There's a long history – even in the United States – of certain songs, deemed by those in power to be too inflammatory to be unleashed on the innocent ears of the public, getting banned from the radio.

The list of these banned songs is lengthy, and contains one very notable odd man out – Link Wray's Rumble.

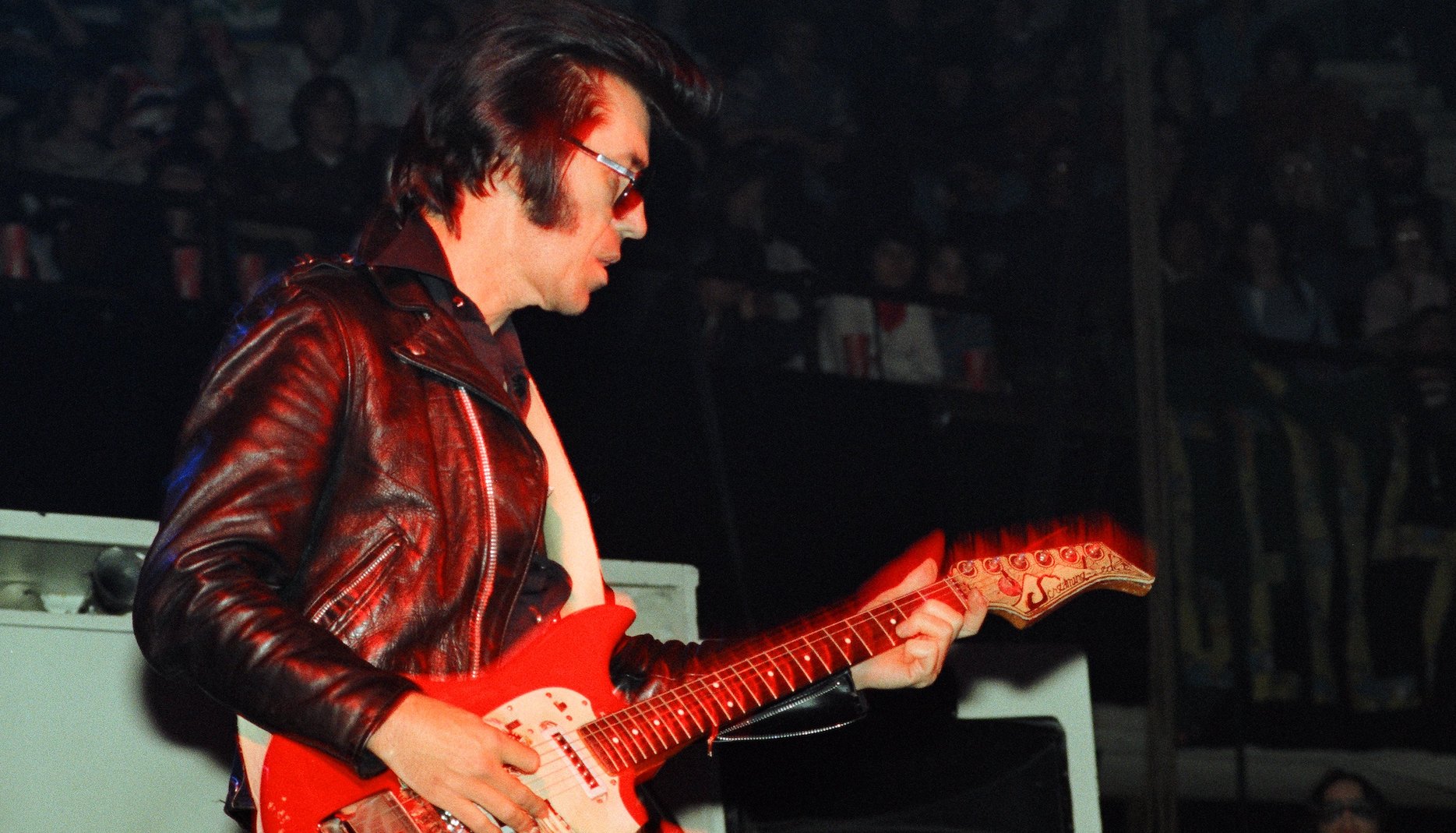

What sets Rumble apart from its fellow blacklisted tunes is that it has no words. The 1958 instrumental is all about Wray's ringing, gnarled, tough-sounding electric guitar power chords, played over the simplest of struts.

Rumble came out years before Keith Richards used a Maestro FZ-1 fuzz pedal for his bratty sound on the Rolling Stones’ earth-shattering 1965 smash, (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction, and long before even Dave Davies sliced a hole in the speaker cone of his Elpico guitar amp to achieve his savage tone on the Kinks' You Really Got Me (Wray beat Davies to that particular innovation, but more on that later).

Simply put, Rumble sounded like nothing that came before it.

Born out of a request to play The Diamonds' hit The Stroll (which Wray and his Wraymen band were unfamiliar with) at a dance, Rumble sprung from improvisation. Someone reportedly stuck a microphone too close to Wray's amp as he was playing his new riff, creating the song's signature distortion. From there, Wray once recounted, “The kids just went ape.”

In the studio, Wray famously poked dozens of holes into the speaker of his Premier amp with a pencil in an ultimately successful attempt to achieve that same distorted effect.

Rumble was released in 1958, the same year that radio giant Mutual Broadcasting System banned rock n' roll from its extensive network, casting the genre out as “distorted, monotonous, noisy music.”

Certainly, few hits of the era embodied the first and third of those adjectives more than Wray's oddball instrumental.

According to music journalist Jimmy McDonough, even the man responsible for signing Wray and releasing Rumble, Cadence Records head Archie Bleyer took a dim view of its aggressive sound and its subsequent impact, reportedly telling a friend, “I never liked Link Wray and the negative influence his music had on the young people of America.”

To add to its sins, in the eyes of those in charge, Rumble proved to be just as popular with young Black audiences as it was with young white listeners, at a time when politicians, judges, and law enforcement (especially in the South) were doing everything in their ample power to prevent integration.

Another issue for Rumble came from its name, which, at that time, was slang for a large fight – typically involving gangs.

As so often happens, the attempted suppression of the instrumental only made it more appealing to teenagers. Rumble became an unlikely top 20 hit even despite the blacklisting, and, more importantly, found its way into the ears of countless budding guitarists. The impact of the piece and its brash, distorted chord progression on the development of rock guitar playing simply cannot be overstated.

The Who's Pete Townshend dubbed Wray “the king,” saying at one point, “if it hadn’t been for Link Wray and Rumble, I would have never picked up a guitar.”

Bob Dylan called Rumble the “finest instrumental ever,” and Jeff Beck covered it dozens of times.

For It Might Get Loud, the guitar-themed 2008 documentary, Jimmy Page was filmed listening, and even playing air guitar to, the record.

“I listened to anything with guitar on when I was a kid that was being played,” Page tells his fellow It Might Get Loud co-stars, Jack White and the Edge, at one point in the film.

“But the first time I heard Rumble – that was something that had so much profound attitude to it… It really does.”