Those keen to make an environmentally-friendly buck out of repurposing pre-loved product should just take care whose trademark they're teasing | Content partnership

Businesses looking to turn a profit through upcycling branded goods are being warned they could be prone to legal action from image-conscious corporates, after Nike forced a US arts collective to pull its upcycled ‘Satan shoe’ range.

Upcycling – what’s not to like? The process of reworking an item to give it a new lease of life achieves not one but two of the three holy grail Rs of recycling – ‘reduce’ and ‘reuse’.

Whether it’s a keen sewer jazzing up an old jean jacket into a cool original item, or a secondhand store proprietor reupholstering an old armchair into a desirable piece of furniture, this reinvention of used goods to create a product of a higher quality or value than the original is surely nothing but awesome.

But there’s a catch, and it could be expensive. Businesses which go into upcycling could find themselves on the wrong side of intellectual property infringement law if they are repurposing branded goods in a way the original owner takes exception to.

Legal cases involving upcycling and trademark infringement are yet to crop up in New Zealand, but the poster child for the problem comes from the US – a law suit involving fitness clothing company Nike suing art collective MSCHF (‘Mischief’, get it?) over a potentially questionable shoe collection.

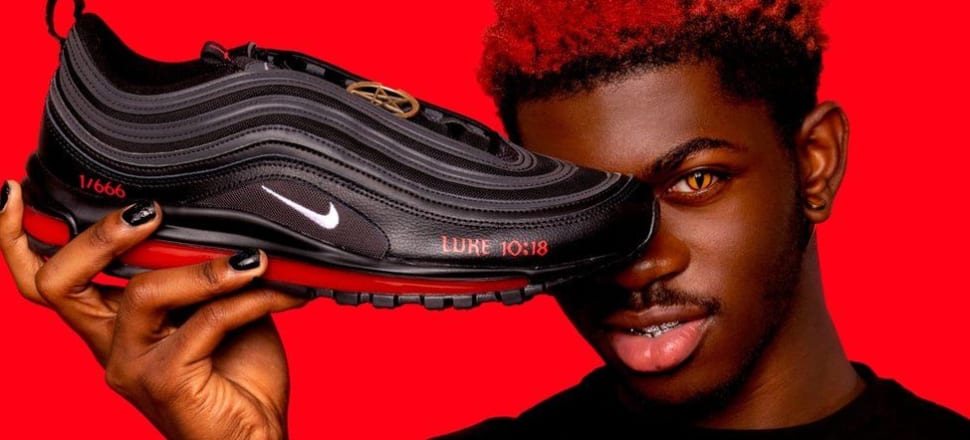

It started in 2021, when MSCHF (which prides itself on viral stunts and products which explore ideas and poke fun at stuff, according to this article in the New York Times) released an upcycled version of the Nike Air Max 97 sneaker, in collaboration with rapper Lil Nas X.

Dubbed the ‘Satan shoe’, the laces carry a bronze pentagram (five pointed star symbolising the five wounds Jesus Christ received during his crucifixion), the shoe’s tongue has an inverted cross; there’s also an embroidered Bible reference from Luke 10:18 (“I saw Satan fall like lightening from Heaven”), and an air bubble containing red ink enhanced with blood from MSCHF employees.

For good measure, there were 666 pairs of the sneakers made. They were put on the market for more than $1600 a pair and sold out within the first minute. Some pairs reached $6000 when onsold online.

Nike wasn’t happy. The company argued the modified sneakers infringed on its trademark and were “likely to cause confusion and dilution and create an erroneous association between MSCHF’s products and Nike”, according to court documents.

“Decisions about what products to put the “swoosh” [Nike tick logo] on belong to Nike, not to third parties like MSCHF,” Nike said.

The company also provided evidence through screenshots of social media comments that it had suffered a reputational hit, with potential and current consumers led to believe the Nike brand endorsed Satanism.

This case was eventually settled out of court, with MSCHF issuing a voluntary recall on the sneakers.

While New Zealand is yet to see a case like this, marketing and legal experts say businesses should be thinking about the possible ramifications of trademark infringement involving upcycling.

Bell Gully’s Partner and intellectual property lawyer Tania Goatley and her colleague Olivia Zambuto have looked into the issue.

Someone getting into upcycling as a hobby can breathe easy, Bell Gully’s senior associate Sebastien Aymeric says, because small-scale, non-profit-making activity for personal use won’t come under laws such as the Fair Trading Act.

Even if someone sells a modified pair of Levi’s jeans at a local market occasionally, or alters a small number of clothes to sell online, they’re unlikely to come under too much scrutiny, he says.

But if a person or business is looking to appropriate a brand’s image in their own product and onsell hundreds of those items, like MSCHF wanted to do, then they could get into legal trouble.

“If you’re a consumer modifying your own shoes for your own enjoyment, then you won't fall within the ambit of the Fair Trading Act,” Aymeric says. “But if your business is to modify shoes to on-sell them, and you do so in a way that potentially could be offensive or could damage the reputation of a trademark holder, then selling those products might confuse consumers or mislead them into thinking the brand owner has approved of, or is affiliated, with you.”

Bodo Lang, marketing expert and associate professor at University of Auckland Business School says large companies, such as Nike, will be hugely concerned about maintaining their image in the midst of upcycling.

“They’ve spent hundreds of millions of dollars on creating their brand, with young, fit, smiley people in their advertisements …They’ll be scanning social media to ensure their brand isn’t being used in a way they don’t like.”

That doesn’t mean all product alterations would receive this reaction. Another company, whose image might gel with the satanic imagery, might have welcomed the modified sneaker, as it could be seen to enhance their brand, Lang says.

But this was clearly not the case for Nike, which wants to maintain mass appeal and social approval.

“It’s the last thing Nike wants to be associated with. The brand has a big target market and cuts across a range of different types of consumers,” he says. “It’s a potential disaster for them.”

There are a number of different factors companies will be considering when looking at upcycled or modified products, Lang says.

One is the scale of production. Another is whether a product has been deconstructed in the upcycling process is also important.

For example, Lang says consumers will likely understand a clothing item made up of bits of material from a range of jean brands is not made by the original companies. But it wasn’t clear that the modifications in the ‘Satan shoe’ didn’t come from Nike itself.

A big brand considering legal action will also consider what damage the upcycled product has caused, Bell Gully’s Sebastien Aymeric says. This could be lost revenue due to offended consumers moving away from the brand, and reputational damage, including trademark dilution (loss of exclusivity), as with the ‘Satan shoe’.

Aymeric describes trademarks as “badges of origin”, which show not only which company produced the goods, but also give an indication of the quality of that product. In this way, altering one product could have a negative impact on the wider brand.

How New Zealand courts would treat an upcycling complaint is unknown – our law has not yet caught up with the upcycling phenomenon, Aymeric says.

Still, one legal defence to trademark infringement, which could apply in an upcycling situation is the ‘doctrine of exhaustion’. This means once a product is sold on the market by the brand owner who holds the intellectual property rights, the trademark rights can no longer be exercised.

This defence has been recognised under the Trade Marks Act and Copyright Act in cases allowing parallel importing, according to Goatley and Zambuto.

These laws, however, do not appear to consider upcycling and deal with the doctrine of exhaustion only in an importing context at an international level.

This means there is a grey area around where third parties fit into this in the context of upcycling, Aymeric says.

“Where the law is silent is on the issue of whether there is exhaustion of rights when the product is sold not to the end user, but to someone who is going to make changes to the product and the trademark itself and then sell it for a profit.”

There are no general provisions in the Trade Marks Act around whether a trademark owner could stop the middle person from making changes to their product and brand.

In this case, Aymeric says a company would need to fall back on a specific provision in the Trade Marks Act, which provides that it is an infringement for a purchaser of branded goods to use and modify the brand in a way that goes against any contract between the trademark owner and the purchaser.

One way this could be achieved is by a brand owner making clear, through the terms of use for its products, that items are not to be modified. This could mean adding disclaimers to sales tags for retail goods.

If the purchaser does breach those terms, this could count as trademark infringement and the brand owner then has legal recourse.

The advice from the experts? Bell Gully’s Tania Goatley and Olivia Zambuto say individual hobbyists who like to dabble in upcycling for personal use can rest easy. But businesses should approach trademark owners and consider asking permission to use their brand, or seek a trademark licence agreement.

Bell Gully is a foundation supporter of Newsroom.co.nz