An enormous plume of magma over a thousand miles across is slowly but steadily rising underneath Mars' Tharsis volcanic region and could one day provoke a mighty eruption from the solar system's tallest mountain, Olympus Mons.

At 13.6 miles (21.9 kilometers) tall, Olympus Mons climbs so high into the Martian sky that its caldera pokes out of Mars' atmosphere and into space. Olympus Mons is joined by three other large volcanoes in the Tharsis region: Ascraeus Mons, Arsia Mons and Pavonis Mons. All of these volcanoes have been dormant for millions of years, but that could be changing, new research suggests.

"Mars might still have active movements happening inside it, affecting and possibly making new volcanic features on the surface," Bart Root, an assistant professor at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, said in a statement. Root presented his team's discovery at the Europlanet Science Congress last week in Berlin.

The four volcanoes stand on the Tharsis bulge, a gigantic swelling on the side of Mars that is 3,000 miles (5,000 km) across and 4 miles (7 km) above its surroundings, not including the height of the volcanoes atop it.

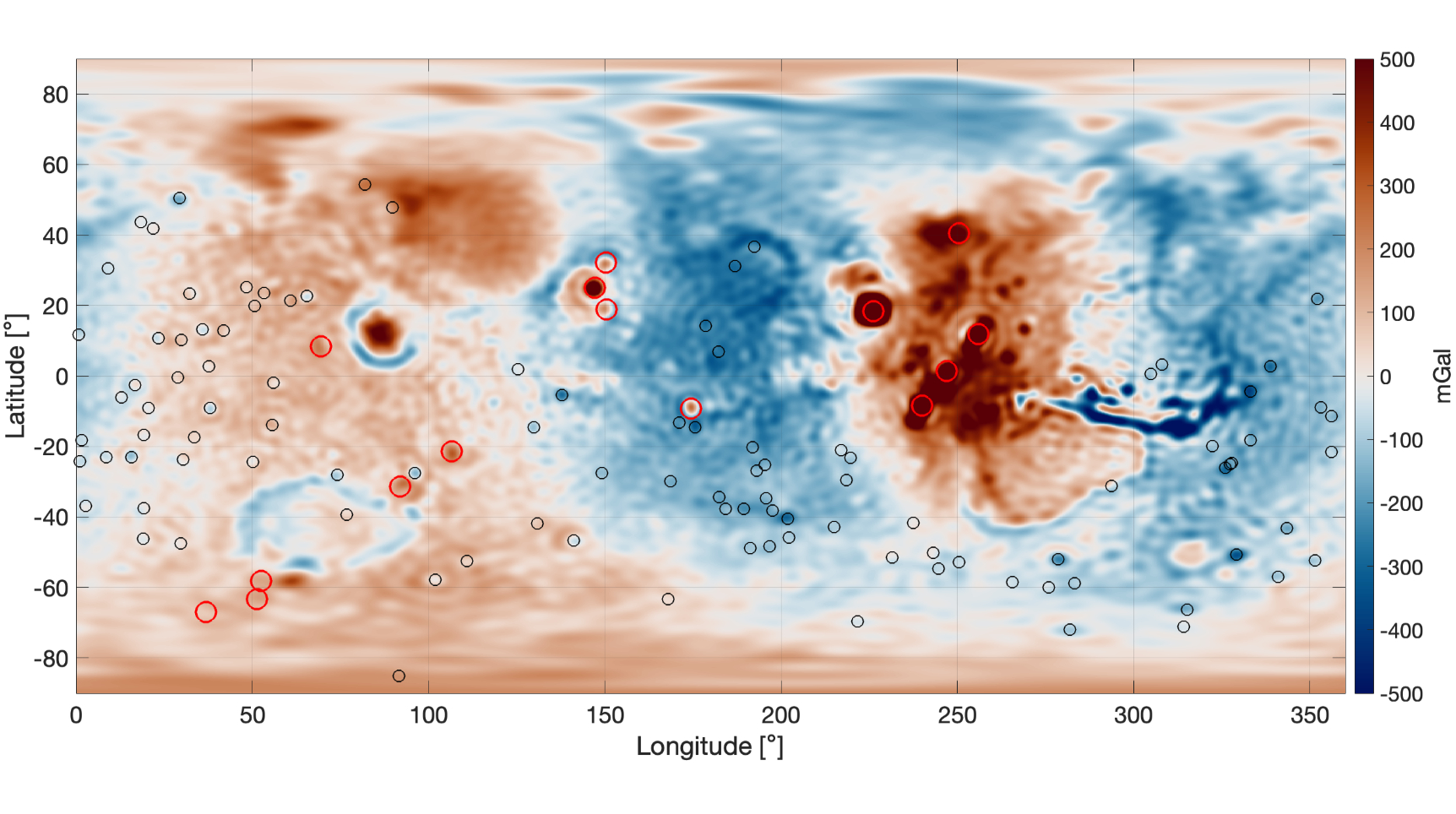

By carefully studying minute variations in the orbits of several satellites around Mars — such as Mars Express, the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter — Root and his colleagues were able to map the Red Planet's gravitational field. They found regions where the gravity was stronger and regions where the gravity was weaker.

Related: Magma on Mars may be bubbling underground right now

Combined with seismic measurements of the thickness and flexibility of the planet's crust, mantle and deep interior made by NASA's Mars InSight mission, the new findings reveal the complexities of the distribution of mass within Mars. Rather than being divided into neat layers like an onion, Mars' interior is lumpier, with various density anomalies.

Root's team found that beneath Tharsis is a vast region of weaker gravity, caused by a 1,100-mile-wide (1,750 km) region of lower density at a depth of 680 miles (1,100 km). They interpreted it as a huge plume of magma that's slowly working its way up from the planet's interior, to perhaps one day power the Tharsis volcanoes again.

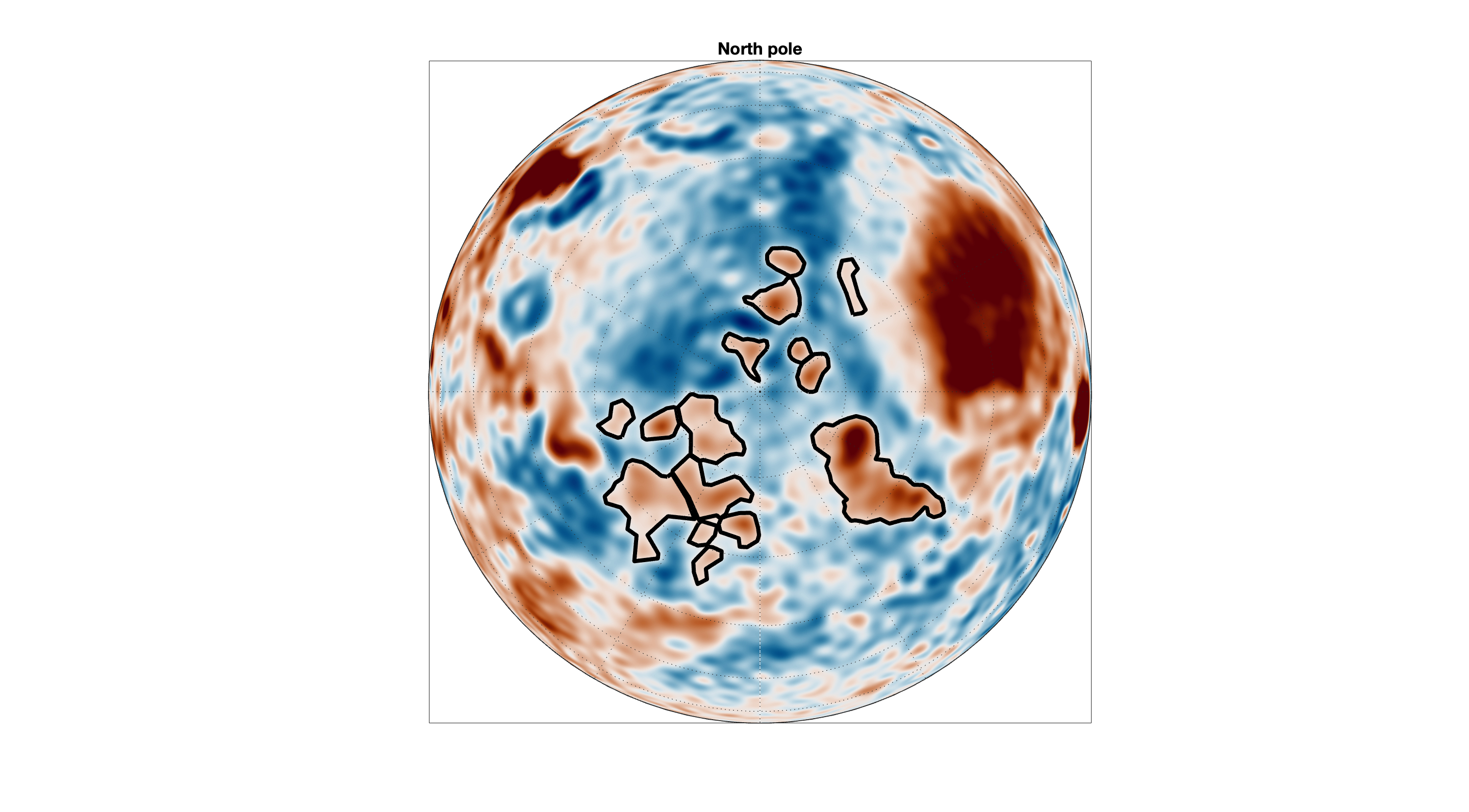

However, this mantle plume is not the only oddity that Root's team found from the gravity map. They also discovered more than 20 mysterious subsurface structures of various sizes — including one that resembles a dog — beneath Mars' northern hemisphere, where an ancient ocean once filled the lowlands. Unlike the mantle plume underneath Tharsis, these northern features are denser than their surroundings and have a strong gravitational pull. These structures are not visible from Mars' surface; they are buried deep beneath the sediments laid down by the ocean.

"These dense structures could be volcanic in origin or could be compact material due to ancient impacts," Root said. "There seems to be no trace of them at the surface. However, through gravity data, we have a tantalizing glimpse into the older history of the northern hemisphere of Mars."

A new mission would be required to learn more about these mysterious features. Root is part of a team proposing the Martian Quantum Gravity (MaQuls) mission, which would map Mars' gravity field in detail from orbit.

"Observations with MaQuls would enable us to better explore the subsurface of Mars," Lisa Wörner, a researcher at the German Aerospace Center, said in the statement. "This would help us to find out more about these mysterious hidden features and study ongoing mantle convection, as well as understand dynamics surface processes like atmospheric seasonal changes and the detection of groundwater reservoirs."