When Walk the Line strode into cinemas in 2005, all dressed in black, it gave final shape to a template that Hollywood has been copying ever since. James Mangold’s Oscar-winning Johnny Cash film – following on the heels of Ray, Taylor Hackford’s similarly awards-garlanded take on Ray Charles a year earlier – established the music biopic blueprint so definitively that the form immediately ossified into cliché. Troubled childhood, early brilliance, meteoric ascent, drugs and adversity, redemptive finale. By the time Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story came along to skewer the whole charade in 2007, the parody practically wrote itself.

Fast-forward 20 years, past the vapidly formulaic Bohemian Rhapsody, and we’re still being served the same meal with different garnishes. A Complete Unknown and Springsteen: Deliver Me from Nowhere – biopics of Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen respectively – both arrived a year apart; Sam Mendes’s Beatles quartet is slated for 2028. We’re at saturation point. So the news about Cameron Crowe’s Joni Mitchell biopic ought to inspire a chorus of groans. Except for one thing: they’ve only managed to rope in “21-time Oscar nominee and three-time winner” Meryl Streep!

In 2004, paying tribute to Streep, Nora Ephron – whom the actor had essentially portrayed in the from-life marriage-breakdown drama Heartburn – observed that she “plays all of us better than we play ourselves”. Streep has received two Oscar nods for playing musicians – the violinist Roberta Guaspari in Music of the Heart, and the tone-deaf socialite in Florence Foster Jenkins. Her ability to inhabit artists who operated outside convention feels peculiarly suited to Mitchell. What could Streep capture that matters?

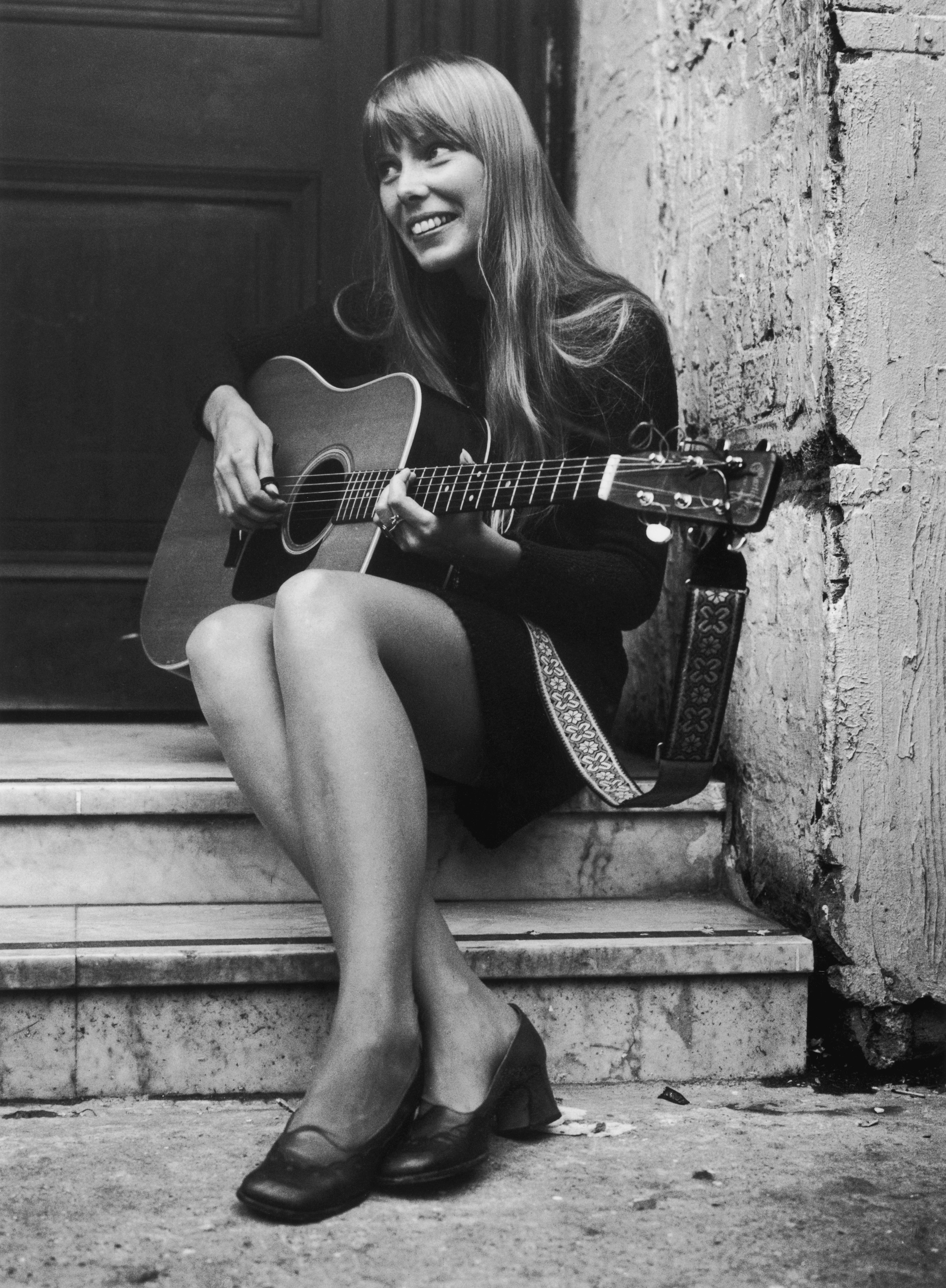

The cerebral quality, for one. Mitchell has never just been instinctive; she is intellectually rigorous about her craft, analytical about the architecture of a song. The absence of sentimentality, too – even in her most vulnerable work, there’s a clear-eyed refusal to wallow in self-pity.

Mitchell could be prickly, exacting, uninterested in performing traditional femininity or playing the ingenue. She made uncompromising art, on her own terms. Streep understands women who refuse to be easily categorised, who insist on complexity. And what’s more, she has the technical chops to make Mitchell’s aching vocals seem effortless. Whether it’s the tremulous patriotism of “God Bless America” in The Deer Hunter or the country-western heartbreak of “You Don’t Know Me” in Postcards from the Edge, Streep knows how to use a song to crack someone open.

Then there’s Crowe, whose brilliant, bittersweet Almost Famous is a tie-dyed hymn to the wild-eyed rock scene that exploded between Sixties idealism and punk nihilism. His Oscar-winning screenplay captured not just the touring and the glamour but the moment the music industry got hijacked by marketing men. Having started writing for Rolling Stone aged 15, Crowe was immersed in that milieu when Mitchell was at her imperial peak. He understands not just the mythology of that era, but the specific pressures and possibilities of being an artist in the Seventies. More to the point, he’s spent four years in regular meetings with Mitchell, working from her own account of her life rather than some authorised biography. “It’s through her prism,” he has said. Such intimacy matters.

The film will apparently employ a dual timeline structure, with Anya Taylor-Joy rumoured to play the younger Mitchell. If true, it would allow the narrative to move between the Laurel Canyon years – all that sun-dappled bohemianism and the love story with Graham Nash that gave us Mitchell’s “Willy” and Nash’s “Our House” – and Mitchell’s later reinventions, her survivals, her refusals to become a heritage act. Not just the greatest hits, then, but the full arc.

And yet. Just as Hollywood became fixated on remakes and comic-book franchises in the last decade, so it now seems equally besotted with the musical hagiography. Is it symptomatic of an industry that’s run out of original ideas? Or just a case of tapping into our fascination with the stars of a bygone musical era? Either way, the track record isn’t encouraging. Springsteen: Deliver Me From Nowhere, by and large, earned positive reviews, but underperformed at the box office, grossing around $45m (£36m) worldwide against a $55m (£44m) budget. Not helping, either, is the fact that music biopics now face the same “they don’t look right” pile-on before a single frame is shot. The photos of the actors made up as John, Paul, George and Ringo in Mendes’s production inspired immediate uproar this week. A Complete Unknown, meanwhile, opted for myth-making over fact – especially in its closing emotional resolution. These films seem almost guaranteed to underwhelm.

Which is why Mitchell’s direct involvement feels important. She famously squelched a proposed biopic that would have starred Taylor Swift years ago, later remarking with characteristic brusqueness that she’d never heard Swift’s music. She’s protective of her story, and choosy about who gets to tell it. If she has blessed this version – with Crowe’s deep understanding of the period and Streep’s knack for transformation – then it says more than the usual approved-by-the-estate imprimatur. The genre’s trajectory demands caution. But this casting suggests someone’s grasped that you could drink a case of Joni Mitchell and still not reach the bottom.