It was an unusually warm and sunny morning when the people of Fishguard in north Pembrokeshire, Wales, arose on February 22 1797. Little could they have realised that over the next three days, their local area would play host to what is now described as the “last invasion of Britain”.

The story began during the summer before. French military leader General Louis Lazare Hoche and Irish revolutionary Theobald Wolfe Tone had planned a French expedition to Ireland. They wanted to assist the Society of United Irishmen, an organisation seeking Irish independence, in driving the British out of Ireland. But plans were abandoned due to stormy weather.

Hoche was undeterred, however, and put together another expedition. This time though, he wanted to rouse the British into rebellion against the crown. One of the French armies, the Légion Noire, was led by an Irish-American, Captain William Tate, who had gained military experience during the American War of Independence.

Tate was sent with four ships to Bristol, then Britain’s main port in the transatlantic slave trade. While there, his soldiers were supposed to goad Bristolian sailors into mutiny before spreading insurrection and chaos to London.

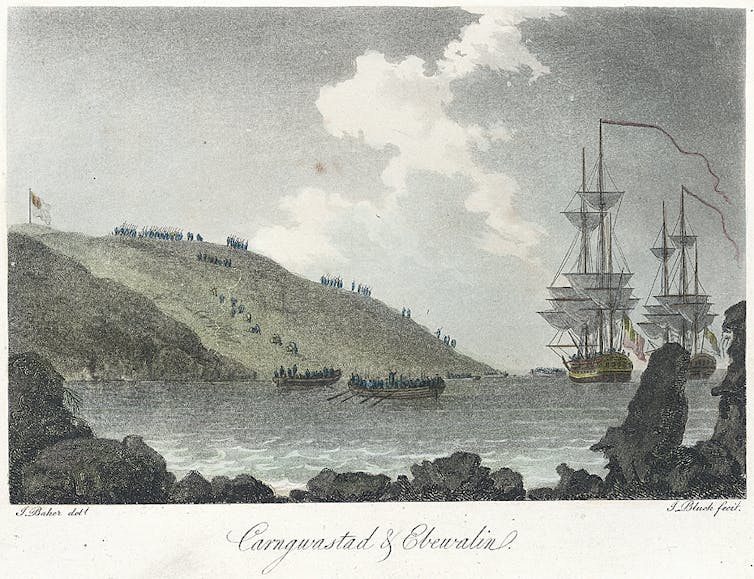

For several days in February 1797, blustery winds prevented Tate’s fleet from sailing up the Bristol Channel. Eventually, they gave up and searched for an alternative landing place. Heading west, they reached Pembrokeshire on Wednesday, February 22.

Tate’s army of 1,400 men, which consisted of 600 soldiers and 800 prison inmates, disembarked below Carreg Wastad Point near Fishguard. Overnight, he set up headquarters in a nearby vacated farm and, as planned, his ships departed. Next, Tate sent his soldiers out to collect supplies and announce the arrival of the French liberators from English oppression. It was from that point that everything fell apart.

Tate’s starving soldiers assaulted local people, ransacking their houses. Legend has it that some cooked geese in butter which is said to have resulted in serious food poisoning and may have contributed to subsequent French casualties.

Throughout the night, locals whose houses had been raided sought shelter with neighbours and word of the French invasion spread. Thomas Knox, a local commander, was attending a party nearby when he heard what had happened. He was slow to gather his men due to a lack of military experience. By Thursday, he had assembled the Fishguard Fencibles, but lacking resources and feeling overwhelmed, he retreated south towards Haverfordwest to wait for reinforcements.

Much more decisive was John Campbell, Lord Cawdor, who was at his country estate 60 miles away. He marched two local militias to Fishguard and on the way picked up Knox and the Fencibles. They finally reached the town late on Thursday. Their combined strength never amounted to more than 700 men. But there were several factors that eventually tipped the scales in favour of the Welsh defence force.

Against French expectations, the people of Pembrokeshire did not welcome the invaders. Several civilians armed themselves with pitchforks and scythes and small skirmishes occurred between individual farmers and soldiers across the area. Plundering cottages, some of the French soldiers happened upon barrels of wine salvaged from a Portuguese shipwreck. They got uproariously drunk and became incapacitated as a result.

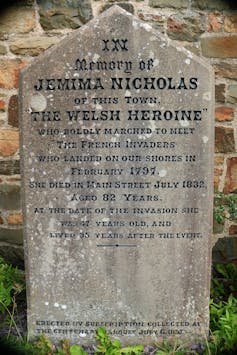

Local legend has it that Jemima Nicholas, a cobbler, singlehandedly rounded up 12 drunk soldiers and locked them up in St Mary’s church in Fishguard. Unfortunately, it is impossible to verify this story due to a lack of contemporary sources.

Meanwhile, morale collapsed among the French soldiers as they found themselves marooned on hostile territory. Cut off from reinforcements or rescue, Tate saw no other choice but to send two officers to Fishguard seeking conditions of surrender.

It is said the treaty was signed in the building that is now the Royal Oak pub. Lord Cawdor bluffed his way through negotiations, not letting on that the Welsh troops were outnumbered.

To ensure a successful surrender the next morning, Cawdor encouraged the townspeople to witness the French assemble on nearby Goodwick beach from the hill above. He wanted the distant crowd to appear to the invading French like thousands of soldiers to discourage them from attempting one last desperate fight. According to legend, it was mostly the women’s traditional red flannel shawls that gave the civilians their military appearance.

Over the next century, Jemima became known as Jemima Fawr (Jemima the Great) and was part of the folk culture around the invasion. During the centenary celebrations, enough money was collected for a stone to be placed in her memory at St Mary’s churchyard.

For the bicentenary in 1997, Fishguard held a full-blown reenactment. Yvonne Fox, a local woman, played the role of heroic Jemima and did so until her death in 2010. Fishguard continues to commemorate the invasion to this day.

Another lasting legacy was the creation of the Last Invasion Tapestry by local women, which tells the entire tale in Welsh and English. It is 30 metres long, took four years to complete and is housed at Fishguard town hall.

Naturally, Jemima the Great and the red-cloaked women of Pembrokeshire take pride of place in the design.

Rita Singer receives funding from the European Regional Development Fund through the Ireland Wales Cooperation Programme as part of the Ports, Past and Present project team. She has also received funding from the DAAD, AHRC and NLHF.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.