Scientists from the University of Miami are collaborating on an effort to address Florida's coral crisis as last summer's record-breaking marine heatwave severely impacted coral reefs in the Florida Keys, pushing them to the brink.

Axios reports that researchers are studying elkhorn coral colonies to develop solutions to the rising ocean temperatures caused by climate change and have suggested an unlikely solution: the research team plans to breed the Honduran corals with Florida's surviving corals to produce offspring capable of withstanding warmer temperature. The report details the process further:

"Led by Andrew Baker, director of the Coral Reef Futures Lab at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School, a team collected the elkhorn fragments from a reef in Tela Bay off the northern coast of Honduras, where the corals have somehow thrived in the same extreme heat affecting Florida's population. They hope to breed them with Florida's surviving corals — a technique called "genetic rescue" — to produce offspring able to survive warmer temperatures, Baker said in a news release.

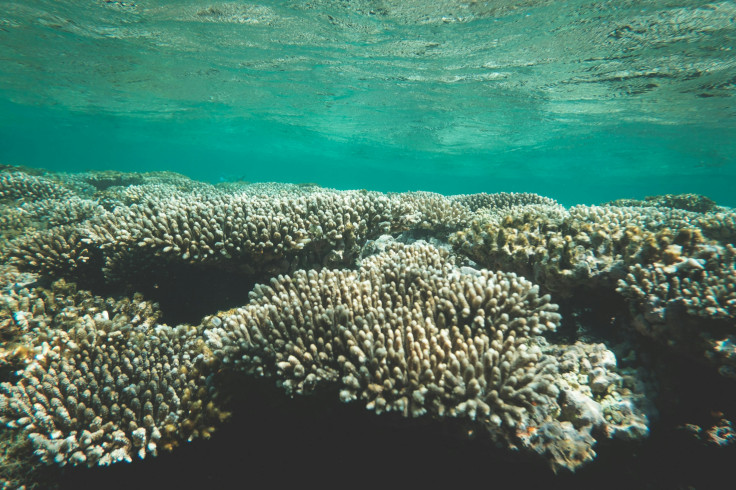

The extreme heat last summer resulted in the complete destruction of one reef and widespread coral bleaching, a phenomenon where corals turn white due to stress. This die-off led scientists to move thousands of corals to laboratories to protect them until temperatures normalized. As the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service reported back in August:

Essentially, corals around Florida are experiencing extreme levels of heat stress that have never been recorded before. All of the Florida Keys are at Alert Level 2 for bleaching conditions, which means severe, widespread bleaching and significant mortality are likely. Some sites have already been exposed to two times greater the amount of heat stress than when mortality is expected to begin, and so far, the most extreme heat stress is in the lower and middle Florida Keys.

Five years ago, the The Florida Aquarium's Coral Conservation and Research Center in Tampa participated in a coral cross-breeding project using elkhorn corals from Curaçao and coral sperm from Florida. Although the effort produced hundreds of offspring, they could not be released onto Florida's reefs due to genetic differences.

According to experts, the Honduran corals are more closely related to Florida corals, and scientists hope that the offspring from this current experiment will meet regulatory requirements for release into the sea.

Coral reefs are critical, as they provide shelter for a quarter of ocean animals and drive significant tourism in Florida.

© 2024 Latin Times. All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.