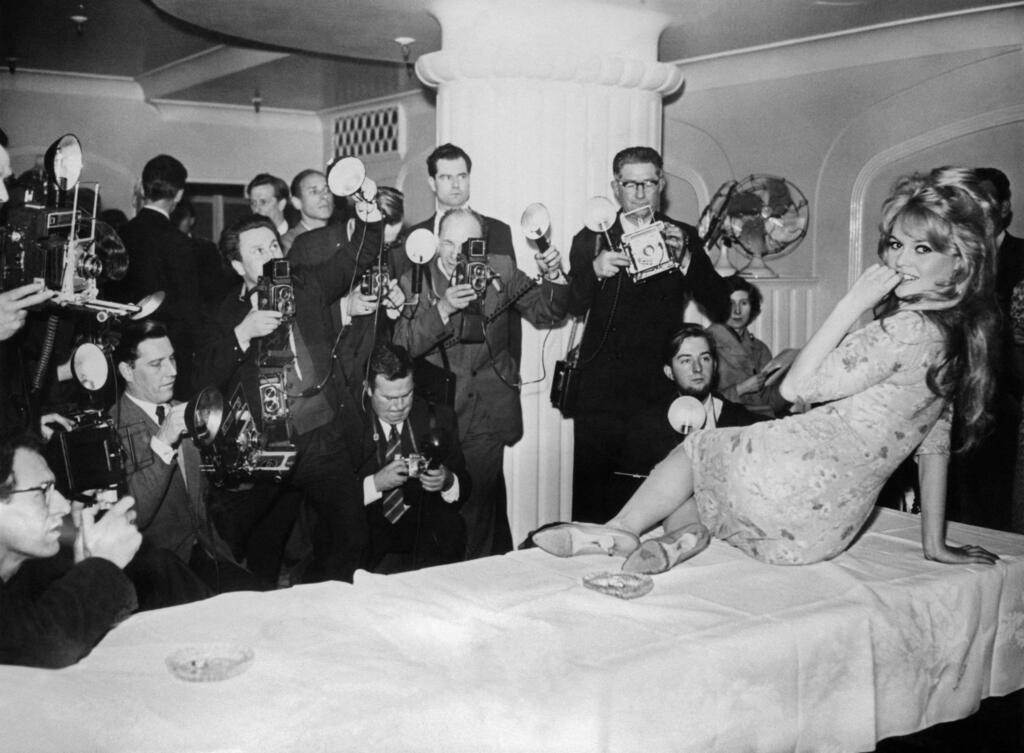

Brigitte Bardot, who died at the age of 91 on Sunday, lived a life filled with contradiction and controversy, but became a global icon first and foremost through film. RFI spoke to critic and historian Antoine de Baecque about her legacy in cinema and beyond.

RFI: Bardot was very young when she started her film career. It was ultimately quite short but very intense, and left its mark. In what way do you think she embodied an era?

Antoine de Baecque: Brigitte Bardot represents a little piece of France that is disappearing. She embodied several moments in cinema, several eras – between her appearance in the late 1950s, which coincided with the emergence of a new style of cinema, the New Wave, and then on to films that were huge successes, both in the United States and in France. Then she said goodbye to it all very young – she ended her film career at the age of 40, in the early 1970s.

Bardot was always a kind of reflection, a mirror... that reflected the developments of the moment. And that's what's so powerful about Bardot in cinema, it's that way she has of signifying something – like a phenomenon, like an apparition.

Remembering Bardot: ‘sex symbol', ‘crazy cat lady’ and far-right supporter

RFI: Her appearance in Roger Vadim's And God Created Woman in 1956 caused a sensation in the film industry and she was elevated to the status of a symbol, a sex symbol.

ADB: It's a paradoxical story, that God created Roger Vadim's woman, because for Vadim [this film] was first and foremost his way of creating a woman: here is the Nouvelle Vague girl. This young woman who is going to be a bit of a model for her era.

And it wasn't necessarily very well received. And God Created Woman was not a huge success when it was first released in France. In fact, it was when it reached the United States that the Bardot phenomenon took off in 1958.

RFI: Two years later...

ADB: Exactly, the film is French and is received [in France] with very mixed reviews. It is considered very shocking for its nude scenes, for its very transgressive nature compared to the young leading ladies of French cinema in the 1950s, which was still a fairly restrictive, very moralistic cinema.

And then the film is released in the US where it became a real phenomenon, in the sense that American youth elected Bardot as the sex symbol of her time.

RFI: The British press said Bardot in the film was the biggest shock since the French Revolution in 1789. It immediately took on a global dimension, it wasn't just France.

ADB: Of course, [this shock] was seen in the US and the UK and even Italy. And it was this international [reaction] that, in a sort of boomerang effect, came back [to France] and on its second French release, it was a huge success.

Bardot... was truly a new [type of woman] in cinema, with this very frank, very free way of showing her body, this completely new way of choosing her men, compared to the customs of the time. She was no longer the prey, she was the predator, in a way. And that was something completely new.

Bardot: the screen goddess who gave it all up

RFI: She became an international megastar. And yet it wasn't until 1963 that she starred in a true masterpiece, Le Mépris (Contempt).

ADB: Bardot can only be herself. That's her greatness – she can only play herself, she can only speak in her own way, she can only appear in her own way. And so she will always struggle with cinema which wants to give her characters to play.

In Le Mépris, Jean-Luc Godard really uses her as a plant, as he says – she is a beautiful plant and there is something almost objective about it. Particularly, of course, in the famous scene that opens the film, which was actually shot later on, when Godard, in response to his producers who wanted Bardot, said: "Well, here you go, I'll give you Bardot." So we get a nude scene that would become a legendary scene in world cinema.

RFI: Was she a great actress, in your opinion?

ADB: No, I don't think she was an actress. She didn't really like cinema herself. You know, she was there, but she didn't consider herself an actress. What she liked was being with her friends, partying or relaxing at home, in her refuges at La Madrague, [her beach house] in Saint-Tropez or [her home in] Bazoches [near Paris].

But Bardot knew very well that cinema was necessary. It was the means to become famous, the means to conquer the world. And she did it. But not as an actress. She wasn't an actress, she was a phenomenon.

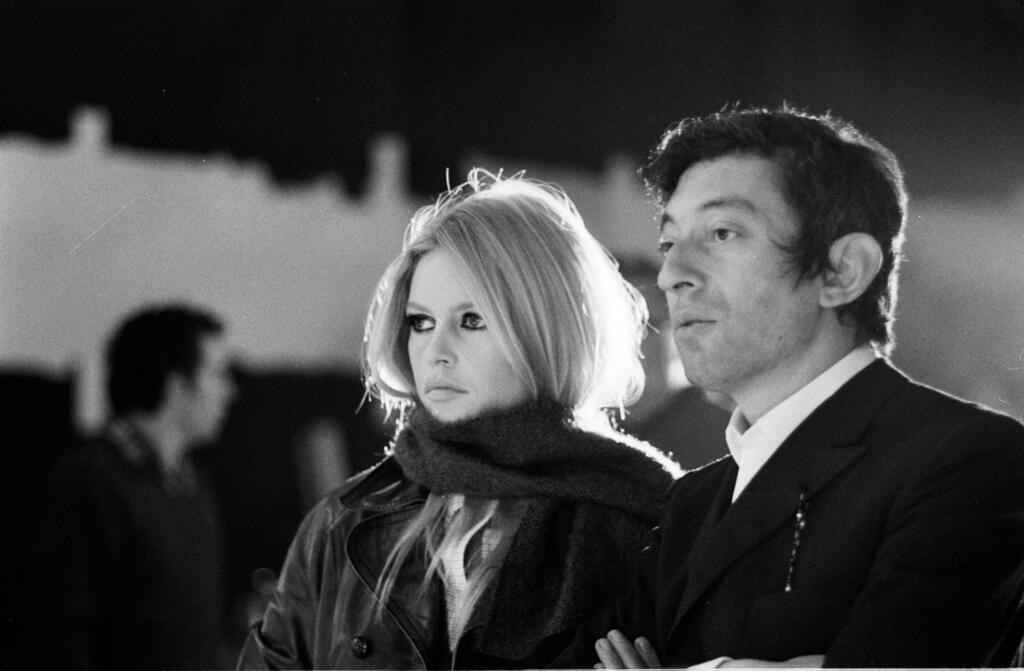

She loved to sing. She had passions. She always loved animals. That was an instinctive [thing] she always had – that is, taking in animals and defending them, and attacking very vehemently those who mistreated animals. And singing was something she did a lot, with people who wrote songs for her. La Madrague is a song that was written for her in the early 1960s. And then, of course, there was the meeting with Serge Gainsbourg...

First and foremost, it's a love story. A passionate story of three months of mad love in the autumn of 1967, which resulted in these masterpieces of French chanson: Harley Davidson, Comic Strip, Bonnie and Clyde. And then, of course, Je t'aime... moi non plus, the legendary song recorded on 10 December 1967 – which was about Bardot at a time when she was involved in a love affair [with Gainsbourg]. [The record was shelved because Bardot didn't want her husband at the time, Gunter Sachs, to find out.] It [was then] covered by Jane Birkin [Gainsbourg's subsequent love interest] before we even got to hear Bardot's version.

Jane Birkin, an English chanteuse who left her mark on French pop

RFI: Bardot said that Initials BB, a song Gainsbourg wrote about her, was the most beautiful declaration of love she ever received.

ADB: Yes, that's absolutely right. I think that between Bardot and Gainsbourg, it's both mythology and at the same time something that they shared intimately. No one can ever take that away from them. It's truly a love story that became songs.

And that's something that is also Bardot's strength: that she chooses. At one point, she wanted to choose Gainsbourg because she loved the way he looked at her, the way he desired her, and she chose Gainsbourg over everyone else, over everything – her husband, convention, social norms, what people might say.

And the song Je t'aime... moi non plus is the embodiment of this passion. Bardot may have had a passion for certain men but, in a way, passion itself her true love – this way of loving that was very shocking for the times she lived in, being free to love and then to throw that love away. I think that's the very essence of Bardot, that choice.

This article has been adapted from an interview in French by RFI's Charlotte Idrac and edited for clarity.