Judging from the tenor of the limited headlines and social media posts about "Surviving R. Kelly: The Final Chapter," one might conclude that its main purpose is to confirm the most disgusting suspicions about convicted serial sex offender and child predator Robert Kelly.

As a media professional who understands the importance of pageviews and traffic, I get why brief distillations of the two-night conclusion would highlight the most gut-churning aspects of victims' court testimony and video evidence. It's the type of abuse that embosses itself onto one's psyche and, although it makes me miserable to say it, will probably fertilize an entire section of Dave Chappelle's next routine.

Unearthing never-before-revealed details about Kelly's ritualistic abuse tactics is not the reason this third and final entry in the "Surviving R. Kelly" docuseries is important. That should go without saying, but this remains a society where people still laugh at old sketches and more recent jokes about the singer urinating on a child. People need to be reminded that these crimes were committed against women who are still being hunted and publicly denigrated by Kelly's fans and personal network.

That 14-year-old girl in the infamous tape is now an adult in her late 30s who gave testimony at Kelly's 2022 trial, where he was found guilty on three charges of production of child pornography and three charges of enticing a child. She's identified in court transcripts as "Jane" and her decision not to use her real name is understandable. The women who revealed their names and faces in the first "Surviving R. Kelly" have been stalked, threatened and vilified to an extreme many of us couldn't imagine.

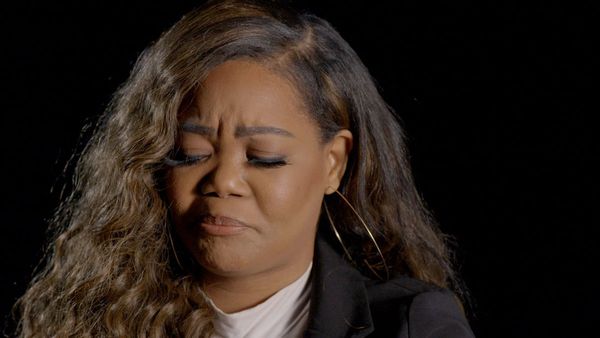

For corroborating dream hampton's work as a witness in the first episodes, back-up singer and dancer Jovante Cunningham says that in addition to being ostracized, she was doxed and her personal information was released online. Still, Cunningham refuses backing down and reveals what she did not in those first episodes, that Kelly abused her too.

In answer to the unasked question of why she withheld that information the first time, Cunningham says, "Who wants to be associated with this? This is not a badge of honor. It's not something that you gloat in. It's not something that you delight in. Who wants to be a part of a human trafficking ring, or even admit that that even happened to them?"

That statement, along with the myriad accounts of other survivors, psychologist and experts, reasserts this series' vital necessity as a document. This series achieved the unthinkable, finally penetrating the shield of enablers surrounding Kelly with such force that federal and state prosecutors couldn't ignore his crimes any longer. And these episodes train a magnifying glass on that extensive system of enablement, naming key people who worked for him, and pointing out that his record label's representatives and the music industry at large pretended Kelly's criminality either wasn't happening, or wasn't a big deal.

People need to be reminded that these crimes were committed against women who are still being ... publicly denigrated by Kelly's fans and personal network.

In this regard it also implicitly impugns the public, and rightly so, for downgrading his horrific predation to another example of celebrity misbehavior. As reductive as it may seem to point out that society bears some of the blame for Kelly's success as both a popular artist and a criminal, consider how many people knew about amply substantiated allegations that he made child pornography and still sang along to "I Believe I Can Fly" at their Sunday religious services.

Recall whether you regarded his marriage to 15-year-old Aaliyah in 1994 as a scandal – as many did, including the press – or a crime, which it was and is.

If the opening episodes of "Surviving R. Kelly" constructed the pathway for federal and state authorities to reopen cases against the singer and bring him to justice, its final hours provide cautionary exhibits and evidence of how dangerous rabid fandom can be.

That much broadcast widely last year in the form of two very high-profile exhibits of this in the form of the coverage of the Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial and the criminal case against rapper Tory Lanez, who was recently convicted of assaulting hip-hop artist Megan Thee Stallion with a firearm. In each case, fans treated the women at the center of the case as criminals and the slanderous jokes and threats made against them as entertainment.

Heard's negative differential in fame, popularity, and power in relationship to her ex placed her on the losing side in the public court of opinion. Megan Thee Stallion, although far more popular than Lanez, was disbelieved and ridiculed on social media by people taking Lanez's side, primarily consisting of Black men but with some Black women doing their share of emotional damage too.

Those women are famous. Kelly's victims, including their families, are everyday people caught in the net of an organized effort music journalist Jim DeRogatis correctly characterized in his 2017 BuzzFeed story as a sex cult.

Since the first "Surviving R. Kelly" debuted in 2019, the fathers and mothers of several of Kelly's survivors, and the women themselves, reveal that they've had to move from their original homes. Jerhonda Pace testifies that she was also advised to move out of concern for her safety in the final days of her pregnancy.

Azriel Clary, who initially supported Kelly in his memorably explosive CBS sit-down with Gayle King, subsequently escaped his clutches and conducted another interview where she admitted that nothing she said was true. Her father Angelo says one of the performer's associates set the family's car on fire in the hope of burning down their home in 2020; the perpetrator also poured gasoline around their house's perimeter to achieve that end.

So when we see Black women outside the courthouse claiming to support R. Kelly, including one who has tattooed his name across her chest, recognize that they are simply the most extreme versions of a fandom that is widespread on a passive level but still bolstered Kelly's ability to get away with exploiting underage girls and women – and, as we now know from court testimony, young men – for nearly a quarter of a century.

Kelly was found guilty on charges of federal racketeering and sex trafficking in 2022. He's still facing 12 state charges: 10 in Illinois and two in Minnesota. And it remains an astonishment to know that an extensively sourced, meticulously laid-out docuseries airing on a commercially supported basic cable network, one that centered Black women survivors of sexual assault, achieved this.

W. Kamau Bell, who shows up near the close of these episodes, credits "Surviving R. Kelly" for inspiring his 2022 documentary series "We Need to Talk About Cosby," Bell's critically acclaimed examination of our culture's fixation with Bill Cosby, who's faced more than three score accusations of sexual assault and abuse, was eventually convicted in 2018 on charges related to one of those case, only to be freed from prison on a technicality in 2021. He's planning to tour in 2023 despite facing a new civil suit tied filed by five women.

Kelly is still in prison serving a 30-year sentence, with additional time related to his child pornography conviction due to be added at another sentencing hearing, expected to take place in February. If "The Final Chapter" takes a victory lap at times, that's because it deserves to.

Radio DJ and fellow survivor Kitti Jones says as much. "Can we focus on the fact that this happened here, and these Black women were heard and they made history and they fought no matter what they were up against?"

If "The Final Chapter" takes a victory lap at times, that's because it deserves to.

We should, while also acknowledging, as the production does, that the work isn't done either in this case or in changing how the broader justice system deals with rape reporting and survivors. While hampton, survivors, and an array of experts praise the dedicated work of journalists, especially DeRogatis, who never stopped reporting on the case since the tape was brought to him in 2002, they also point out that the entire reason these charges stuck is that Kelly's crimes were prosecuted as a RICO case.

DeRogatis and others express admiration for the brilliance of that legal tactic, since that means Kelly wasn't simply charged with aggravated sexual assault, but with forming a criminal enterprise that allowed him to get away with it. That gave prosecutors the ability to call witnesses and victims who weren't specifically connected with crimes Kelly committed.

But the cold draft cutting this vindicating comfort is in knowing that the legal machinery for sexual assault cases still doesn't work as quickly and passionately as it does for racketeering. Clinical psychologist Ramani Durvasula, Ph.D., adds that the male victims coming forward also made a difference: "This became less a story of sexual assault, which is very female-identified in this case, and it just became a case of perpetration, that guy just harms."

Kelly is now behind bars. The survivors who testified, and those who came forward in previous episodes of the series but ultimately did not take the stand, can celebrate that. That statement also helps a person to understand why they remained nervous and uncertain until the moment the verdict was read.

"I feel the system has shown us a pat on the back, yes . . . but it took hell to get there," mused Faith Rodgers, who testified at Kelly's New York trial. "Let's not act like, you know, I didn't go to the police before trial." Then she asks, "Have we made history? Yes, but . . ." then she trails off.

Nevertheless, many of the interview subjects express how differently their testimony was treated now as opposed to 20 years ago, crediting the movement for changing the way people who come forward with assault allegations are treated in at least some corners of the justice system.

But the series leaves us with the sobering note that the people who aided Kelly in committing all of these crimes – who kept these women locked up against their will, threatened those he assaulted with harm after they escaped him, and committed other illegal acts in service to him – still walk free.

That should disgust us.

All four episodes of "Surviving R. Kelly: The Final Chapter" air Sunday, Jan. 8 from noon to 4 p.m. on Lifetime.