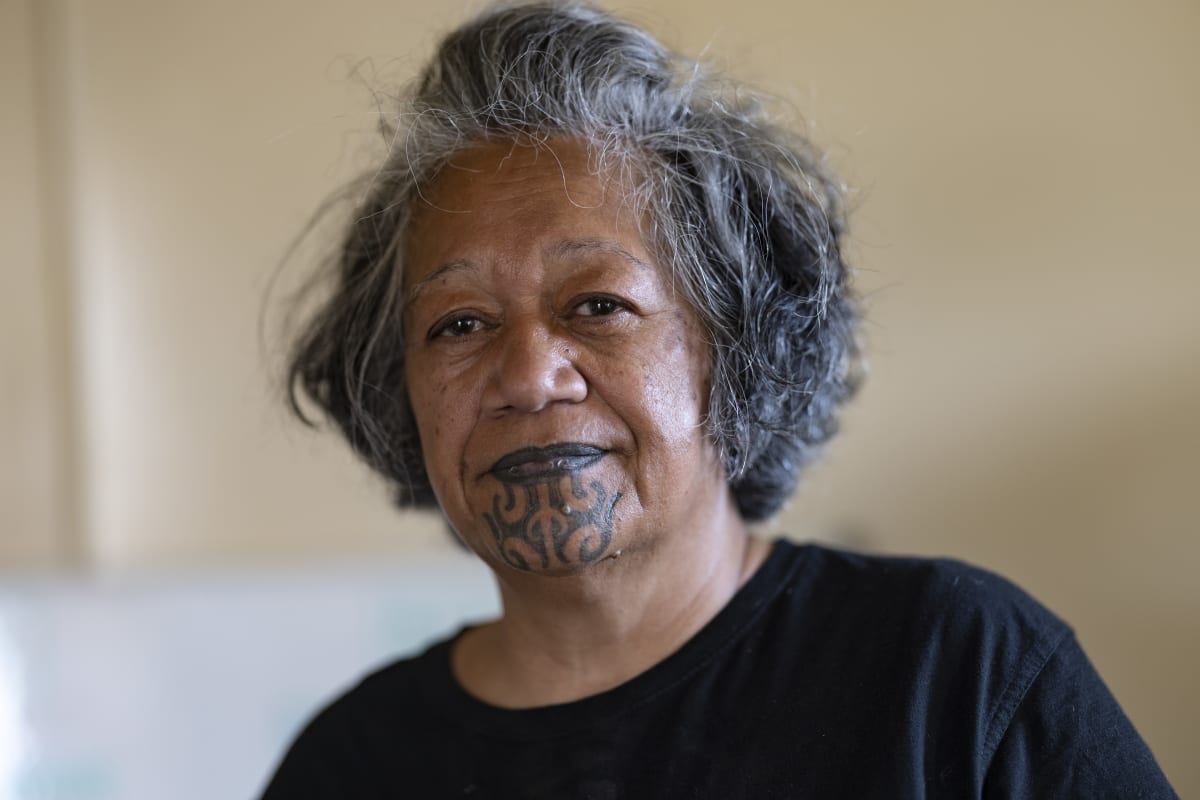

Kumeroa Samuels from Waiohiki said the recovery is going to take more than a clean-up of the silt and mud that washed through houses and upended lives. The emotional scars will take a lot longer to heal.

“This is the first day that some of our nannies have actually returned. And it's beautiful because it's on a better occasion. But I think that there's gonna be a lot of anxiety. You know, even just droplets of rain is going to cause a bit of panic and because of what they have lived through."

Some of the most severe damage in Hawkes Bay happened in the plain between the Ngaruroro and Tutaekuri Rivers which eventually converge near Clive on the coast. The rivers created a wedge-shaped plain and over Valentine's Day and the following 24 hours, multiple breaks and breaches along the banks flooded it with massive volumes of water in violent surges. That water inundated communities that were in that V – Pakowhai, Omahu, Waiohiki and others – were some of the hardest hit as the water barrelled through farms, houses, marae and lives.

Driving along the main highway between the rivers even weeks later there were surreal sights. Someone’s pillow hung up in a fence. Piles of apples rotting on the side of the road. Vehicles flipped and partially buried in the middle of a paddock. The silt was everywhere, similar to the liquefaction that menaced whole suburbs of Christchurch after the earthquakes. Viscous sludge when wet, dusty grit when dry.

While Cyclone Gabrielle has passed and the headlines have faded, the long haul to recover some kind of normality for many communities is ongoing. There’s winter to get through yet. Marae throughout Hawkes Bay that were the hub of their communities have become a rallying point of strength in Gabrielle’s wake, and not just for Māori.

Waiohiki is just across the Tutaekuri River from the Napier suburb of Taradale but the impacts are like night and day. Residents in Taradale were able to return to normal relatively quickly, while those directly on the other side of the river were still digging themselves out of silt weeks after the cyclone hit.

The Waiohiki Bridge trapped a mountain of debris – trees, a shipping container, water tanks – that was washed down the river and eventually busted the concrete structure, but not before damming the flow, which then spilled over the bank and inundated the community.

Samuels said that leading right up to the height of the floods people weren’t taking the threat that seriously, even making jokes. But then things got deadly serious very quickly.

“At about three, four o'clock we heard a big bang. And we assumed it was a power cut or something. But later on we discovered that it was actually a shipping container hitting the bridge. And at that time I started watching out and I saw cars coming in, seeing the white lights reversing. I was saying to my husband, ‘Something is going on'.”

Her sister Charla Hawaiikirangi was woken by a commotion.

“I woke up. The phone call was about six o'clock in the morning. We had no warning, no nothing. Phones, alarms weren't even going off, not even the Taradale fire station, their alarm system, nothing.

"By the time I went over to my neighbours', the water was at the second step. By the time I got back into the house to get my family out, it was up to the next step. So it rose pretty fast. We gathered all our gears or what we could carry, I had my daughter on this arm, my son on this arm holding his dog, and my auntie was in her 60s, in the middle of us ... the water was really fast, really loud. So we got up the driveway onto the road. And then we got pushed up against another fence. So we were there about half an hour, maybe 45 minutes and my uncle came and saved us on a truck.”

The truck then became a ferry between the houses that were going underwater and the marae which was on slightly higher ground.

“Uncle Bobo had a dumper truck, and he brought a load (of people) in and then he went out for another load. And he brought another load and and then he tried to attempt his fourth one, and he just stopped because by then it was gushing. But it was heartbreaking to stand here and see whānau right there. And I couldn't even help them. You know, like, waving, crying, trying to get them to come over.

"My neighbour next door they had a little two year old and she was so strong. She had a little coat on and sitting on the roof of the house, but it was her parents that kept calm.”

The marae had become a focal point, having drawn families back to the area after the community hall burnt down over 20 years earlier and a new wharenui was built. Now it has become a rallying point again, Samuels says.

“Regardless of where you go in this world, your waewae (feet) will always be firm in Waiohiki because the whare is still standing. So I would hope that that's the mindset moving forward, that our doors will be opened, not closed, that our whenua will be utilised for whānau because they are whānau.”

For all the stress and trauma the flooding caused, the residents still managed to find humour in what they’d been through.

“It's become an in-house joke that perhaps our tipuna (ancestors) are saying ‘How are we going to get our whānau back together? Right, let's chop them off at this end and this end and then chuck them on an island where they can't go anywhere’.

“Whānau are whānau, but you know, this auntie don't like that auntie and this cuzzie don't like that cuzzie but you got no choice. We're all in that one hub where you can't go anywhere.

“There is a cousin who I hadn't spoken to for seven years. The last time I wanted to punch him in the face. Then when I saw him, I was like, ‘Oh, I love you cuz!' After the scale of what we just experienced, it was like, put all your tiko (shit) to the side.

“Actually what is important is our people, it's us who are living. Somebody up there had a plan.”

While somebody up there might have had a plan, on the ground the plans had to be improvised. Some of the old people got a fashion upgrade thanks to whānau lending them clothes and medications had to be sorted, Hawaiikirangi said.

“Our whānau lost everything. They literally had the clothes on their back. Some of the aunties were walking around with Tupac jerseys from their mokos. A cousin was trying to coordinate a little pharmacy, ‘Aunty what medicine do you have? Oh, yeah, she needs a heart medicine.’ Like it was just trying to coordinate because our nannies forgot their medication for their heart, for their diabetes, for whatever else they have.”

For Bill Henderson there was a shock that the river he grew up playing in could be so ferocious.

“Our playground was the river. Our playground was the paddocks. Our playground was all the driveways. The original riverbed runs right in front of my house so eventually I suppose it just found its natural path.”

That pathway included the paddocks and driveways and houses surrounding the marae. Fortunately Henderson's house is on higher ground and is two-storey, so at the height of the flood he had around 50 people evacuated to his home.

"I was still a little bit blasé about it. I thought we were okay. It wasn't until I looked out the window and I could see all the flooding around that I knew it was quite serious. My sister lives next door on her own, so I rushed across to her place and I had to wake her up to get her out of bed."

He says going back to flooded houses after the water subsided was traumatic. The sludge at the back of her house was hip-high.

“We're still processing it, just never thought it would ever happen, not in my lifetime anyways.

"I do hear children talking about it to their parents. Some are a bit traumatised to go over bridges. Even when it rains they're cuddling their whānau thinking, is this going to be another flood Mum, is this going to be another flood Nan.”

Henderson says while the damage to those on the Waiohiki side of the river has been devastating, it could have been worse if it breached on the more populous side.

“The stop bank finishes about a kilometre up from here. We're sort of the sacrificial lamb. You've got 50 to 60,000 people living over there and I don't know the number here but it might be 5000 people.

"Councils do have to take responsibility for flood protection, so they've got to now make a decision going forward what's required to protect more of the community."

Like many spoken to, Henderson says the support of others in the community and from beyond Hawkes Bay is something he'll long remember.

"The community spirit and all the help that we've had from from organisations outside the area has been amazing. Man Up sent down 200 people to help us out and without them a lot of the work wouldn't get done. There's a lot of other contractors that helped us out that we are so grateful for. Even the people that supply us kai. There's an Indian couple that turned up here about every third or fourth day bringing mince and nachos or rice. It's that sort of generosity that's really just blown me away and hopefully we can repay them someday.”

Omahu

Just up the road in Omahu not even the dead were safe.

Many of the residents of the small settlement on the other side of the plain near the Ngaruroro River were also caught out by the sudden turn of events when the river burst its banks and surged through the community in the early morning.

Drone footage shot by Fernhill resident Dawson Bliss show the floodwaters bursting through the stop bank and overrunning Omahu village, including the church and burial grounds.

Meihana Watson, chair of Omahu Marae and the Ngāti Hinemanu and Ngāti Upokoiri me ōna Piringa Haūu Authority, had lived in the Omahu community his whole life. He had to be blunt with neighbours when the floodwaters started rising as many didn't comprehend the seriousness of the threat at first.

“The water had breached over the top of the bank and water was already coming into the marae grounds so a lot of people just freaked I think. I came down and said, 'What the fuck are yous doing here? Get out'.

“The water was quickly coming up into the marae area so I opened a corner gate because there was a whānau with a couple of young ones. I said, 'Just get across there, there's no water between the marae and the bridge if you go that way'.

"That first, say, six hours from nine to about mid-afternoon, it was kind of hard to understand what was happening."

At one stage there was water coming from not just the breach by the bridge but from breaches further up the river and the overflow from a nearby lake. Those trying to evacuate were unsure if it was safe to cross the bridge because the water was so high and they became paralysed by fear. But in the end they had no choice and had to take their chances crossing the bridge while the water roared underneath it. Trish Nuku was one of them.

"We pulled outside our driveway and we could see all our whānau down Taihape Rd in their vehicles all parked across the other side of the road. And everyone was just looking in awe at the water coming over the bank, like no one could believe what they were seeing. I just remember our street being lined with people standing outside their cars, looking at the bank, not knowing what to do. And it was a really, really scary moment because we've never been through that ever before. My Mum it was really sad watching her have to leave her home that she knew that potentially she might not return back to, just hearing her cry and seeing the faces on all of our whānau down that street not knowing what to do.

"So water is coming off the bank and then we get down to the crossroads and there's just chaos, people not knowing which way to go, not knowing what to do. There was water coming from every entrance point that you could think of here in our community. A few of us went around the roundabout a few times and then thought, bugger it, we've got to get out of here. So we drove through the flood, drove through all that water. That was really, really scary."

But when Omahu families returned, they had to brace themselves for what they would find. Keita Tuhi returned with others and there was silence as they crossed the bridge. But in the grief there was also an odd glimmer of hope, care of a toddler.

"We weren't talking to each other. We were crying together, just comforting each other. We cried for what happened to our home. Not trying to make sense of it or even trying to find an answer. So we remained silent for quite a while. And then our little mokopuna, she started laughing, giggling, like she was none the wiser. Does she really know what went on? Maybe she didn't. Maybe she did. But her little bit of giggling, we all felt that."

They found their houses inundated with water and mud and their burial grounds ripped up and their ancestors and loved ones scattered around in the silt and debris. Many of the issues the flooding has left behind will take months if not years to resolve or work through. Like many communities, Omahu residents were caught out by the suddenness of the floodwaters and the lack of warning from authorities. Watson said the damage was hard to comprehend.

"It was just like a battlefield had gone through here. It was a blowout of the stock bank that caused a lot of the grief and damage. I'm quite tall, around two meters, but that hole is more than two meters deep and that would have created a lot of the gush in the water coming out of the Ngaruroro into the community," he said.

Solly Rameka had left Omahu before the peak of flooding, heading to Napier to check on his mother. But as he drove he kept hitting police road blocks, one of which he ignored, to try to get to his mother. All the main roads ended up blocked and he took various routes to try to get through.

"So the first thing that came to my mind was going to check my Mum, because she lives alone. All I wanted to know is if my mother was alright. I can't get to Napier, so I spun around and I backtrack all the way back to where I started from which is here, Omahu. I come all the way back to Fernhill and the road had being blocked off. Now I'm thinking, fuck, that was a dumb move what I did. Because my whānau, where's my whānau. I left my whānau at home here in Omahu. I wasn't thinking. But it happened so fast."

His family got out but their house was flooded. However, what hurt the most was something else.

"I lost my pride and joy. My Falcon. My Ford Falcon. When I finally caught up with my little brother a couple of days later he made me laugh actually. He said, 'What are you worried about your car for? You can replace your car. You can't replace your whānau.' I said, 'Brother, you're right'. I had to have a bit of a giggle to myself. Because he was right.

"I caught up with my mother about three or four days later when they opened up the bridge to Napier and she was a safe. The hard case thing about it when I get to my mother's house she goes, 'Oh don't worry about me son I'm alright'."

The lack of communications caused panic not just for the residents but for their families outside the area, said Watson.

"We've got a lot of my nieces and nephews in Australia and Sydney and they were hard out trying to communicate with me about my Mum and Dad. They were scared because they had heard they stayed in the house in the floods."

Joe Te Rito lives in Auckland but has family members living in the settlement in a house he owns. He knew that they'd stayed behind, but then had trouble getting through to find out if they were alright. He’d heard others had stayed behind and began to see images online of the water flooding through Omahu.

“There was just absolute madness. I was ringing up, texting and really worried and then we lost track because the power went off and we didn't know where our aunty was, didn't know where my cousin was because there was no contact. Then we're hearing that the Taradale Bridge was wiped out. I think in a way we as a community took the brunt of the flooding. Had that break in the bank not happened it could well have spilled over into Flaxmere and Hastings."

Many of those who left Omahu ended up evacuating to Flaxmere and Hastings, and were taken in by other marae communities such as Waipatu. Marae like Waipatu and Pukemokimoki that were not hit as hard became a base for not only people to stay but for distributing essentials like donated clothing and food.

Te Rito got down to Hawkes Bay within a couple of days and was immediately confronted with the reality of the damage and disruption to the burial grounds.

“One of the women came running up to me and gave me a fright actually. She says, 'What do I do with these?'. They were sort of yellowish bones. What we were told is the yellowish bones are the older ones.

"The bulldozers and graders had picked up and dumped the silt into a pile. Then somebody saw a bone and went and grabbed it and then realized there's quite a lot of bones in there. People were horrified. There were all these graves that were exposed and families were just totally freaking out about it."

Watson also had whānau who had found bones and were asking him what to do. There was no precedent, so community leaders had to improvise based on pragmatism and cultural principles.

“Whānau ran over to the truck I was in and said there's some bones here. So we had a look and there was a young girl that was doing nursing and she identified what kind of bones they were. The head stones were smashed over so the force of the water through here was quite strong. I called on my trustees and a couple of other key people and said, 'Hey, we need to do something and plan something'."

Leaders, including the church minister, gathered the community together and they walked around the roads and town in a line to try to recover as many of the remains as possible.

“We said to our people, 'Don't be afraid of them, because they're our own tīpuna and we're their tamariki mokopuna. And so we needn't and we shouldn't be afraid of them',” says Te Rito.

"We circled the perimeter conducting prayers, right around. All the traffic, they were respectful, they could see that we were obviously doing something like carrying out some sort of ritual.”

Tash Nuku works at Te Papa and drew on her contacts there for advice on repatriating the bones. Scientists were involved to test that there weren’t large voids in the cemetery and cranes and other machinery were used to reposition headstones and fill in holes with shingle. A pile of silt in the carpark will be sifted for any other bones.

The clean-up of the buildings and houses was a community effort as well and both Watson and Te Rito say the disaster brought together people from across the region.

“It's been difficult, but it's been a really good journey with our whānau and the volunteers that have come in to support the community, especially our non-Māori communities that live within hapū boundaries, like all our small farm owners, all the Pākehā that live here. On this first day of the actual clean-up I think we had over 600 people,” says Watson.

That kind of turn-out created an obligation to provide hospitality, which the marae did without missing a beat.

“We're providing lunch and dinner to whoever walks through our front doors. Big volunteer crews turn up for lunch or dinner. We provide breakfast for the ones that are staying here and we've had a lot of people come through our doors,” says Watson.

Te Rito says those who pitched in were a cross-section of the whole community.

“It wasn't just Māori by any means. There were a lot of Pākehā people with their shovels and tractors and diggers who'd come. In that first day or two they managed to strip all the houses of their carpets and all the wet furniture.They cleaned out all the houses.

“Our local Mongrel Mob guys were able to shine as well. I think we have a number of chapters of the Mongrel Mob in Omahu. And I don't know if they're in conflict with one another because I don't live here, but I know they are whānau. They have been impacted as well. They're human beings. It's affected their family. So they stepped up to the mark. I'm just really noting that they made their contribution. It was noted and well appreciated. They were pivotal in helping to carry the rubbish out onto the road."

Watson said that before Cyclone Gabrielle hit there were signs of old divisions starting to break down, with a community group forming in the area between the rivers.

“Between the Tutaekuri and the Ngaruroro River, the small farm holders, viticulture, horticulture, they wanted to come together as a catchment group. I saw that as an opportunity for us to move forward together because it's always been us and them. Some of the owners of the land still own the lands that were taken from our people by the Crown. They've been on those lands for over 150 years. They've always driven past here and just wondered, 'What happens over there in that community. What do they do, what do those Māori people do?' It was quite cool that we were able to join and start those conversations using the vehicle of between the two rivers. And this is a real partnership and the relationship is real. Let's move forward.”

The conversations started in that group are now focused on how the rivers have been managed over those 150 years and how things might look in the future.

“If you've been up in a helicopter to have a look, it's like the rivers have tried to take their natural courses back, especially the Tutaekuri. You could just see they've diverted the river to one side of the valley, but it's taken the whole valley back when that water came down. Its natural course was the whole valley, but for an economic cause they choked it up.”

There’s also a number of difficult decisions around how to rebuild and where. Te Rito says some of the houses are so damaged they should be condemned but insurance companies and assessors are deciding to repair houses that have been filled with silt and raw sewage. The bureaucracy and decision-making sounds eerily similar to what people in Christchurch faced for years after the earthquakes.

“I’ve had sewage around my house. Inside under the floor. I've got a concrete rim foundation, so it's sitting in there and it stinks. Our insurer came, and I was kind of saying to him, I wouldn't have minded a red sticker and then I can rebuild.

“But in my case, I've been told that the floors can be removed and then we'll remove the sludge. But, at the moment, I don't want my cousins living there, one of my two cousins has had cancer, and she can't live in the house.

“I'm just worried because of the health risk. That pollution is in our floorboards, it's in the sides of the house.”

There are conversations happening about whether the whole community should relocate to higher ground rather than rebuild in the same location only to get flooded again. While some have insurance, others don't.

If there are many in the Omahu community vulnerable in the wake of the cyclone, many were already vulnerable before it hit. A number of the residents are elderly and looking after mokopuna, while others are hesitant to seek help because of negative experiences with government agencies in the past.

“We've had MSD here supporting the community for the last week and a half. But we're still having to pull whānau out of the home and say it's okay to come in. Share a couple of details and you'll get this. Share your name, date of birth, bank account, tell them what you're going through and we'll get the support,” says Watson

“But we're having to go draw those families out because they've been let down so many times or they're not allowed back into those buildings because once they get upset, you know, things happen, they get trespassed and things like that. But it's one of the reasons we requested people to come here because it's a safe place for our people. We've been able to draw those ones out to seek support.”

Watson is less than complimentary about some of the local bureaucracy.

“I got a phone call from council and the lady on the other end said, ‘Hey, we're putting a plan together. We'll get a couple of skip bins out to you guys on Sunday and we'll pick them up on Tuesday.’ I just said, ‘Are you for real?’”

The rubbish that had been cleared out of houses by that stage had nearly filled up an entire paddock and there was more.

“They're creating all these plans, all these actions without even seeing what was here in the community and how we are operating. Civil Defence have been really no help to us. A lot of promises have been empty.

“We know there are these big funds out there – the mayoral fund, the funds that have been released by Government in regards to supporting communities in need. We hope we're not overlooked because it seems that we can cope by ourselves, because at the end of the day those resources come from our personal pockets. So we hope we're not overlooked and it goes to places like Havelock North.”

But Watson again circles back to the locals' resilience.

“I’ve been really proud just seeing the community stand up together to do what's needed.”