Kanelkakor are Swedish cinnamon butter cookies. Almost every year at Christmas, I make these round, brittle shortbreads rolled in a generous coating of cinnamon and sugar, along with a handful of other cookies my late mother-in-law Betsy was famous for. She'd bake astonishing quantities of cookies each holiday season, giving all but a few tins away to everyone she knew.

Whenever I take that first bite of Kanelkakor — its crunchy, caramelized exterior crumbling into buttery, cinnamon-tinged sweetness — I am briefly transported to Betsy's carpeted living room with its pink upholstered couch and restored wood tables loaded with knick knacks. It's Christmas Eve, and the house smells like roast something mixed with buttery pie crust. We sip champagne from highly elaborate flutes, dreading the midnight mass she's goaded us into attending. I park myself in the upholstered rocker strategically in between the little bowl of sugared pecans and the cookie tin containing the most Kanelkakor. The light seems too low for a group who theoretically plan to stay awake into the wee hours.

This memory washed over me after I interviewed Rosie Grant, the Los Angeles-based, part-time librarian and TikToker who created the viral platform @GhostlyArchive, in which she recreates recipes etched into people's gravestones. So far Grant has documented 25 recipes, which includes interviewing the families of the deceased and, in a handful of cases, recreating the recipes and taking them back to the graveyard to eat them in the presence of their creators. Many of the recipes have been desserts, and nearly all the graves, dating as far back as 1994, belong to women.

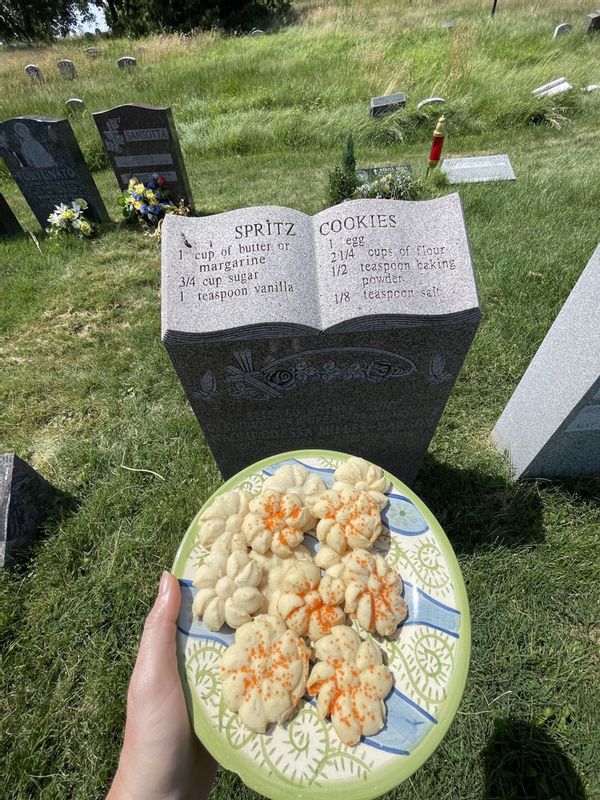

Grant started the project just over two years ago, initially as a grad-school social-media assignment documenting cemetery life and upkeep at Washington D.C.'s Congressional Cemetery. But then she heard about the grave of Naomi Odessa Miller Dawson in Brooklyn, which was inscribed with a recipe for Dawson's favorite spritz cookies. Grant decided to bake and document the gravestone recipe on TikTok. It went viral overnight, amassing a million likes. Soon she learned about other families who'd engraved their loved ones' headstones with their favorite recipes, thanks in part to improvements in gravestone technology that enable more personalization. Now with 195,000 TikTok followers and over 8 million likes, Grant is considering turning the project into a cookbook.

"What's that phrase? Every time someone dies, it's like a library dies," Grant said. "There's so much food knowledge and history in each person. That's been such an interesting part of this project, the number of stories I'm getting about people. Looking through the comments on TikTok, everybody has a personal food story: 'My mom, dad, or grandma makes this. My dad passed away and I never got his barbecue recipe. I wish I'd interviewed him.' These food legacies and histories we might take for granted are so precious."

Eating and dying are two things we human beings all share, though Americans in particular are squeamish about talking openly about the latter. Bridging the two by, say, talking about a recipe we'd put on our gravestones, can offer a more lighthearted entry point to the Death Positive Movement, which posits that people in society are healthier if they talk more openly about mortality and how they want to be memorialized.

"There's this idea of what if we had conversations of like, how do we want to be remembered?" Grant said. "What do you want your memorial to look like? Food is such an easy lens for that."

Emerging from a global pandemic has no doubt brought death to the forefront of our collective consciousness as a culture, she said.

"We all experienced this collective, insane thing that we don't know what to do with," Grant said. "We went back to the 'norm,' whatever that is, but that's still there! I think that's why (@GhostlyArchives) is resonating. It uplifts the beautiful, lighter side of this huge, momentous thing like dying through food memories and cooking."

The most recent grave Grant visited belongs to Annabell Gunderson, who lived in Northern California and was active in the civil service, including as a volunteer firefighter with her husband. Her tombstone features her snickerdoodles recipe, the secret of which is to "keep dough fluffy!" it reads.

"Annabell's daughter told me that she was a very giving person," Grant said. "Her recipe makes, like, a thousand cookies — it calls for five and a half cups of flour — so it was meant to be shared. Annabell's daughter told one story of the all-volunteer fire department coming to the house in the middle of the night and her mom was handing out food, including these cookies. So there was always that sense of giving. How beautiful that it continued in her death through sharing this recipe."

I couldn't help but find similarities to Betsy, a speech therapist who was active in her church and boundlessly generous until her untimely death from ovarian cancer, just before Christmas in 2009. For months thereafter, we felt swallowed by the immensity of our grief. Eventually, baking her cookies became a sensory conduit that ferried us back to our richest memories of her, flitting around her cramped, cluttered kitchen. Her recipe cards, written in loopy script and stained from use, are like little gifts.

"That's how I see a gravestone recipe, a gift," Grant said. "There's another saying, that you die two times: first when you die and second the last time someone says your name. A cemetery is the last public memorial to someone you might not know otherwise. When you read the inscription on their gravestone, it is a public memory to different individuals who are normal people. It keeps their memory alive."

Betsy was cremated and buried in the front yard of her church beneath a small memorial plaque. You won't find a recipe for her Kanelkakor there, but I firmly believe she'd want you all to have it anyway.