You know, it’s funny how you can remember some things, and some things you can’t. Memory has reduced “Forrest Gump” to a few lines of dialogue and the ubiquitous meme of Tom Hanks “running like the wind” blows down the country road outside his home in Greenbo, Alabama.

Forrest’s hometown isn’t real, but neither is much of anything else in this movie save for a few landmark historical moments. Hanks’ character meets three American presidents – John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon – and through digital wizardry that looks terrible now, we watch him treat shaking hands with history as an inconvenience. (We've since come to understand this as metaphor.)

He loses his best friend Benjamin Buford “Bubba” Blue (Mykelti Williamson) while serving in Vietnam. Later we see Forrest lose his dear Momma (Sally Field) to cancer and the girl he’s always loved, Jenny (Robin Wright), to AIDS.

Remembering the 1994 movie’s specifics isn’t important since, as Hanks pointed out in a USA Today article marking its 25 anniversary, it’s never gone away.

And Hanks himself, that paragon of niceness, has only become a bigger avatar of American identity. He won his first best actor Oscar for his work in “Philadelphia” and his second for this. Of the two it is understood that Robert Zemeckis’ slow-witted hero launched him to icon status. Hanks’ “Philadelphia” character, an HIV-positive attorney suing his former firm for wrongful termination, was a more challenging performance. It was also a sympathetic examination of a shameful time that still made people uncomfortable in 1993.

“Forrest Gump,” meanwhile, is entirely devoted to making white Americans feel comfortable — about themselves, and about what they represent to the world. Zemeckis’ adaption of Winston Groom’s novel presents the 20th century through the simplest lens as it was lived by a man with an I.Q. of 75 who loves his Momma, follows directions to the letter, and is essentially good.

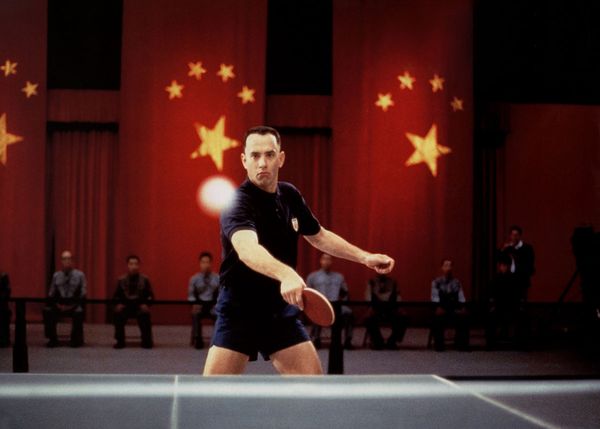

The film’s running joke is that Forrest happens to stumble into moments of great consequence, usually as a witness but sometimes as the accidental force that pushes history along.

Five years ago major news organizations like CNN, the Los Angeles Times, and USA Today marked the movie’s 25th anniversary with coverage remarking on the film’s polarizing nature in the most neutral terms: it’s either heartwarming or manipulative, conservative or apolitical, an introduction to history, as CNN describes it, or an airbrushing of it.

Other culture writers were less diplomatic, citing the troubling portrait of Robin Wright’s Jenny, the love of Forrest’s life. One of the many reasons it made the National Review’s list of top conservative moves of all time in 2009 is the film’s tacit implication that Jenny catches HIV as the result of her sexual and political liberalism.

A turning point in Alan Roth’s script is when she turns down Forrest’s marriage proposal after living with him for a while. She has sex with him and disappears afterward, resurfacing years later with their child and news that she's dying.

Murray continues: “But to a large extent, “Forrest Gump” isn’t really an expression of values or a guide to a better life. It’s more a poignant, reflective look at how this country survived the tumult of the ’60s and ’70s by rebooting itself every few years, then running full-speed ahead into something new.”

IndieWire’s Eric Kohn had another take. “[V]iewed 25 years after its release lead to box office success and six Oscars, it remains a bad movie that gets worse with age, and much scarier than its cozy reputation suggests.”

I cite these excerpts about “Forrest Gump” less out of a matter of echoing them than to observe that at 30, the most alarming part about the movie isn't its historical or political elision but in the ways present-day America is sinking to meet the film's mythical version of it.

As much as Forrest is a know-nothing, except when it comes to knowing what love is, he’s also a do-nothing when it comes to acknowledging systemic wrongdoing.

To him, the legendarily bigoted Alabama Gov. George Wallace is an angry little man standing in the way of some people, not a national politician Wallace symbolically trying to block the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963. The Black Panther Party is a place where a furious Black man bellows at him about stuff while Jenny's no-good boyfriend punches her. The film mutes the Black stranger's grousing about inequality and the government's warmongering because Forrest, in military dress, must save Jenny from the dirty hippie.

“They'd all dress up in their robes and their bedsheets and act like a bunch of ghosts or spooks or something. They'd even put bedsheets on their horses and ride around,” he says in his guileless narration.

She did that, he says, “to remind me that sometimes we all do things that, well, just don't make no sense.”

In the "see no color" 1990s liberal America sold itself on the false idea that bigotry and racist terror were such distant relics of a bygone age that this could be played for laughs. The idea that groups like Moms for Liberty and other conservative activist groups would threaten school boards, force a curtailing of access to literature, and push to excise accurate teachings of history from public education was inconceivable. We couldn't even picture a future time when provable facts about our nation's history would be rewritten to protect some of us from being offended by nasty truths.

Three decades later, this is where we are: A small library in Donnelly, Idaho, has been forced to become “adults only” to comply with House Bill 710, passed by the state’s Republican legislature. The law requires all libraries, public and private, to designate an “adults only” section to which they can relocate a book within 60 days of receiving a written complaint about it. Donnelly’s library is too small to accommodate a separate section, so it made the whole place “adults only.”

Ostensibly this censorship targets books with queer content but can easily be used to remove books that accurately depict American slavery, the Jim Crow era or any inconvenient truth, really. Any library that doesn’t comply could face a civil lawsuit under the law, along mandatory $250 fine for the library and plaintiffs could receive uncapped damages.

Only children participating in the library’s paid programming and whose parents sign a waiver will be given free access to the 13,000-item collection, the library’s director told Boise State Public Radio.

The law went into effect July 1, the same day Oklahoma’s Superintendent of Public Instruction issued a directive requiring all public schools to teach the Bible and the Ten Commandments – specifically, as he told PBS News Hour, “the role the Bible played in American history, dating back pre-Constitution . . . all the way up through Martin Luther King Jr. and civil rights movement.”

But probably not any version of that history that violates a law passed in May 2021 that prohibits public schools from teaching concepts that would cause students to “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress” because of their race or gender. That would preclude an honest rendering of the Christian nationalist foundations of the Klan and its vision of a white Protestant America.

I guess if teachers ever teach that inconvenient bit they can skip the part about the lynchings, intimidation, political disenfranchisement and property theft and tell the kids the Klan was doing things that just don’t make no sense.

Less than 1% of venture capital funding goes to businesses owned by Black and Hispanic women, and only 2% of investment professionals at venture capital firms were Black women in 2022, according to studies cited by Associated Press coverage of the case.

The suit is being brought by the American Alliance for Equal Rights, the far-right group behind the Supreme Court case that ended affirmative action in college admissions. It is one of many using civil rights law to claim that the Constitution is colorblind and any institutional practice or program dedicated to leveling the playing field for non-white people discriminates against white people. And these are only the most recent developments in a years-long push to erase the historical accounts of and literature by and about marginalized people.

Forrest sees everyone as equal. He couldn't walk, but, by the grace of being chased by a few local bullies who grew up to be violent rednecks, managed to run his way out of his leg braces. He ran his way into a college football scholarship, where he probably didn't learn anything. He dashed his way out of poverty. So what's stopping the rest of us?

Let me be clear: none of this is the fault of “Forrest Gump” or any single movie. (For what it's worth, in 2021 Hanks came out against educational whitewashing in a Times op-ed.) Zemeckis’ best picture winner is part of a long Hollywood tradition of looking at bigotry and segregation as all but solved or surmountable due to the grace and benevolence of individual white people.

But this movie exported a specific brand of American identity and our tendency toward historical avoidance around the world. Out of the $678 million the movie grossed worldwide, according to Box Office Mojo, nearly $348 million came from the international box office. That's more than half.

Forrest Gump is the same as Miss Daisy or Emma Stone’s Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan in “The Help,” only he is the feather we see floating through the air in his movie's opening credits. By just drifting through the tumult and chaos of society, doing what he’s told, and through sheer dumb luck, Forrest Gump becomes one of the richest people in America.

“As I see it,” Groom told the New York Times back in 1994, “it's a story about human dignity, and the fact that you don't have to be smart or rich to maintain your dignity even when some pretty undignified things are happening all around you."

That view absolves us of trying to understand the systemic source of those indignities as something other than unkindness. It’s a tip of the hat to willful blindness, lack of critical thought and historical illiteracy.

Groom took issue with screenwriter Eric Roth’s rewrite of his book’s line about chocolates, but another “Forrest Gump” catchphrase the screenwriter originated himself is more appropriate today than ever: “Stupid is as stupid does.” With a box of mixed candy, we may not know what we’re going to get. With our aimless drift toward mass ignorance, we do.

"Forrest Gump" is streaming on Paramount+.