Each summer Sports Illustrated revisits, remembers and rethinks some of the biggest names and most important stories of our sporting past. Come back all week for more WHERE ARE THEY NOW? stories. This story first appeared in the print version of Victory Journal.

Gary Smith boarded the first train out of Rome and took it to the end of the line. He crossed the street right as a bus pulled up and rode it to the end of the line too. Now, a little red car slid to a stop beside his outstretched thumb and a man with wild black hair and wild black eyes beckoned him to get in.

It was a linguistic scramble as the man attempted to engage Smith. Italian, then English, and finally a slapdash mess of Spanish and French to get to the most pressing matter: “Where to?”

“Wherever you’re going,” Smith responded. And so, the man turned the key and they set off, the Talking Heads’ “Psycho Killer” playing on repeat. Eventually, they pulled into a tiny village, Castel Viscardo, on the calf of Italy’s boot, 4,200 miles and a universe from the Midtown Manhattan Sports Illustrated office. It was late summer, 1983.

Gary Smith stayed in town that night, and then for months thereafter, working at the brickyard and picking the region’s famous grapes. He’d be back again with his wife and then three more times with children in tow. The magazine had paid his way across the Atlantic, but the train ride and the bus ride and the months abroad had been for only him. None of it made the story. It was never meant to.

Illustration by Felipe Flores

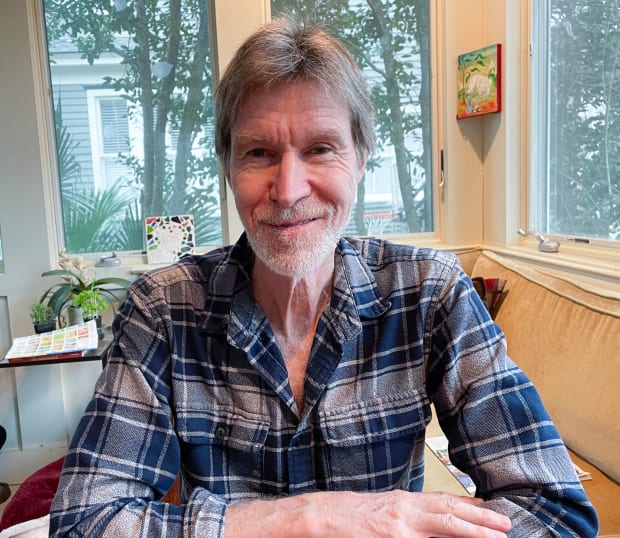

Two years ago, a friend from Charleston mentioned a coworker who taught mindfulness to elementary school students. A few years in, someone finally asked that friend, “You know who that is, right?” It was the sportswriter Gary Smith.

The image of Smith, winner of a record four National Magazine Awards, living anonymously, was perfectly antithetical to that of a grizzled sportswriter telling war stories from a barstool. The unassuming legend with an unobtrusive name had seemingly disappeared into an afterlife on the Carolina coast.

Ben Yagoda once wrote on Slate: “Gary Smith is not only the best sportswriter in America, he’s the best magazine writer in America. The only injustice is that, outside the small world of editors who vote for the National Magazine Awards and the even smaller subset of Sports Illustrated readers who pay attention to bylines, he is a nobody.”

Smith existed apart from Sports Illustrated, even when his writing was definitional for the magazine. He looked like a member of “John Denver’s backup band,” to use SI writer Steve Rushin’s framing, and always lived far from New York City, in Charleston for decades, with time in Bolivia, Australia and Spain peppered in between. He wrote just four stories a year for three decades, each a sprawling excavation of a sports figure’s soul. Even then, during the magazine’s flush times, he was an anomaly.

Last spring, I stood in front of a packed café in Charleston’s French Quarter. Smith, a lithe 68-year-old, rode up a few minutes late, waving and apologizing from the seat of a black beach cruiser. He wore a cerulean T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. His smile cast lines around his bright blue eyes and his thin beard was white, but he looked boyish.

It took a moment to find a lunch option for Smith, who struggles with spicy foods and is vegetarian. As we ate, our conversation bounced from his first newspaper job, to Al Davis’s coaching career, to Smith’s rock band, Post-Life Crisis. When it jumped to the precarious state of sports journalism, Smith leaned back in his chair. “This sounds like it’s gonna be a mournful story,” he said, grinning. “The asteroid came and there’s one dinosaur left and he’s out in Charleston.”

Illustration by Felipe Flores

Read More Where Are They Now? Stories

As Smith and I spoke again and again this spring, the conversation would inevitably return to: “Why retire?” From unstable footing, it’s easy to perseverate on the decision to leave solid ground. Journalists are not objectivity machines; we see the subject through our own scratched filter. But to try to place Smith in the world of anxiety and striving of the modern journalist is a folly.

Smith existed outside the journalism industry while working within it, resisting offers from other magazines and lucrative book and TV deals. It was his rare gift—that clear-eyed view of what life could be and where work should fit in—that separated him.

In David Halberstam’s book on the Vietnam war, The Best and the Brightest, he wrote of his apprehension in taking on the years-long book project: “A journalist always wonders: If my byline disappears, have I disappeared as well?” Smith smiled and closed his eyes as he listened to the quote. “You pour yourself into the writing, but it is not yourself,” he says, after a pause. “If you let it get that sticky, you’re stuck.”

Gary Smith started his career in journalism while he was still in high school. His older sister Sue (Gary is the fourth of nine Smith kids) had won the Delaware Junior Miss pageant and sat on the judging panel the next year alongside the sports editor at the Wilmington News-Journal. While there, Smith’s mother asked for advice for her sports-obsessed 16-year-old son and the editor said he should come by the paper the next day. Smith got a job, taking on menial tasks like tracking down local high school scores and typesetting horse race results. In college, while Smith was completing his English degree at La Salle, the Wilmington assistant sports editor moved to the Philadelphia Daily News and hired him full time. Smith went to class and then to the newsroom, where he worked nights and weekends.

After seven years at the newspaper, he was contacted by an editor at Inside Sports, Newsweek’s experiment in literary sports journalism. Smith wrote a few freelance pieces for the magazine and then was hired on as the only staff writer.

The magazine folded after three years, and it was then, in 1982, that SI reached out, offering a coveted staff writing position. Smith, just 28 years old, responded with a counter offer: He would take half the money to be on contract to write four feature stories per year. “I was just feeling like a student of life at that point. There’s so much I want to see and learn that if I’m on the wheel with deadlines I just won’t be able to experience,” he says. “It partly has to do with my personality type that I was pulled to do four pieces a year. I was fine without the champagne of a byline.”

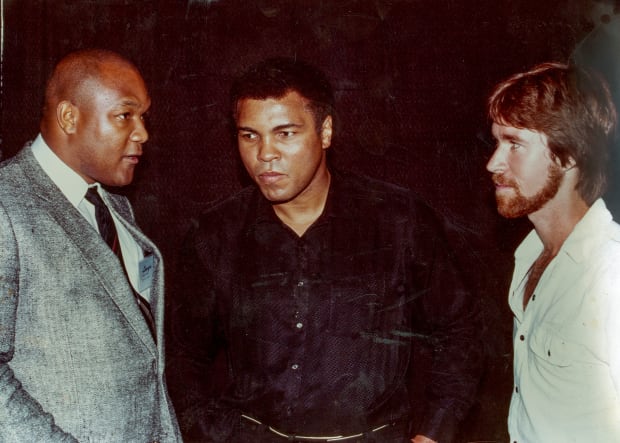

Courtesy of Gary Smith

In 1987, Smith was diagnosed with melanoma. The plastic surgeon Duke Hagerty removed the cancer and the two have met weekly since ’91, discussing books they read concurrently, reading passages aloud and diving deep into “how the ideas in them play out in our personal lives, our culture and the species.” The literature often pointed toward the meditative process, “slipping in between the seams.” So, when he turned 50, Smith started doing yoga and, not long after, went on his first 10-day meditation retreat. The time Smith had negotiated for back in 1982 had freed the space to explore the world and himself. It also allowed him to take months on each profile.

So, he wrote under that contract for eight years until the realities of adulthood—a wife and kids and a mortgage—made healthcare and benefits a necessity. By that point, he’d built up enough capital—penning seminal profiles of Mike Tyson and Muhammad Ali, as well as portraits of Soviet pole-vaulters and eccentric aces—to come on staff at the higher rate while continuing the four-stories-per-year structure. It was 1990. Gary Smith had the best job in sports journalism.

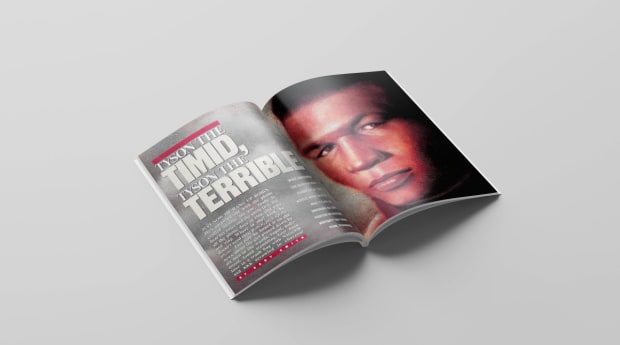

At the time, Rick Reilly was the more boisterous star of the magazine. The grenade-lobbing writer USA Today called “the closest thing sportswriting ever had to a rock star” once appeared in a Miller Lite ad alongside Rebecca Romijn. Smith was more like sportswriting’s Townes van Zandt. SI contemporaries dubbed the soft-spoken Smith “the demon beat writer” for his uncanny ability to uncover each subject’s hidden demons. The sportswriter who read Hermann Hesse was unparalleled in his ability to find a superstar’s subterranean psychic influences. His Tyson profile charted the path from a traumatic childhood to the heavyweight belt; his Andre Agassi story traced the tennis player’s obsessive rebellion back to an overbearing father.

Courtesy of Gary Smith

Reilly and Smith had an unlikely friendship—“sort of mismatched socks,” as Rushin puts it—and were inseparable while covering the Olympics or on the SI retreats, dancing, drinking and singing karaoke. To Reilly, who eventually took a lucrative deal to move to ESPN in 2008, it was fascinating to see how Smith leveraged his industry capital into more freedom, rather than more money. “A lot of people would have probably been like, ‘Screw that. You guys love me. You need me. I’ll write more, but you’ve got to triple my salary,’ ” Reilly says. “But no, he wants less work. You know, ‘I’ll do the same salary, but a lot less work. So that I can pour myself even deeper into these people.’”

Part of the Gary Smith story is, of course, inextricably tied to the story of SI. Smith admits he “caught the sweetest wave in the history of longform journalism.” He was well compensated, and his magazine mattered in a way that gave him the power to request access that feels alien these days. Tyson, Woods and Agassi were the biggest names in the sports world, and they opened their lives to Smith—allowed the man Reilly describes as “Columbo, only skinnier” to peer in and search for the buried root of it all. The athletes agreed to let that light be shined on their darkest parts because the illumination itself held value.

“The trade was: ‘You'll explore some of my shadows in this piece, but out of it, I'll get this coverage in a national forum that can be beneficial for my career or what I want to do after,’” Smith says. As the magazine industry shrunk and the athlete’s pulpit grew, the calculus inverted. The magazine needs the athlete now, not the other way around. “So, the shadows get shut down and the person controls the whole thing. It’s a step of trust no longer necessary for celebrities to take. So why take it?”

That now-legendary Tyson profile contains a revelatory scene: At one point, the heavyweight champ longingly reminisces about robbing strangers to the actress Robin Givens as they ride through Brownsville, Brooklyn, in a silver Lincoln stretch limousine. “Being profiled by Gary Smith would be like being paraded down Main Street naked in a cage. Everyone sees everything you are, warts and beauty,” Reilly says. “And you couldn’t really complain about it, because he usually got you so right.”

But Reilly’s framing distorts Smith’s actual approach—the profiles are less parade than portraiture. As his SI colleague S.L. Price wrote when Smith retired in 2014: “Smith had little interest in painting Mike Tyson or Allen Iverson as pure villains or Dean Smith as a pure hero. He knew better. His great achievement was an inversion of sport’s central allure—the way it reduces messy existence to clear winners and losers, good guys and bad guys.”

Because Smith was obsessed with excavation, not exposure. “Judgment just closes off so many possibilities and doors and windows. So, the more you open to what created the human in any given moment, the richer the terrain you as a writer have to explore,” Smith says. “It’s in the ambiguities, the paradoxes of human beings, where truth lies.”

Smith used the lyrical fluidity of sports writing to explore humanity. And he chose to turn that magnifying glass inward just as often.

The SI newsroom at 1271 Avenue of the Americas was the big leagues of sports media. Every week, journalists and photographers would file from every corner of the sports world, and more than 3 million 120-page glossy behemoths would land at newsstands and front doors.

The bullpen, the cluster of offices where the fact checkers sat, overflowed with young reporters dreaming of bylines in the feature well. A bloated story from an old hand would elicit eyerolls; a masterly piece was a reminder that most writers never reach that peak. And yet, every three months, when the first draft of the new Gary Smith feature arrived on the ancient Atex computer system, the entire office would go silent. “Word would go around that Gary’s story has landed,” Rushin says. “Everybody would get on their Atex terminals and read it and then gather in the hallway to kind of marvel.”

Courtesy of Gary Smith

For Smith, there was never pressure to chase clicks or move the salacious stuff to the lede. There were ESPN offers, sure, but he valued the space and time afforded by his SI gig. There were inquiries about book deals after the publication of “The Ride of Their Lives,” “Damned Yankee,” “Someone to Lean On” (which would eventually become the movie Radio), and many others, but he’d already spent months pulling back the layers of his subjects. “To then spend a year pumping air back into it and making it a 300-page book, it felt like there wouldn’t be as much creative spark,” Smith says. “I just want to be learning and following a thread that feels like it’s alive and growing. The philosophical-slash-psychological part of this was something that fascinated me from early on.”

As I spoke to Smith and to his contemporaries, I felt myself searching desperately for Smith’s own demon within—the unseen bit of Gary Smith that had spurred him from the best job in the industry. When I asked Reilly, he said I was chasing a ghost. “We all were supposed to constantly hunger to get bigger and richer and more famous. He never had it,” Reilly says. “I was not surprised at all that he just kind of hung a Do Not Disturb sign on his life and started teaching people to be Zen and playing guitar and traveling.”

Smith had spent 32 years at SI dissecting coaches and athletes, but also the society that surrounded them. His best profiles of lesser figures were stories about how sports muddied moral codes—in a profile of Notre Dame coach George O’Leary, he asked: How should we weigh a coach’s legacy against his lie? In a profile of high school basketball star Richie Parker, he showed how a sexual assault can destroy everything it touches.

His profiles of superstars were often something else: stories of man versus machine. In his Andre Agassi feature, Smith shows us a tennis star whose image brought him everything but happiness—even Agassi’s attempts at rebellion were co-opted and sold. The profile traces the desperate search to replace image with meaning.

Though he eschewed it, image served Smith’s career as well. Not with riches or fame, like Agassi or even Reilly, but with space and with power. The image of the seeker—the Zen master a million miles from Midtown—helped bind him to the perch from which he could seek. “The worst thing that you can do as a writer at SI is actually come into the offices and meet the editors and become a real person,” former SI writer John Walters says, “You lose your aura.” But editors’ pencils got lighter on a Gary Smith draft, and word count was never questioned.

Rushin says that when Smith retired, he pictured two versions of his SI afterlife: that Smith would disappear like Johnny Carson, or that he’d publish a 1,000-page masterpiece of a novel. “My guess was that it’s hard to write The White Album every year,” Walters says. “Like, Gary just couldn’t go and cover the Tampa Bay Lightning.”

But Smith says the calculus was simpler. “To find stories where I felt like I could learn something and wouldn’t be repeating on a subject, that grew more challenging in the latter years,” he says. “There was a bit of a sense of not having as much desire to go and fill all those notebooks. It wasn’t as fervent a desire as the one that had been compelling me all the way up until that moment.” It was time to walk away.

Smith tells me he’s writing a novel: a heavily researched, imagined history of Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. It’s been seven years and he’s still not certain when it’ll be done. But he’s sure it won’t be long now. For decades, he’d had three months per story; now he spends four hours every day basking in the novel’s world. “I don’t feel any need of a deadline to get me to produce something. I’d rather just work it until it gets better,” he says. “The process is really what I love. The doing of it, not having it done.”

“Imagine it? Four hours every day, and you’re not anxious about when it’s gonna come out?” Reilly says through a laugh. “His life really is very Zen. He’s doing that and enjoying that. Then he makes lunch and he loves doing that. Then he does the dishes, and he likes feeling the water and soap on his hands. He’s just in the moment. It’s a wonderful thing.”

Read Gary Smith’s “Tyson the Timid, Tyson the Terrible”

So, perhaps that was the secret all along. It’s what let him live for months in Italy a year into the SI gig others would die for. It’s what let him stay put for three decades instead of chasing greener grass. It’s also what let him walk away. Today, the most decorated sportswriter of his generation spends time teaching students at Title 1 schools mindfulness as a tool to be attentive and calm their nerves. He rarely shares a Tyson or Tiger Woods anecdote. Imagine it? “It’s an incredibly complicated thing that we’re thrust into as human beings. You can either take it at face value and just scramble or survive, or you can try to understand as best you can what’s really happening here, inside of us, around us,” Smith says. His years of reading, writing and exploring were in the service of a goal: “To learn how to play this game most wisely, with the least amount of suffering and the most amount of enjoyment.”

Other writers speak of Smith’s ability to disappear, to be absent and allow the subject to be fully realized on the page. And yet, when I asked, Smith admitted there is a bit of a ghost memoir in an oeuvre like the one he left at SI. How could you write millions of words and not reveal yourself as well? Smith spent a life on the edge of the limelight, remaining mostly invisible. But he’s right there in each of his stories; you can find him on the edge of the frame if you squint.

In his prescient profile of a 20-year-old Tiger Woods, Smith asks the question: “Who will win? The machine . . . or the youth who has just entered its maw?” He tells the story of a child built to be the greatest, but more than that—built to be a historical figure of change, like Gandhi with a 9-iron.

After a section on the strange brew of Buddhism and Green Beret training that unleashed Tiger’s superhuman focus, Smith writes:

“To hell with the Tao. The machine will win, it has to win, because it makes everything happen before a man knows it. Before he knows it, a veil descends over his eyes when another stranger approaches. Before he knows it, he’s living in a walled community with an electronic gate and a security guard, where the children trick-or-treat in golf carts, a place like the one Tiger just moved into in Orlando to preserve some scrap of sanity. Each day there, even with all the best intentions, how can he help but be a little more removed from the world he’s supposed to change, and from his truest self?”

It’s telling that this is the Tiger that Smith saw. For a man engrossed by the distorting effects of fame on the superstar athlete, should we really be surprised he made the choices that he did?

It wasn’t Smith who first shared the Castel Viscardo story. It was Reilly. He brought it up, still a bit awestruck by his friend after all these years. “He just wants to explore the world until there’s no inch left,” he says. “When he explores it all, he says, ‘Wait a minute, there’s about eight inches between my ears. Let’s see what that’s like.’ Now he explores that too.”

When I ask Smith about the trip, he corrects an error in Reilly’s retelling: He’d been in Rome, not Madrid. Then he’s off, telling me about the hand gestures at the crowded bar and how they baked bricks the old-fashioned way in the afternoon sun. He’d been in Europe on assignment, profiling an Italian long-distance swimmer ahead of the 1984 Olympic Games. The interviews were done, so he headed to the station to ride the first train and then the first bus to the end of the line. “When I got to the end of the line, I got off and put my thumb out,” he says. “Whoever picked me up, wherever they were going, that was where I was gonna land. And, you know, just see what happened.”