Ask Anthony Curis about Lantern, the new cultural and community hub in Detroit’s East Village, and he’ll give you a modest answer. On a rainy March afternoon in the Michigan city, known for its shifting fortunes tied to the automotive industry, he describes the architectural transformations redrawing the area, of which Lantern is part, as ‘a by-product’ of Library Street Collective, the gallery he founded with his partner in life and work, JJ Curis, in 2012. And yet, the many changes happening in Little Village, as the burgeoning creative district is now known, are both intentional and sweeping – and the Curises are behind them.

There’s the renovation of a 1912 church-turned-art gallery-and-library by Peterson Rich Office. Next to it, a McArthur Binion and Tony Hawk-designed skate park borders a sculpture garden dedicated to the visual artist Charles McGee, with landscaping by Manhattan-based studio OSD. An adjacent rectory was recast into a guesthouse and artist residency by Detroit practice Rossetti, with interiors by Holly Jonsson Studio.

Lantern: a new cultural and community hub in Detroit

‘When we first started meeting with the community members and stakeholders they said incredible, great – but we don’t want it to be an island, we want you to do more,’ Curis says about the response to their plans for the church, their first acquisition. The more they did, the more their list of collaborators kept growing. The Curises’ latest project, developed with OMA New York, transforms a collection of buildings that includes a former commercial bakery and warehouses into a mixed-use complex.

Sitting at the corner of Kercheval and McClellan avenues, the newly opened Lantern will house the HQ of two local art non-profits: Signal-Return, a community letterpress print shop, and Progressive Arts Studio Collective (PASC), which supports artists with disabilities and mental health differences. Organised around a courtyard, other tenants – artist studios, the music recording company Assemble Sound, plus retail spaces and more – round out a concept that sets out to serve the broader community.

In sync with the Curises’ and the Detroit art icon Charles McGee’s vision of improving the quality of life in the city through art, OMA has designed a building that reflects this idea of making a space that encourages creativity, without losing sight of the urban context. ‘In a city like Detroit, where a lot of the urban fabric has disappeared, it’s great to preserve a building like this,’ says OMA’s Jason Long, who led the design for Lantern.

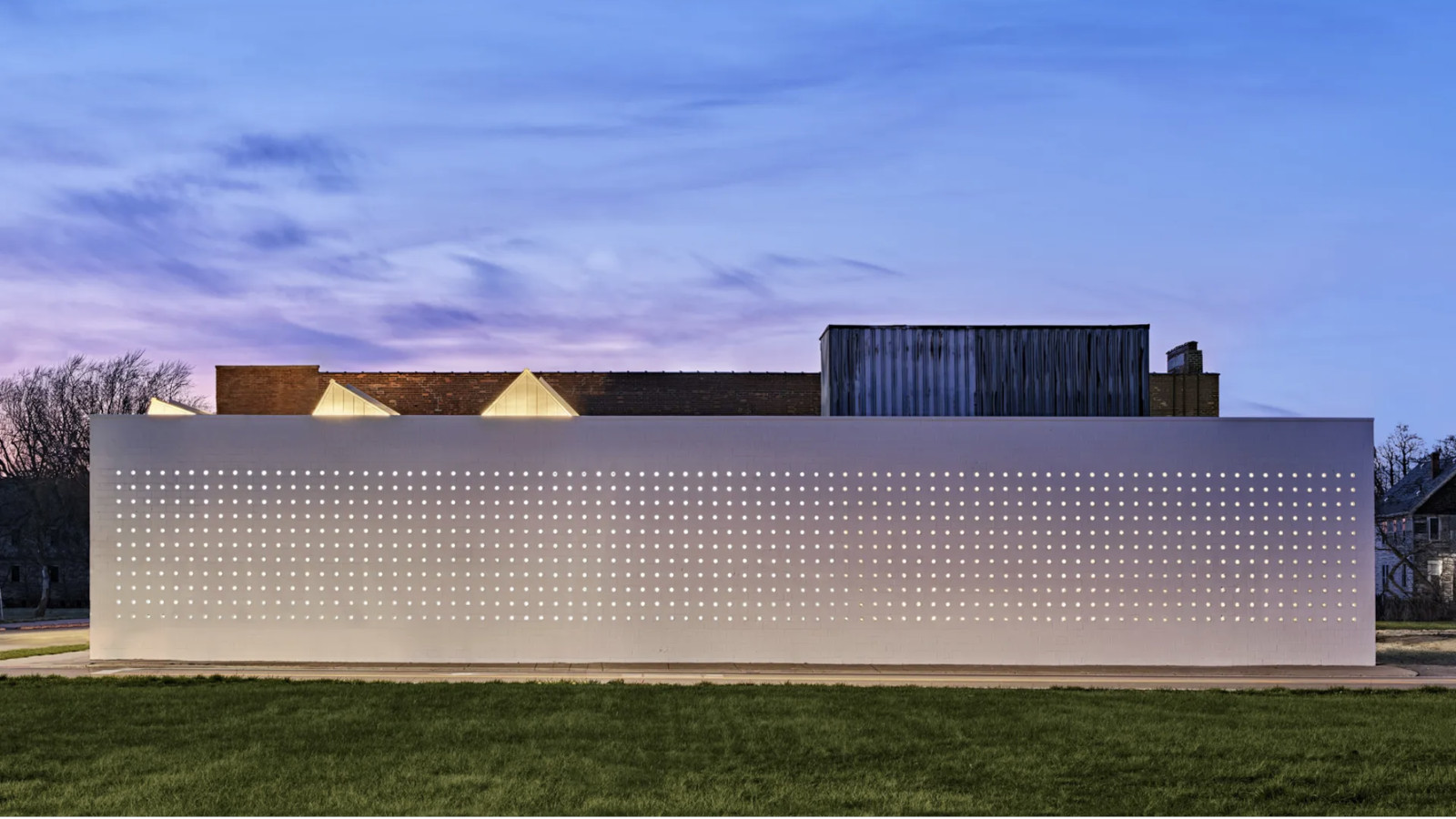

Though the space that became the courtyard was missing a roof and a wall on one side, Long decided to leverage the existing structure, warts and all. ‘The solid walls on the most prominent corner of the site are a very simple construction of concrete masonry units,’ he explains. ‘We thought that solidity was something to keep and at the same time we wanted to figure out a way to bring light into that part of the building – and some life into the façade itself.’

Long’s approach for these walls emerged while iterating different compositions of windows, ideas that never really felt right. ‘The existing openings within the building were so straightforward, clear and rational that doing something expressive just never seemed to work.’ He ultimately landed on drilling 1,500 holes into the surface and filling them with cylindrical glass elements. They perforate the façade with a muted transparency that hints at what goes on inside. Long sees it as ‘a somewhat light touch that at the same time has a dramatic impact.’

Not only has this façade been transformed from a solid barrier bordering the street to a textured invitation to explore Lantern, but the way the community will circulate and engage with the buildings has also been altered. By repositioning the main entrance toward the courtyard, formed from 2,000 sq ft of poured red concrete, OMA shields this public space from traffic while opening it up to an alley and the site beyond it. ‘That was our way of gesturing towards what we hope will happen as this area develops,’ offers Long. ‘We try to make all of our projects adaptable in certain ways, knowing that they might be used differently in the future.’

A living and breathing hub for the local community, Lantern is the newest example of how OMA leverages architecture as a catalyst for social change, creating the perfect foil for the Curises’ mission. Long adds, ‘Detroit is in a position to really experiment with urban conditions, culture and buildings. Hopefully, this intervention has been done in that spirit of experimentation.’

A version of this article appears in the June 2024 Travel Issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today.