One was asked to be an informant for Russia. Another's 16-year-old son was abducted as leverage. A third is still in Russian custody. Here are just a few portraits of prominent Ukrainian politicians, journalists, pastors and more who ended up on Russian lists for abduction, in an effort to strip Ukraine of its leaders.

___

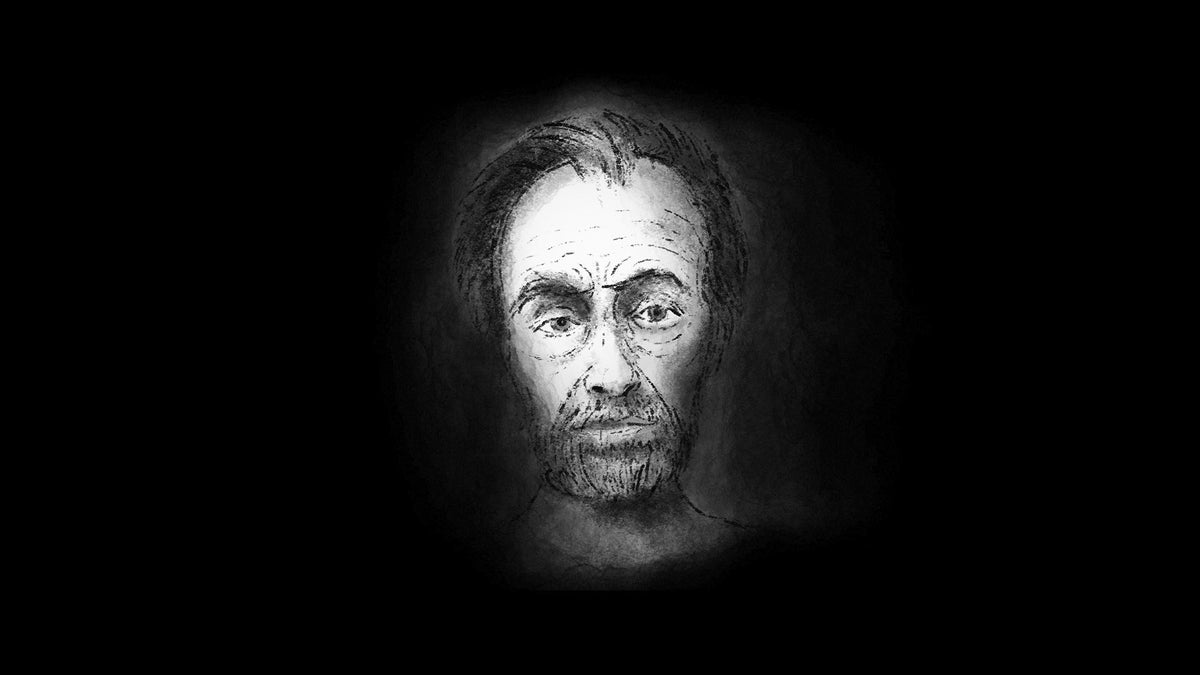

VIKTOR MARUNIAK

Two carloads of Russians came for Viktor Maruniak on his 60th birthday.

It was March 21. Maruniak, the head of Stara Zburivka village, in Ukraine’s southern Kherson region, said he and three other local men were taken to a nearby hotel, blindfolded, handcuffed, beaten, strangled and forced to strip naked in below zero weather.

“They’d point a gun toward our heads or toward the head of someone else, saying if you don’t say something, we will kill them,” Maruniak said. “Something was turned off in my head. It helped me survive. I was out of my body.”

After several days, he said, he was taken to a second detention center and tortured with electric shocks. They asked where weapons were stored. He said his captors’ vehicles and uniforms, along with documents he spotted and conversations he overheard, indicated that he had been taken by a special paramilitary police force under Russia’s National Guard.

To his surprise, he was released three weeks later, on the condition that he return to his village as an informant.

Instead, he fled to Latvia. He said he had nine broken ribs. Photographs taken after his ordeal show him thin and withered, with injuries to his hands, back, buttocks and leg. He looks with a level gaze at the camera, a man beyond shock or sorrow, as if nothing human beings might do to each other would surprise him anymore.

“They kept kidnapping people in my village,” he said. “Nobody knows where they are kept and why they are kidnapped.”

___

IHOR KURAIAN

When Russia invaded Ukraine, Ihor Kuraian buried his wedding rings for safekeeping and signed up with a volunteer military group in Kherson. Kuraian and his friends planned to storm a detention center where pro-Ukrainian activists were being held – an idea they later abandoned.

They had gathered 300 Molotov cocktails, 14 guns and a bag of grenades. When Russians found the weapons cache in his car, they tied him up and dragged him to a basement.

They interrogated him, twisted his fingers with pliers and beat him with a wooden club, he said. One man was beaten so badly his sternum fractured, and he died slowly, Kuraian recounted.

Under torture, Kuraian named another person involved in the plan to storm the detention center. When Russians forced him to call the man, he slipped false information into their conversation as a warning. The friend fled. Russians also took over his social media accounts to pump out propaganda.

“They wanted me to cooperate,” he said. “They even offered to make me mayor of Kherson. I refused.”

Kuraian was detained in Crimea and featured in a propaganda spot about prison conditions on Russian television. His family saw the video and lobbied for him to be released in an April 28 prisoner exchange.

“We were exchanged as you see in the movies,” he said. “Walk on the highway towards each other.”

___

VLAD BURYAK

Before the war, Vlad Buryak had the plump, carefree face of a well-loved child. Family photos show his father, Oleg Buryak, gazing at him with a happy smile in front of a Christmas tree.

All that changed at 11:22 a.m. on April 8th at the Vasylivka checkpoint between Melitopol and Zaporizhzhia, where Russians seized Vlad, then 16 years old, according to evidence gathered by his father, the head of the Zaporizhzhia district administration. As a guard looked on, Vlad called his father from a detention center and said he had not been beaten.

Buryak struggled to find words to help his son. “Do not get into conflicts, do not get nervous, do not get pissed off,” he advised.

Vlad had two questions for his father: “Why am I here?” and “When am I going to get out?”

As Buryak scrambled to negotiate his child’s release, the answer to the first question became clear: He was the reason Vlad had been taken. The Russians wanted local leaders like him to stand in front of a Russian flag and welcome them.

Three hard months passed before Vlad could tell the world all the things he hadn’t said on those calls with his dad -- about the torture he’d witnessed, the blood he’d mopped up, the man who broke down and tried to kill himself.

Finally, on July 7, Vlad was released. Buryak held his son in his arms.

“We are going home,” Buryak said. “Thank God.”

___

YEVHENIIA VIRLYCH

Yevheniia Virlych, editor of the local news website Kavun City, and her husband, Vladyslav Hladkyi, have spent years writing about Russian efforts to infiltrate Kherson and cultivate collaborators there.

When Kherson fell, they went into hiding and pretended on social media that they were in Poland. In fact, they were barricaded in a friend’s apartment with their cat.

They never went outside. They set up a code so they would know whether to open the front door. Three rings at the doorbell meant one friend; two rings and a knock meant another.

“I was afraid 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” Hladkyi said. “I had headaches. I’ve got a tic with my left eye.”

One July afternoon, Virlych was near the open kitchen window when she overheard two Russian soldiers asking around for her by name. She and her husband created fake Telegram accounts to book tickets on the next bus they could find.

Forty Russian checkpoints later, they were in Zaporizhzhia looking at a Ukrainian flag, wondering whether it was a Russian fake.

It wasn’t a fake. “It was real freedom,” Hladkyi said.

“I wanted to cry,” Virlych said.

___

ILYA YENIN

On a warm June night, a dozen armed men in balaclavas scaled the fence of Ilya Yenin’s house in Russian-occupied Melitopol. Yenin’s partner, Olga, went to the front door and was greeted by the glare of a flashlight. The Russians knew who they were looking for.

They hit Ilya a couple of times and asked where his brother Daniil was.

Both brothers were civilian activists, and Ilya helped found a group to deliver food and medicine to civilians. Daniil has been working with a different charitable fund that helps civilians and supports the Ukrainian military. He left Melitopol in early April, but his brother stayed behind to care for their grandmother.

Daniil waited for a call demanding ransom for his brother’s release, but none came. He began to wonder if Ilya had been taken just to scare — or punish — the people of Melitopol.

After three weeks in a detention center in Melitopol, Ilya was released. He has not dared to try to pass Russian checkpoints to leave occupied territory.

Daniil advises families of the disappeared to talk as much and as loudly as possible about it.

“If no one is looking for you, it means they can do whatever they want with you,” he said.

___

PASTOR DMITRY BODYU

Pastor Dmitry Bodyu was having coffee the morning of March 19 when his wife saw a group of Russian soldiers jumping over their fence.

A U.S. citizen, Bodyu founded the Word of Life church in Melitopol, an occupied city in southern Ukraine. The chilling thing was that the Russians seemed to know his secrets — not only who he was, where he lived and what he did, but also obscure details about his finances.

“Someone was talking about me. When they arrested me, they knew a lot of information about me,” Bodyu said.

In detention, his daily interrogations were a battery of accusations, all of which he said were false: You are helping the Ukrainian military. You are organizing protests. You are a spy for the United States. He thought his captors — some of whom he said wore uniforms with markings of Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB — wanted him to spy for Moscow.

“I said, what kind of information do you want to know about the U.S.? Where the McDonald’s is?” he said. “You are talking to the wrong man.”

The Russians insisted they’d come to help Ukraine and wanted Bodyu to spread their message of liberation. He said he was not beaten but could hear others held in the basement cells crying and screaming in pain.

After eight days, Bodyu was released, but Russians kept him under surveillance. In April, he fled with his family to Poland through Russia. He said Russians seized his church and set up a base there, driving parishioners underground.

“It’s not safe,” he said. “But people still meet together and even make plans to celebrate Christmas!”

___

SERHII TSYHIPA

Serhii Tsyhipa, a blogger, activist and military veteran in Nova Kakhovka, in Ukraine’s southern Kherson region, knew the Russians were looking for him.

He went into hiding but kept posting updates about Russian forces and a barrage of anti-Russian messages, including a fantastical satire about a pigeon sent to assassinate Russian President Vladimir Putin. On March 12, he went out with his dog and never came back.

Around six weeks later, a thin, hollow-eyed Tsyhipa surfaced in a video on pro-Russian media. He trembled and he held his arm funny. He regurgitated Russian propaganda. The video has gotten nearly 200,000 views on one YouTube channel alone.

His stepdaughter Anastasiia watched with horror: What had they done to him? “It’s not normal, the way he’s talking,” she told AP.

Voice analysis experts with the Ukrainian police concluded that Tsyhipa had made the video under duress, according to a copy of their analysis obtained by AP.

In July, his wife, Olena, got a Telegram message from a man who claimed to be a Russian agent. He told her to bring Tsyhipa's clothes and passport to a checkpoint in Russian-held territory, where her husband would be returned to her. Olena thought something was amiss: If she or a friend went for the handover, would they be taken too?

Tsyhipa’s family has reached out to lawyers, NGOs, international organizations, journalists and every Ukrainian authority they can think of, and European officials have publicly lobbied for Tsyhipa’s release. But nothing has worked.

“I asked them to put pressure on Russia to release political prisoners,” Olena said. “I think there are many people like my husband.”