PwC administrator asks Govt and other creditors to keep ski fields operator afloat over summer until a new company can be set up – or face a bill of nearly $150 million to clear the debts and restore the mountain

When the last few skiers grated to a halt on the gravel at the bottom of Whakapapa ski field this week, one question was on everyone's mind: will Ruapehu Alpine Lifts ever open to skiers and snowboarders again?

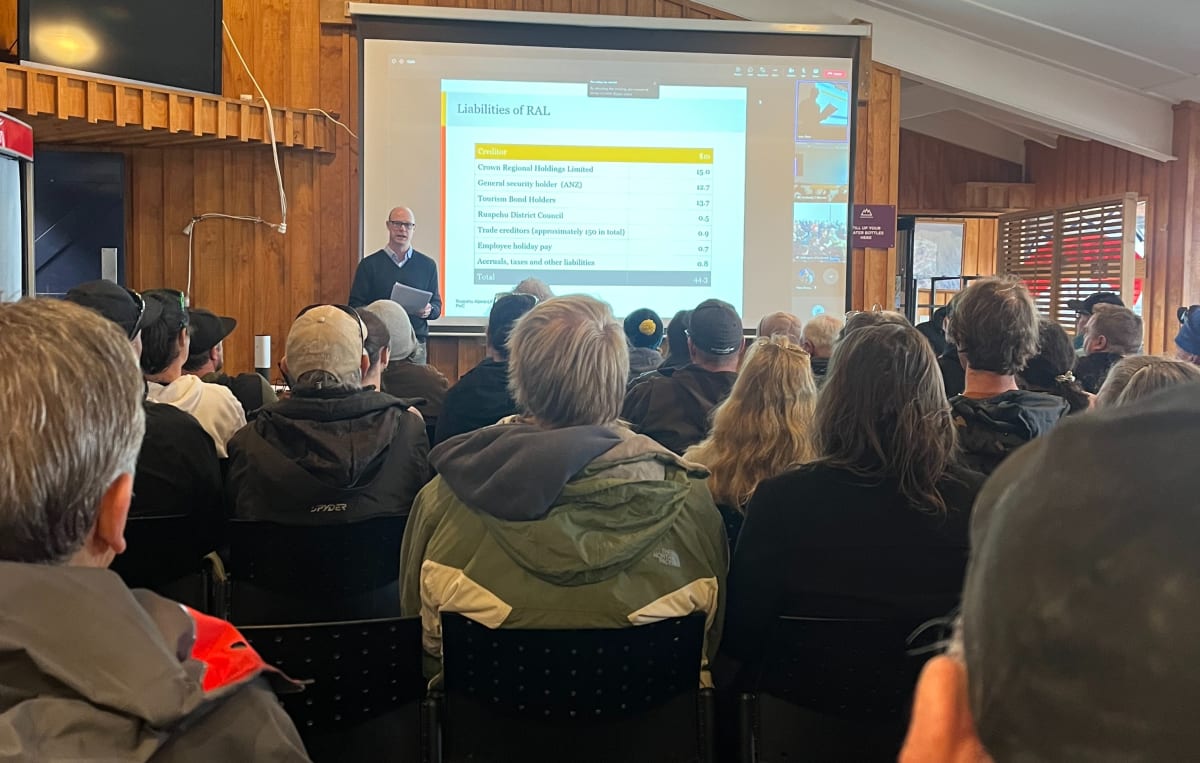

John Fisk, the voluntary administrator appointed last week by a meeting of 400 life pass holders and other creditors, is cautious. He tells Newsroom he's confident that with the support of bondholders such as MBIE, ANZ and Ngāti Tuwharetoa, he can find a workable solution to reopen the slopes – but not under the management of the discredited not-for-profit company that has operated them for the past 70 years. "There's over $44 million of debt there, so the prospect of that happening is probably reasonably low."

Newsroom has spoken with the company's past leaders and creditors about what went wrong, and how best the weathered remains can be salvaged. Those investigations reveal plans to bring in some of those past leaders like Dave Mazey to negotiate a solution – because the alternative, Fisk says, is too costly to contemplate. "If the Department of Conservation licence is cancelled, there is an obligation on Ruapehu Alpine Lifts to remove all the infrastructure that's been put in place, to leave the mountain, essentially, pristine."

JP Chevalier ran Turoa for two years, until he left in November 2019. The lifelong skier still has a photo, shown above, of his last sunset run in a favourite spot on Koro Ruapehu. He has never skied since, he says.

He spoke to Newsroom from South Australia, where he now works in the horse breeding industry. After a career on ski slopes around the world, he's relishing the change.

After arriving at Ruapehu Alpine Lifts in 2017, he had assessed the company's opportunities to succeed financially and deliver on customers' expectations. Three months into the job, he recommended to the new chief executive, Ross Copland, that the business simplify its product offering, staff resources, operations, guest services and infrastructure. For a customer to ski the mountain, they had to choose from hundreds of ticketing and pass options.

This much, everyone agrees: most of the world's big commercial ski fields earn a buck pretty much every day of the year. But on the windswept slopes of the volcano Ruapehu, the ski fields company had just 90 to 120 potential operating days a year, and as few as three to eight days were truly profitable, based on regression analysis.

Chevalier's call to urgently focus on simplifying the business wasn't adopted, he says. It soon became apparent to those inside and outside the company that he and the chief executive were at loggerheads. Chevalier took sick leave, then left. It was a "dark time" in his career.

The company published 10-year projections for winter and summer visitor growth, assuming it would open gondolas on Whakapapa and Turoa. But it was all a pipe dream.

“I am sad for the life pass holders, local iwi and the general community who seem to be betrayed and left with devastation," Chevalier says.

But blaming Covid-19 or this year's lack of snow would be to miss the point, he says.

He believes Ruapehu Alpine Lifts does have a viable future, but it needs new leadership that links shareholders, iwi and more. "My answer is yes, provided there’s a recruitment of fresh minds that hold broad industry expertise, experience and capability to break conventional mountain playground business modelling," he says.

"Mt Ruapehu is a unique and special place requiring ultra creative social and emotional connectivity to ignite its existing and potentially new target audiences.”

He will likely get his wish. With Fisk signalling a new operating company will be needed, there is unlikely to be a place for long-serving chair Murray Gribben or the more recently appointed chief executive Jono Deans.

Dave Mazey, a well-liked local who ran Ruapehu Alpine Lifts for 30 years up to 2016, is set to return to work with the voluntary administrators on liaison with iwi and the community – though he has no interest in returning to operational management.

"We see someone like Dave Mazey as being a really important part of the process, because he has relationships, he understands what's happened there," Fisk says. "There will be some people that don't agree with what he's done in the past, but he also has a depth of knowledge that I think will be really valuable to us."

Mazey, 70, still lives just up the highway in Taupō. "Without sounding arrogant, or overly confident, I have a deep understanding of the place," he says.

Mazey grew up at Whakapapa Village, worked as a park ranger in the early 1980s, and then at the government department that managed Tongariro National Park, before moving across to the leadership of Ruapehu Alpine Lifts.

Back then the company operated Whakapapa, but in 2000 it purchased the near bankrupt Turoa off its receiver – a certain John Fisk. The two men have worked together before, and trust each other.

"The long-term aspiration that I would have is that we get an outcome here that actually meets and enthuses all of the stakeholder groups," Mazey says. "There are the life pass holders who have made what, for a lot of them, was a big financial commitment. There's the aspirations of the communities, especially Ruapehu and Taupō districts.

"And most important, can we meet the aspirations and expectations of the iwi? The maunga, he's koro, their grandfather. He's just important to them.

"There's a lot of them who will look at me and say, this is koro speaking, he actually doesn't want you to be up there at all. And I can understand that. I've heard those stories, listened to those stories, and developed at least a Pākehā understanding of them. I think there's a way that the aspirations of iwi, expressed over 30 years, can be better met.

"It's very hard for many to accept that there's a business run up there on their mountain, that creates wounds in the body of koro with its ski lifts, that causes him to weep at times because he hurts, that doesn't allow him to sleep because there's there's light shining all over the place at all hours."

What are the options?

Janelle Hinch, 39, first skied on the slopes of Ruapehu as a six-year-old, holidaying with her Auckland family. She fell in love with the maunga and, as soon as she left school, she moved to Ohakune to make a new life on the central plateau.

Hinch now has her own Opus Fresh outdoor fashion label that she sells online, and from her Ohakune store, and from the retail outlets at Ruapehu Alpine Lifts. That makes her an on-again-off-again trade creditor, as well as being a life pass holder and a Ruapehu district councillor.

She wasn't able to make it up to the creditors' meeting – like many small business operators, she had to run her shop when a staff member called in sick. But she supports a proposal, put forward by life pass holders, to crowd source more funding to operate the ski fields.

There are some like Mazey who would argue that Ruapehu Alpine Lifts was the original example of crowd-sourcing, when ski clubs and skiers set it up in 1953. They all contributed to the cost of New Zealand's first chairlift, a single seater diesel-electric driven lift capable of taking 350 people an hour up to Hut Flat.

That's assuming the administrators can't achieve the default solution: to restore Ruapehu Alpine Lifts Ltd to profitability with the assistance of more finance from existing bondholders such as Crown Regional Holdings (already owed $15m), ANZ Bank ($12.7m), and tourism bond holders such as Ngāti Tuwharetoa and Taupō District Council ($13.7m).

Assuming that can't happen, Fisk suggests iwi partnering to establish a Newco. What that structure might look like is not yet clear – but it's the administrators' most likely option at this stage. That might involve the Government agreeing to write off some or all of the $15m it's owed.

Floating around in the background is the potential for a fire sale acquisition by Vail Resorts, a massive US-based ski resort operator that has expanded into Canada, Australia and just this year, Switzerland. Vail representatives have not responded to repeated requests for comment.

Mazey recalls talking with the international operator when he was in charge of Ruapehu Alpine Lifts, but he believes it would be more interested in investing in the more reliable South Island ski fields, which operate 350 days a year. The idea of regularly and repeatedly closing down Whakapapa or Turoa on windy days would be anathema to Vail.

All but one of these solutions price in the impact of climate changes on capital investments. John Fisk agrees there is only so long we can continue skiing on Ruapehu – but he's not game to put a timeframe on that.

Was 2022's dearth of snow a portent of what's to come with climate change? "It's an example of what La Nina does. The warmer, wetter conditions, were certainly not conducive to snow this year, were they?

"For the longer term, climate is something that any operator would need to be aware of. And I know that Dave Mazey has been giving this a lot of thought. The solution to date has been the significant investment that's been made in snowmaking.

"In the future, it's going to be a mix of snowmaking higher up the mountain, and a utilisation of more of the ski area that the Department of Conservation has granted access to, in a way that uses some of the higher ground than what is being utilised today. Because, the long term of skiing in places like the Rock Garden is going to be harder to maintain in the future. But there is still a significant terrain up higher that is still in the ski zone, that could be utilised."

What is the one remaining solution, that wouldn't entail skiing into the teeth of the climate storm? It is, of course, shutting down the mountain's ski fields entirely – and that's a grim economic scenario.

Shutting down the ski fields

After so many generations of skiing on Whakapapa and Turoa, it's difficult to conceive a future without ski lifts dotting the slopes. And it's expensive to conceive that future.

"The worst possible outcome here is liquidation," Fisk says, "because it would just crystallise significant costs for make-good, if everything had to be removed from the mountain.

"There's probably about $50 million of make-good costs for the infrastructure that Ruapehu Alpine Lifts has on the mountain.

"If you look at all the lifts on the mountain, for example, that would mean taking down the towers and the ropes, that would mean removing the concrete foundations. There's a significant amount of work that would be involved here to actually restore the place to the state it was before those structures were installed. So there's about $50 million there.

"There's also 48 buildings on the mountain related to the ski clubs. The cost to remove those, because the ski clubs wouldn't be able to exist if the licence was cancelled, is about $30 million.

"And then you've got all the equipment that has been put there by The Lines Company to supply electricity to the mountain – removing that is not an easy job either. So if you had to return the mountain to its original condition, it's at least $100 million, and it would take a number of years to actually complete that work."

That $100-plus million is on top of the company's $44.3 million debts, discovered in the first week of the administration. And Fisk is yet to place a value on the 14,000 life passes. For now, they've been given a paper value of $1 each, but he acknowledges that if they were voided, the administrators would face court action.

Their owners typically paid $2000 to $4000 for them, but the compensation value might depend on factors such as the age of the holder – the passes owned by older skiers might be deemed to have less value in them than those held by younger skiers. Even valuing them conservatively at $2000 each, that's an additional $28 million liability.

Closure would also impact on the local economy. Communities such as Ohakune and National Park go from zero to hero in the ski season; their retail, hospitality and accommodation businesses are entirely dependent on Ruapehu tourism and the seasonal workers who flood the district. The public infrastructure, too, is paid for by the rates on holiday homes and businesses.

Fisk says: "The worst possible outcome here is liquidation."