When Super Bowl LVI kicks off at SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, Calif., it will symbolize a homecoming of sorts. After all, 55 years ago the very first Super Bowl played out in the balmy shadow of the HOLLYWOOD sign as well. A lot has changed since then—both in terms of football’s ascent as the national pastime and the size and scale of big-studio blockbusters—but the NFL and movie industry have, in many ways, matured into hand-over-fist success stories, side by side. In fact, you could say that the first Big Game between the AFL and NFL champions at the Los Angeles Coliseum was its splashy Tinseltown premiere.

Illustration by The Sporting Press; Getty Images (Any Given Sunday); Everett Collection (Two-Minute Warning); LMPC/Getty Images (Black Sunday blimp); Warner Bros./Everett Collection (Goonies, The Blind Side); Warner Bros./Getty Images (Hooper, Police Academy 2); Mary Evans/Ronald Grant/Everett Collection (Heaven Can Wait); Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images (Black Sunday); Kirby Lee/USA Today Sports (SoFi sign); Bettmann/Getty Images (Namath); Ben Oldender/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images (jet pack)

Today, the NFL’s marquee event reaches 150 million viewers around the world. Meanwhile, Hollywood is responsible for one of the U.S.’s leading exports: pop culture. And the synergy between football and the film industry has never been stronger. The Super Bowl gooses its ratings each year with its starry, shock-and-awe halftime shows, while the movie industry shells out $5.5 million for each 30-second ad during the Big Game to give sneak peeks at its latest shoot-the-works franchise wares. Sometimes it seems as if one uniquely American form of escapist entertainment is eating its own tail—at a corner booth at the Ivy, naturally.

This symbiosis only seems to be getting stronger: Just recall Brad Pitt’s stentorian introduction before last year’s Super Bowl, hailing the generational matchup between Tom Brady and Patrick Mahomes. So as the Big Game returns to La La Land, we look back at some of the most memorable moments in this long—and sometimes awkward—relationship.

On Jan. 15, 1967, Vince Lombardi’s dynastic Packers routed the AFL’s scrappy Chiefs 35–10 in Super Bowl I. But the showdown that would usher in a new era for the sport was seemingly slapped together with Scotch tape and chewing gum. The site for the game wasn’t even chosen until a mere six weeks before kickoff. Still, the one aspect of the inaugural game that was not left to chance was the halftime show.

NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle bristled at calling the game “the Super Bowl,” which he thought was too gimmicky and glib for what he perceived to be the lofty stature of his league. (He preferred “the Big One.”) In the end, organizers went with the more straightforward (and decidedly uncatchy) “AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” the “Super Bowl” moniker not becoming official until two years later.

As the event approached, it was clear that it was not going to be a sellout: Approximately 32,000 of the 93,607 seats at the L.A. Coliseum were empty. But Rozelle was smart enough to know that his new championship would live or die by how it came across to the 51 million fans watching on TV. To prevent those viewers from turning the channel at halftime, organizers decided to turn to someone who understood the priceless value of razzle-dazzle. Luckily, they were already in Hollywood’s backyard.

Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Tommy Walker had been a bigger-than-life promoter on Walt Disney’s payroll since the opening of Disneyland 11 years earlier. Like P.T. Barnum, albeit in a crisp cardigan and with a head full of Brylcreem, Walker dreamed big and could conjure special events like a magician. Turning the mundane into the memorable was his life’s work: He was the man who came up with the six-note “Charge!” fanfare, after all. He was tasked to deliver some Hollywood pomp and pageantry during halftime, and he did. Most famously, with a pair of daredevil jet-pack pilots from Bell Aerosystems who zipped around the Coliseum 60 feet above the field just like James Bond had in Thunderball. It was the Super Bowl’s first Tinseltown moment, and it wouldn’t be the last. The Coliseum and the Rose Bowl in Pasadena would end up hosting the Big Game another five times combined, each time tapping into some of Hollywood’s glamour.

On the film front, the 1970s brought a string of big-budget, star-studded disaster movies. These pandemonium-drenched epics were more than just another cinematic fad; the studios were responding to something in the zeitgeist. Airport (’70), The Poseidon Adventure (’72), The Towering Inferno and Earthquake (both ’74)—the list goes on. At the back end of this tsunami came two films that would occupy a very specific subgenre: the Super Bowl Disaster Movie.

As news about hijackings, corrupt institutions, an unwinnable war, and disasters both natural and unnatural dominated the headlines, moviegoers chose to exorcise their fears at the multiplex. It was entertainment as mass catharsis. In 1972 grand-scale dread had even touched the usually peaceful world of sports when eight members of the Palestinian terror group Black September stormed the Olympic Village at the Munich Games and murdered 11 Israeli athletes. Taking a page from the world of fact, Hollywood would release a pair of Super Bowl disaster flicks just a year apart.

First out of the gate was 1976’s Two-Minute Warning, a not-so-white-knuckle thriller based on a bestseller by George La Fountaine about an unhinged sniper picking off fans at the Super Bowl. Since the filmmakers—shockingly—couldn’t get the NFL’s cooperation, the Super Bowl is called “Championship X” in the film, a matchup ostensibly between Baltimore and Los Angeles, with no team nicknames mentioned or logos shown. The actual squads shown on the Coliseum field are USC and Stanford—B-roll footage taken from a ’75 Pac-8 game.

Although Universal spared no expense when it came to casting—disaster-movie staple Charlton Heston is the topliner, joined by a veritable Love Boat of supporting players, including Jack Klugman, John Cassavetes, Beau Bridges, Martin Balsam, Gena Rowlands, David Janssen and Walter Pidgeon—the film is a by-the-numbers, Whitman’s Sampler of mini-melodramas that collide at the Big Game when hell breaks loose. The sniper’s motivation is never clear, not enough attention is placed on the game and the film’s idea of an A-list football cameo is retired NFL quarterback Joe Kapp, who looks as if he’s on the shady side of 50. We never even find out who was winning the game before its 90,000 fans scramble onto the field screaming their heads off while ducking bullets.

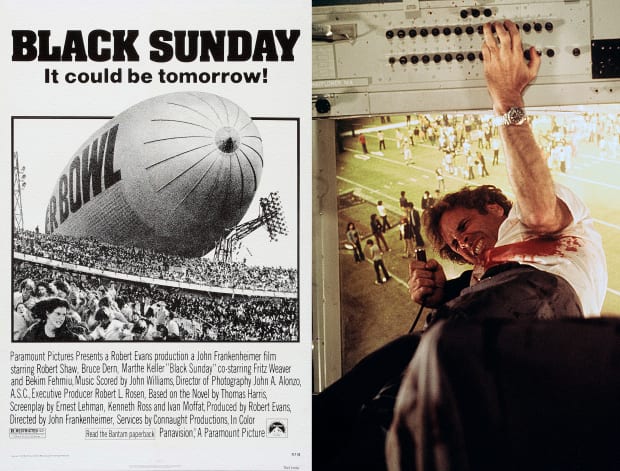

Far better is 1977’s Black Sunday, which feels as suspenseful as a game clock during a tight fourth quarter. Based on a novel by Thomas Harris (who would go on to write The Silence of the Lambs), this slice of red-meat action follows a former POW (Bruce Dern) who, after being manipulated by a terrorist operative, pilots the Goodyear blimp (yes, Goodyear agreed to this product placement) into Miami’s Orange Bowl, intent on detonating a shower of lethal darts into the crowd. Thanks to solid performances from Dern as well as Marthe Keller (as his German terrorist handler) and Robert Shaw (as a Mossad agent), Black Sunday is actually one of the better entries in the ’70s disaster cycle. It’s a sweaty procedural with excellent taste when it comes to product placement—the thing that tips Shaw off to the terrorists’ target is a copy of Sports Illustrated.

LMPC/Getty Images (poster); Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images (Dern)

For football lovers it also doesn’t hurt that the championship game looks and feels real ... because it is. Producer Robert Evans sweet-talked the NFL and Dolphins owner Joe Robbie into giving the project their blessing. As a result, legendarily crusty director John Frankenheimer and his crew were able to shoot footage from the Orange Bowl’s sidelines during Super Bowl X, between the Steelers and the Cowboys. During one tense sequence, as Dern and his would-be deadly blimp nosedive into the roaring stadium, we get a nice, extended glimpse of Terry Bradshaw throwing a touchdown to Lynn Swann. And if you’re deft with the pause button, you can also spy Franco Harris, Roger Staubach and the dapper coaches, Tom Landry and Chuck Noll. Dern is riddled with bullets before he can execute his deadly plan, and the movie version of game spirals into chaos, but at least anyone can look up the actual outcome: Steelers 21, Cowboys 17.

Hollywood’s fascination with the Super Bowl hasn’t just been limited to fictional snipers and killer blimps. The game has served as both a setting and plot point in a handful of non-disaster movies over the years. Which isn’t to say that the movies weren’t disasters in their own right. In 1980’s Where the Buffalo Roam, Bill Murray dons aviator sunglasses and ingests several vials of illicit substances as gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Several episodes from Thompson’s lysergic reporting career are sandwiched together in the film, but the most interesting one chronicles Thompson’s trip to cover Super Bowl VI. Of course, he never sets foot inside the stadium to witness Staubach’s MVP performance in the Cowboys’ 24–3 rout of the Dolphins. Instead he’s persuaded by his equally unhinged lawyer (Peter Boyle) to join a band of freedom fighters to smuggle weapons to Latin America.

A more recent movie only slightly more concerned with what happens on the gridiron is the 2015 con-man caper comedy Focus. Will Smith and Margot Robbie (no relation to Joe) share whatever the opposite of chemistry is as a couple of grifters who crisscross the globe trying to separate obnoxiously rich suckers from their money. Focus desperately wants to be a contemporary, his-and-hers version of The Sting, but it just sort of sits there, unable to spark to life. (It needed either a different pair of stars or a defibrillator.) Still, one scene that does work involves an intricate swindle at Super Bowl XVII, pitting the “Rhinos” against the “Thrashers.” Since it’s become harder and harder to get the litigiously overprotective NFL to sign off on using the league’s actual teams and uniforms in movies (see the ridiculous jerseys and color combinations in Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday), the players on the field look like they’re a part of some XFL smackdown, or worse yet, Transformers: Age of Extinction. Still, the con is a honey, as Smith bets a deep-pocketed gambler (B.D. Wong) $2 million that he can tell him the uniform number of the player he’s thinking of. Naturally, he guesses right.

More up-to-the-minute is American Underdog (2021), an inspirational story based on the unlikely career arc of Kurt Warner. The film traces all of the stations of the cross in Warner’s rise from supermarket checkout clerk to starting quarterback of the St. Louis Rams to the MVP of Super Bowl XXXIV. But despite Warner’s helming the Greatest Show on Turf to a 23–16 win over the Titans that was decided on the last play, the action sequences from the game are perfunctory, proving that while Hollywood knows how to tell a story about characters—Shazam’s Zachary Levi does Warner justice in the starring role—it tends to whiff on Super Bowl reenactments.

Finally, and sticking with the Rams (although this time during their original tenure in L.A.), there’s the most famous—and most decorated—Hollywood movie to orbit around the Super Bowl: Warren Beatty’s 1978 Best Picture nominee, Heaven Can Wait. A loose update of 1941’s Here Comes Mr. Jordan, Beatty stars as Joe Pendleton—a QB for the blue-and-yellow who’s prematurely taken to heaven by an overzealous angel (Buck Henry). Realizing his error, the angel places Pendleton in the body of a millionaire industrialist who has just been murdered by his wife. In his new corporeal form, Joe, still hungry for a Super Bowl win, decides to buy the Rams and lead them to a championship—which he accomplishes, of course, in the climactic third act, with a victory over the Steelers. Not everyone would call Heaven Can Wait a Super Bowl movie, or really even a football movie. But it would turn out to be eerily prescient: The Rams actually did meet the Steelers in Super Bowl XIV, less than two years after the film’s release. There was no divine intervention for the Hollywood team, though, as Pittsburgh cruised to a 31–19 win.

The pipeline between a successful professional football career and a second act on the silver screen was once as improbable as going from supermarket check-out clerk to Super Bowl MVP. But the klieg lights that shine on the most-watched annual sporting event in America occasionally have the power to transform even lunch-pail players into postretirement movie stars. While some of the biggest names to swap their NFL unis for SAG cards belong to players who never made it to the Big Game (see: Jim Brown, Alex Karras, O.J. Simpson, Bernie Casey, Carl Weathers, Brian Bosworth, Terry Crews, et al.), there’s no denying the extra volt of celebrity wattage that comes with competing on the sport’s biggest stage.

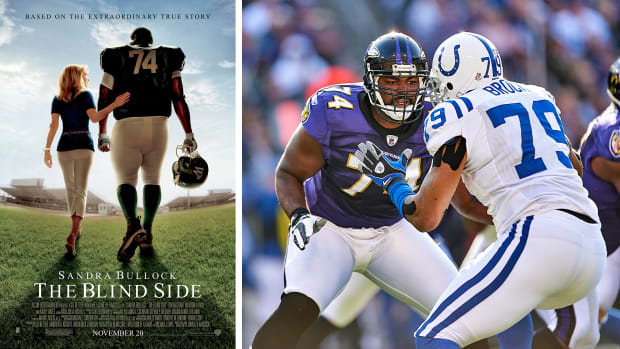

Occasionally, however, it’s the movie character who makes his way to Super Sunday, as was the case with offensive tackle Michael Oher, whose reputation preceded him in the NFL thanks to his pivotal role in Michael Lewis’s 2006 bestseller, The Blind Side—and the eventual movie adaptation that won Sandra Bullock an Oscar in ’10. A first-round pick of the Ravens in ’09, Oher arrived in the NFL with the sort of origin story that only Hollywood could dream up. While he ultimately failed to deliver on the promise of superstardom, he did snag a ring after the Ravens’ 34–31 Super Bowl XLVII victory over the 49ers.

Warner Bros./Everett Collection (poster); Al Tielemans/Sports Illustrated (Oher)

Oher is an exception, a fluke. Nine times out of 10, the path runs in the opposite direction: NFL first and Tinseltown second. (And by Tinseltown, we’re talking about an echelon higher than moonlighting as a TV pitchman flexing the “Discount Double Check.”) In fact, you don’t have to look any further than a veteran of the very first Super Bowl to find a particularly badass example. Known for the brutal forearm shivers he delivered to opposing wide receivers, defensive back Fred “The Hammer” Williamson played eight stellar seasons in the pros—the last helping the Chiefs reach the AFL-NFL World Championship Game. His team lost, but by that time Williamson had become one of the most feared players in the game. Naturally, Hollywood came calling. Williamson found quick work in the 1970s Blaxploitation boom, starring in Black Caesar, Hell Up in Harlem and Three the Hard Way. Sensing a natural, Hollywood soon put him in more mainstream roles. At 83, he’s still working and has stacked up more than 100 acting credits.

Oscar nominations and other accolades have never been the point. The mere fact that an NFL player could transition from winning Super Bowl V to starring in Police Academy 5, as defensive end Bubba Smith did is, in itself, remarkable. Hollywood might not have gotten the better end of the deal when it cast Terry Bradshaw alongside former Florida State star running back Burt Reynolds in Hooper or The Cannonball Run, but one thing is certain: The Goonies wouldn’t have been half as memorable as it was without two-time Super Bowl champ John Matuszak going berserk for a Baby Ruth as Sloth.

Joe Namath was already “Broadway Joe” by the time he predicted a win for the Jets in Super Bowl III. So it made perfect sense that the tabloid playboy would parlay his on-field fame into a movie career. But he never seemed as comfortable on the big screen as he did at midfield being interviewed after a game-winning drive. After hosting a 1969 variety show, movie offers came and he took them, but Hollywood studios learned the hard way that just because your nickname has “Broadway” in it doesn’t mean you can act. As Exhibit A, check out the 1970 biker movie C.C. and Company. Or, better yet, don’t.