Mark Monday, April 8, 2024, on your calendar as "Solar Eclipse Day," for if the weather is fair, you should have no difficulty observing a partial eclipse of the sun from much of North America.

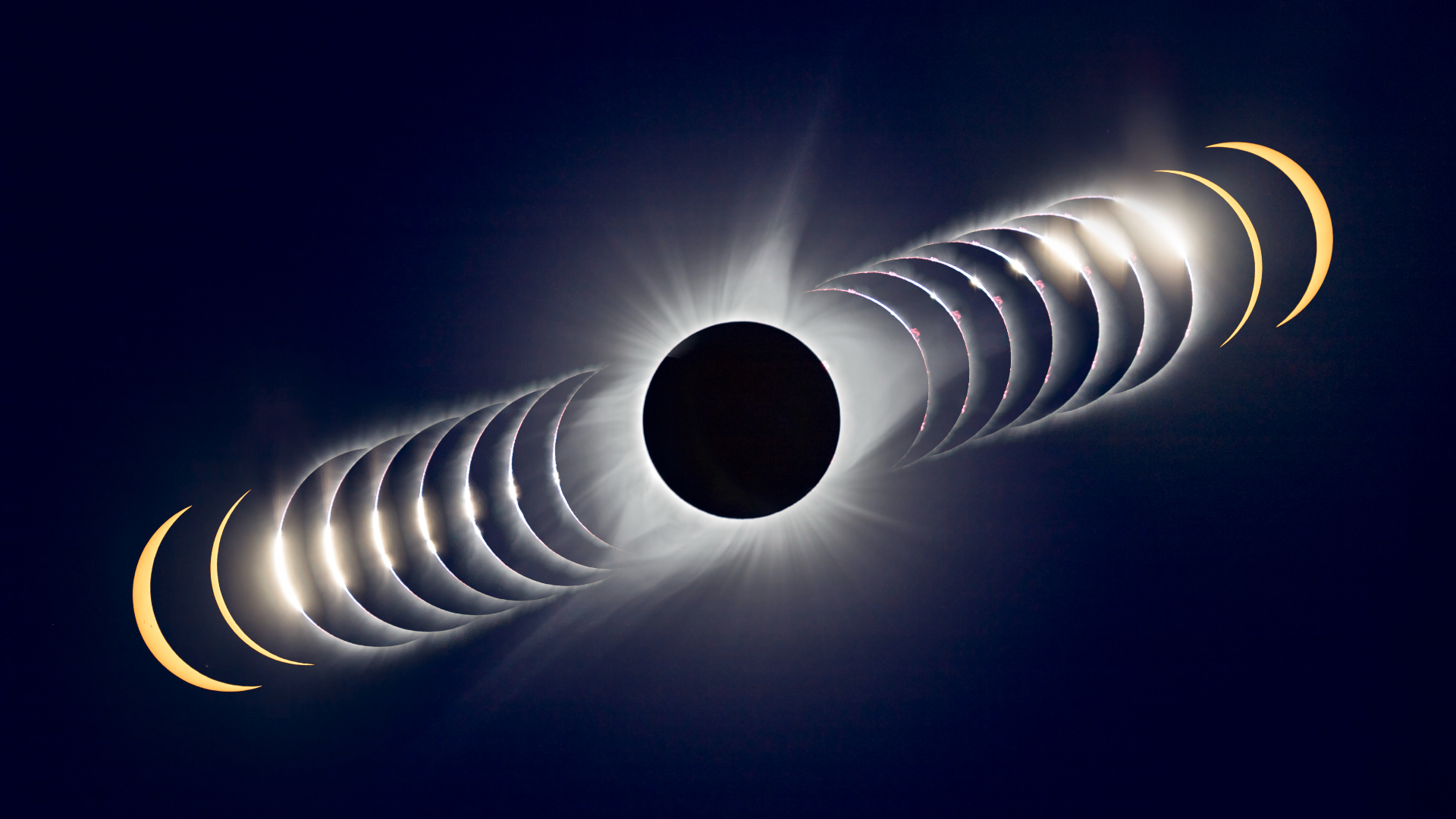

This event is associated with a total eclipse, in which the moon completely blocks out the disk of the sun. During a total eclipse, we are treated to a rare view of the sun's pearly corona; a "bucket-list event." At the same time, darkness settles over the landscape allowing for some of the brighter stars and planets to be seen. Meanwhile, an eerie saffron glow skims the horizon.

In the United States, the path of totality, averaging 123 miles (198 km), runs from southwest Texas to northern New England. Cities within the totality zone include San Antonio, Austin, Dallas-Fort Worth, Little Rock, Cape Girardeau, Indianapolis, Cleveland, Erie, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, Burlington and Presque Isle. The duration of totality will vary from nearly four and a half minutes in Texas to over three and a quarter minutes in Maine. An estimated 32 million people live inside of the totality path and countless millions more are anticipated to travel into the path in the days leading up to "E-Day."

Related: When is the next solar eclipse?

But the all-important question is: "What are the chances of clear skies for viewing the total solar eclipse?" Because the moon's shadow will sweep through a great range of geographical latitudes, from seven degrees south to 49 degrees north, the weather prospects along the path will vary markedly.

And unlike the last U.S. total eclipse in 2017, which occurred during the generally favorable weather month of August, the tempestuous month of April is a whole different story.

NEVER look at the sun with binoculars, a telescope or your unaided eye without special protection. Astrophotographers and astronomers use special filters to safely observe the sun during solar eclipses or other sun phenomena. Here's our guide on how to observe the sun safely.

Stormy times of April

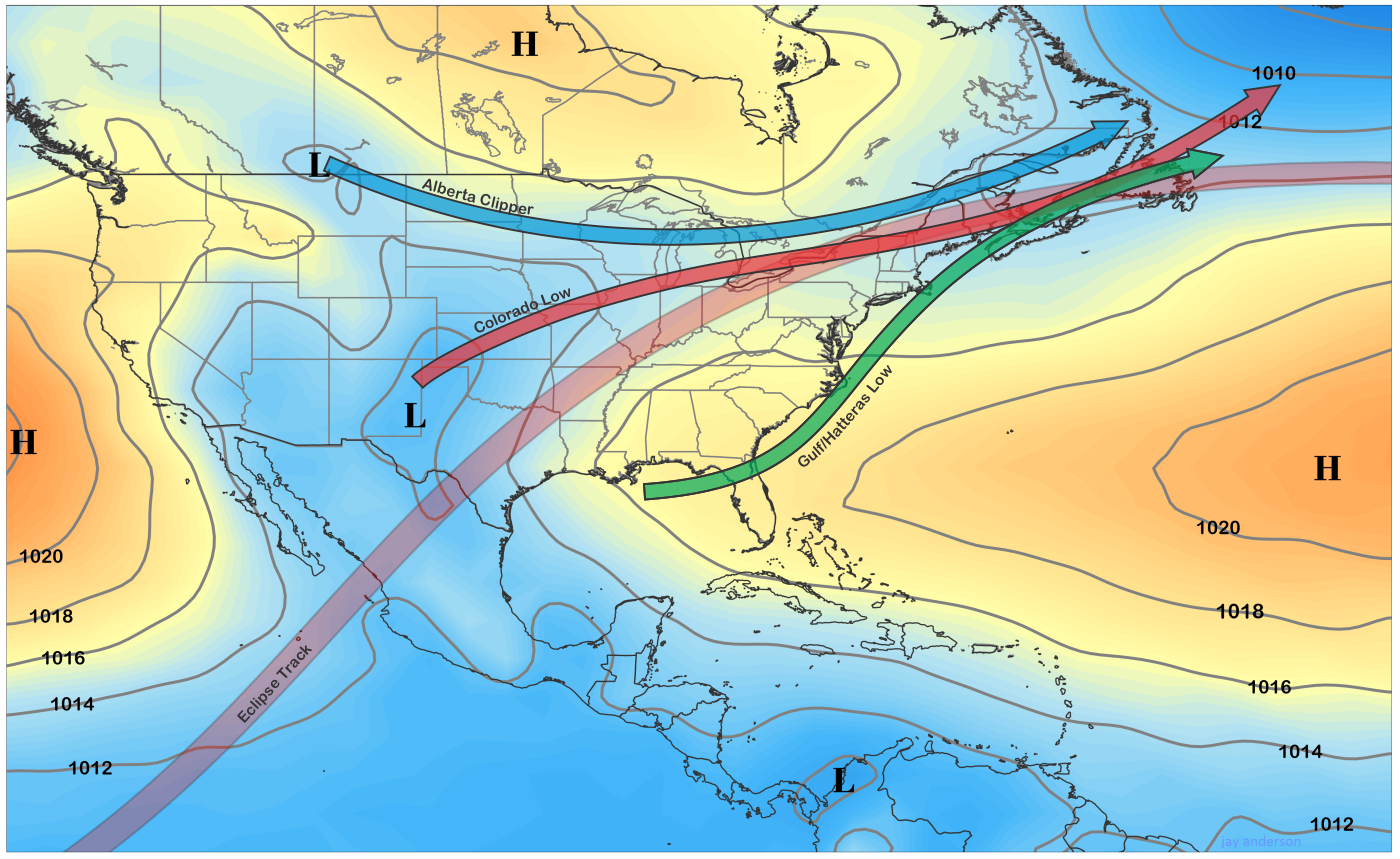

"April is the month with the greatest number of storms," according to weather historian David M. Ludlum (1910-1997), in a report published in The Country Journal New England Weather Book" (Country Journal Publishing .pg18) in 1976. It is easy to understand why by examining the diagram above, kindly provided by Canadian meteorologist, Jay Anderson of eclipsophile.com.

During April there are not one, but three active storm tracks that adversely influence the weather across the United States: The Alberta Clipper, the Colorado Low and the Gulf/Hatteras Low. What is pictured in the graphic (along with the totality path) are the "mean" positions of each storm track, as there can be some variability. As Anderson notes, "These storms are large systems with extensive cloud shields that can almost entirely obscure the U.S. and Canadian portions of the track if one happens to lie in the wrong position on eclipse day."

Probably the most active of the three is the one from the Gulf of Mexico northward along the Atlantic Seaboard, which includes a cyclogenetic area off the Outer Banks of North Carolina, where new storm centers are created and others regenerated, creating powerful nor'easters for New England and Atlantic Canada. The Alberta Clipper and Colorado Low are also significant weather-makers in their own right, sweeping across the Great Lakes and Midwest, ultimately on trajectories taking them toward the Saint Lawrence Valley; their trailing frontal systems regularly sweep across the Plains states, Tennessee and Ohio River Valleys and points east, bringing alternating wind shifts as well as clouds and precipitation.

Climate clues

To try to get a good idea as to where along the totality path will provide the best options for clear skies, we need to utilize climatology, only because there is no reliable alternative. A meteorological weather forecast for eclipse day is not possible more than a week or so ahead of time. For mid-latitudes during late winter and early spring, large daily deviations from normal frequently occur. And we must also take into account the eclipse itself, for even if April 8 starts off with exactly normal cloud cover, it would not be normal at the time of totality because of the roughly 75-minute interval of increasing partial eclipse. During that interval, the reduced solar heating will result in a cooling of the local atmosphere, attended by decreased cumuliform clouds as well as an increase of stratiform cloudiness, as has actually been observed at past eclipses.

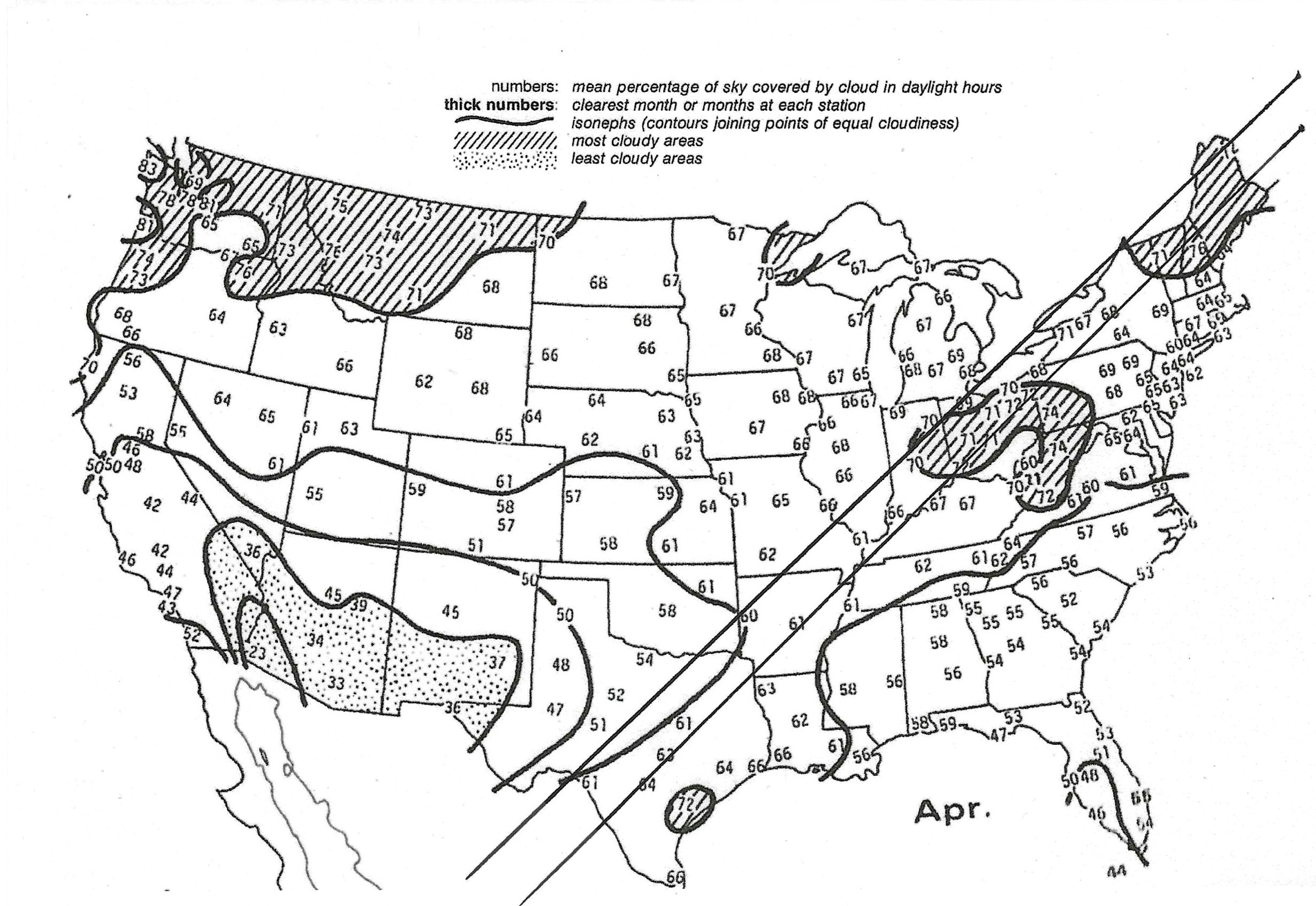

Presented in the figure above is a map depicting cloudiness near and along the path of totality taken from the book "The Astronomical Companion" by Guy Ottewell. The map is based on long-term (30-year) information from the National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, North Carolina. The totality path of the April 8 eclipse has been added. The numbers refer to the mean percentage of sky covered by cloud in daylight hours; smaller numbers mean a clearer sky. Thick numbers refer to the clearest month of the year (in April, confined to Florida). Thick lines are isonephs, contours joining points of equal cloudiness.

Cloudiness in the middle latitudes generally increases poleward, because at lower temperatures less water vapor is needed for saturation and condensation.

Hatched lines delineate the areas with the greatest amount of cloudiness. Unfortunately, there are two such areas found along the totality track: one over the Ohio Valley into western Pennsylvania and another across northeastern New York and northern New England. Somewhat less cloudiness is found farther south over Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas, but it's only a modest drop off of roughly 10 percent.

Augmenting the cloud map, I prepared the table below using NOAA Local Climatological Data, and provides for 16 selected stations the average number of April days (sunrise to sunset) that are clear to partly cloudy, Cl-Pc (0.0 to 0.7 cloud cover); cloudy, Cd (0.8 cloud cover to complete overcast); rainy, R (0.01 inch or more of precipitation); percentage of cloud cover, CC, and percentage of sunshine, SS. Stations listed with an asterisk (*) are outside the path of totality.

The apparent inconsistencies between sunshine percentage and percentage of cloud cover figures arise because thin cirriform clouds are included in the cloud cover data. The sun often shines through these with sufficient intensity to activate a sunshine recorder. The sunshine data gives too optimistic an estimate of the probability of seeing the eclipse, while the cloud cover data are too pessimistic. Of course, even a slight layer of cirrus cloudiness would interfere with viewing the outermost parts of the corona, and yet a considerable amount of detail can still be seen through a layer of thin cirrus or perhaps even a layer of thin cirrostratus.

Thus, the true chance of seeing the eclipse to some degree probably lies somewhere between the probabilities inferred from the two value sets under the CC and SS columns.

Let's make this perfectly clear . . .

On the other hand, a professional astronomer whose success depends on a pristine clear sky, will need to rely on a more stringent set of probabilities; what are the chances of seeing the eclipse in a perfectly clear, blue sky? As we have seen, April weather is extremely variable and changeable, so that any location there is some hope of very clear skies on eclipse day.

In the table below are percentages for the same 16 stations. It is the average of two items: 1) The percentage of clear sky (0 to 3 tenths overcast) plus half the percentage of a partly cloudy sky. (4 to 7 tenths); 2) 100 minus the average percentage of total cloudiness.

As you can see, from Texas through Arkansas, the odds for a clear sky on eclipse day is a little less than 50-50. By the time the moon's shadow reaches northern New York and New England, the odds are only a little better than 1 in 3.

Severe weather

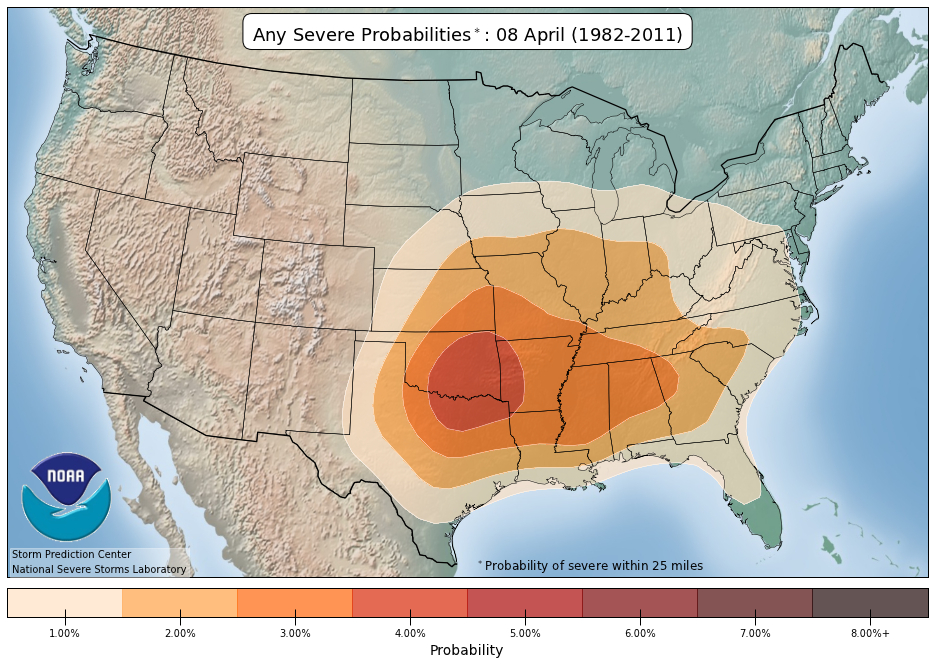

Yet another concern is the formation of possible thunderstorms, perhaps accompanied by potentially damaging winds and even perhaps a tornado. Such activity tends to "boil-up" during the mid-to-late afternoon hours, although depending on local atmospheric conditions, a storm could "pop" at almost any time of the day. On average across Dallas-Fort Worth and Little Rock, there are an average of six or seven days in April when thunderstorms occur. This drops off to about three at Erie, PA. The figure below, kindly provided by Keli Pirtle of NOAA's Storm Prediction Center, shows the probabilities of severe weather on April 8. The greatest threat — if it were to occur at all — unfortunately encompasses that part of the totality path that crosses northeast Texas, southeast Oklahoma and western Arkansas.

Mexico and Canada

Unlike in 2017, when totality was confined to the United States, in 2024 we will share totality with our neighbors to the south (Mexico) and to the north (Canada). Here are a few words regarding eclipse weather for these two countries:

Mexico is where totality will last the longest (4 minutes 28.3 minutes, near the town of Nazas) and where the sun will appear highest (nearly 70 degrees) in the sky. April is the final month of the dry season in Mexico and from a climatological standpoint, prospective weather conditions compared to the U.S. are extremely promising. Cloud cover along the totality path from Mazatlan to Monclova averages only 20 to 30 percent. This increases as one heads to the northeast, reaching 45 percent at Piedras Negras at the Texas border.

In Canada, the totality path crosses southern portions of Ontario, Quebec (including Canada's largest city, Montreal) and then slices through the Maritime Provinces before heading out to sea. Climatologically, the viewing odds are rather similar to New England. But those located in Ontario near and along the shores of Lake Erie (from Leamington to Weiland) and Lake Ontario (from Brighton to Kingston) might benefit somewhat from a view of the sun toward the south-southwest across a long stretch of water, which would avoid the development of possible afternoon cumulus clouds. The same may also hold true for southwest Newfoundland (Stephenville to Codroy; Port aux Basques to Burgeo), looking out across the Cabot Strait.

Statistics: Danger!

In his 1973 novel, Time Enough for Love, science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein came up with the following aphorism: "Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get!"

How true this is! One should always remember that all of the climatological statistics that have been noted here are not absolute. Indeed, it has certainly happened that avid eclipse watchers have in the past ventured to a location that climatology indicated would be a favorable place to watch an eclipse, but in the end came away disappointed when clouds prevailed instead.

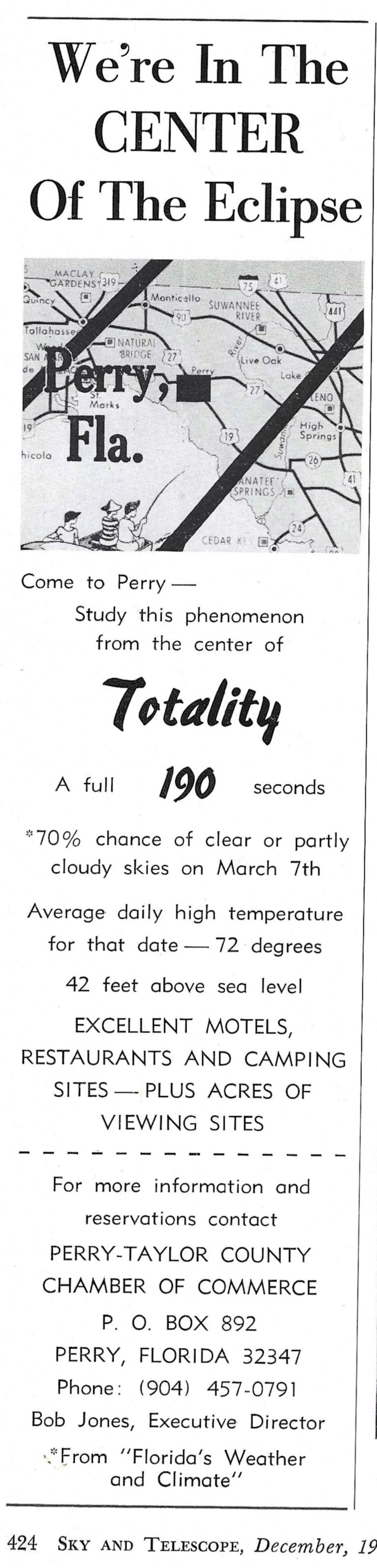

An excellent example of this is a saros predecessor of the upcoming eclipse, that of March 7, 1970. In the December 1969 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine, the Chamber of Commerce of Perry, Florida placed an ad, boasting that they were in the center of the total eclipse path and would see 190 seconds of totality. Additionally, the ad pointed out that there was a "70% chance of clear or partly cloudy skies on March 7th." As a result, thousands gravitated to Perry, assuming that fair skies were a given for that part of the eclipse track.

Unfortunately, a low-pressure system developed over the Gulf of Mexico and spread a solid overcast over much of the southeastern U.S. on eclipse day.

In view of such weather uncertainties, plans about where to observe should be kept flexible up to the latest possible time before the eclipse, which (as was the case in 2017) occurs on a Monday. Starting the week before, NOAA's Weather Prediction Center will provide increasingly reliable forecast products, which will enable people to choose a location where the chances of a cloudy sky are low. These can be augmented by forecasts issued by National Weather Service forecast offices located near and along the totality path. On the weekend before, the very latest meteorological data, including scrutiny of satellite images and radar scans should be used to modify the plans based on climatological data only.

Conclusions

By far, the best weather conditions favor the aforementioned regions of Mexico. In early April, the percentage of cloud cover prevalent in this area is chiefly in the 20's, and the chances of an April day with less than one-third of the sky covered by clouds are about two in three. The probability of seeing the sun at any given time on April 8 is better than 75 percent. These are considered very favorable prospects for viewing the eclipse.

In contrast to these conditions, the weather outlook from Texas through the Deep South look marginal, and going from the Ohio Valley and points north, downright unfavorable. Climatological records indicate little difference, from the point of view of weather from Texas to Arkansas. Throughout this area, average cloud cover in April is consistently about 60 to 65 percent; clear days occur on April 8 in about 45 to 50 percent of the years for which records are available, and the chances of seeing the eclipsed sun at any given moment on April 8 is about 55 to 65 percent in those areas from Texas to Indiana where the total eclipse will occur. These conditions are somewhat better than those for the Northeast U.S., Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada, but, surprisingly, not that much better.

Regardless of where you plan to be, staying mobile to dodge cloud cover will always enhance your chances.

To those who plan to position themselves in the totality path with hopes of experiencing the phenomena that accompany that magical exclamation "totality!" we wish one and all good luck and clear skies.

Joe Rao was a broadcast meteorologist for over 40 years and holds the Seals of Approval of the American Meteorological Society (AMS) and National Weather Association (NWA). He also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.