The term ‘progressive’ has come to denote – at least in the minds of the unthinking mainstream critics and consumers – a genre or style, something to do with sparkly capes and impenetrable lyrics about wizards. Actually, most bands are progressive in their way, trying to move their music forward. It’s just that they don’t get the label because they don’t sound like King Crimson in 1969.

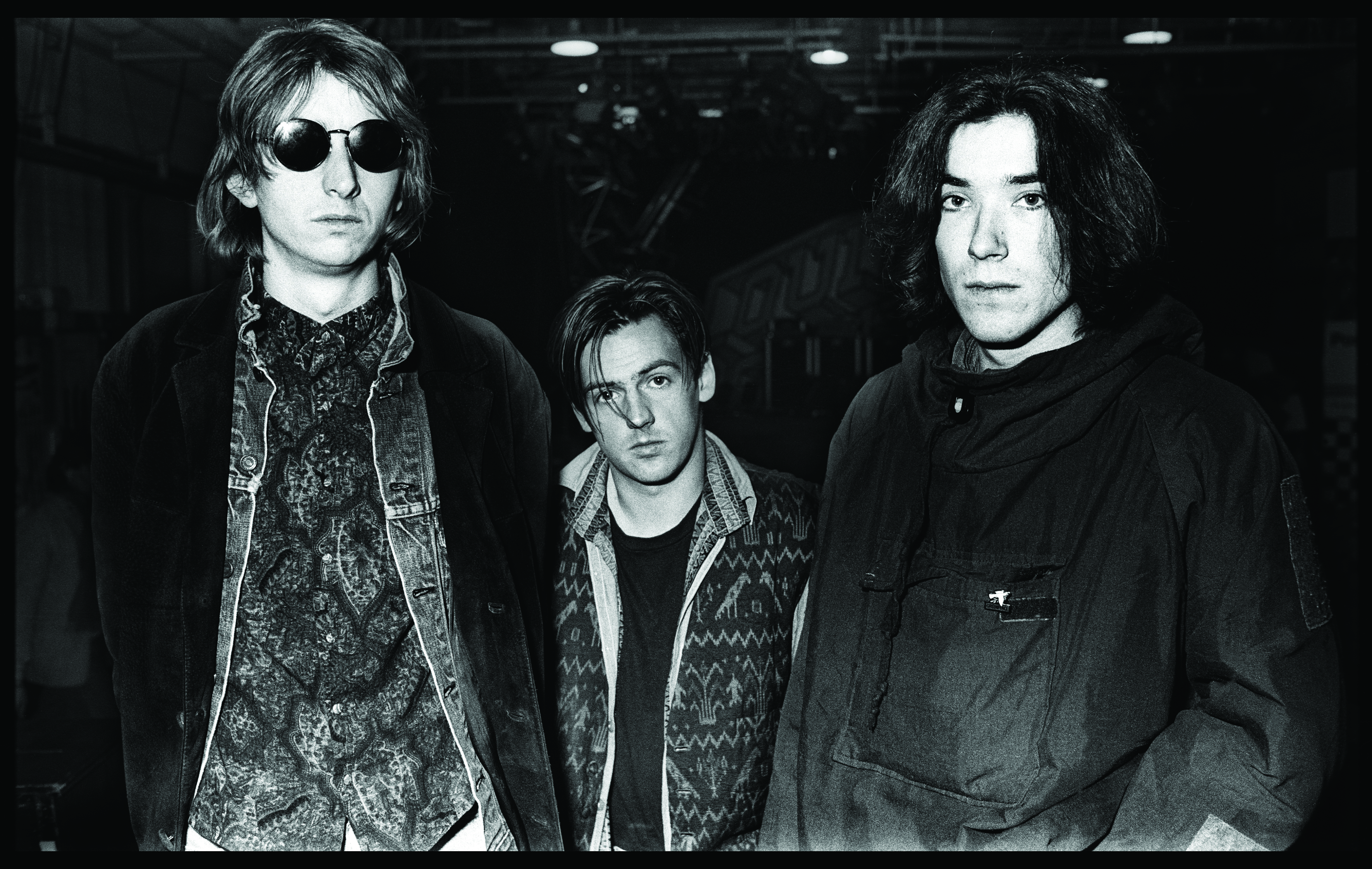

Talk Talk are a prime example of a band who progressed, a band who made a great leap forward and changed everything.

In interviews, Talk Talk frontman Mark Hollis always spoke about Miles Davis and Bela Bartok, though it was hard to square his professed influences with the happy clappy synth pop that his band made. Songs like My Foolish Friend and It’s My Life were beautifully crafted pop artefacts, but nobody at the time saw Talk Talk as anything other than the band you got into while Duran Duran were on a hiatus.

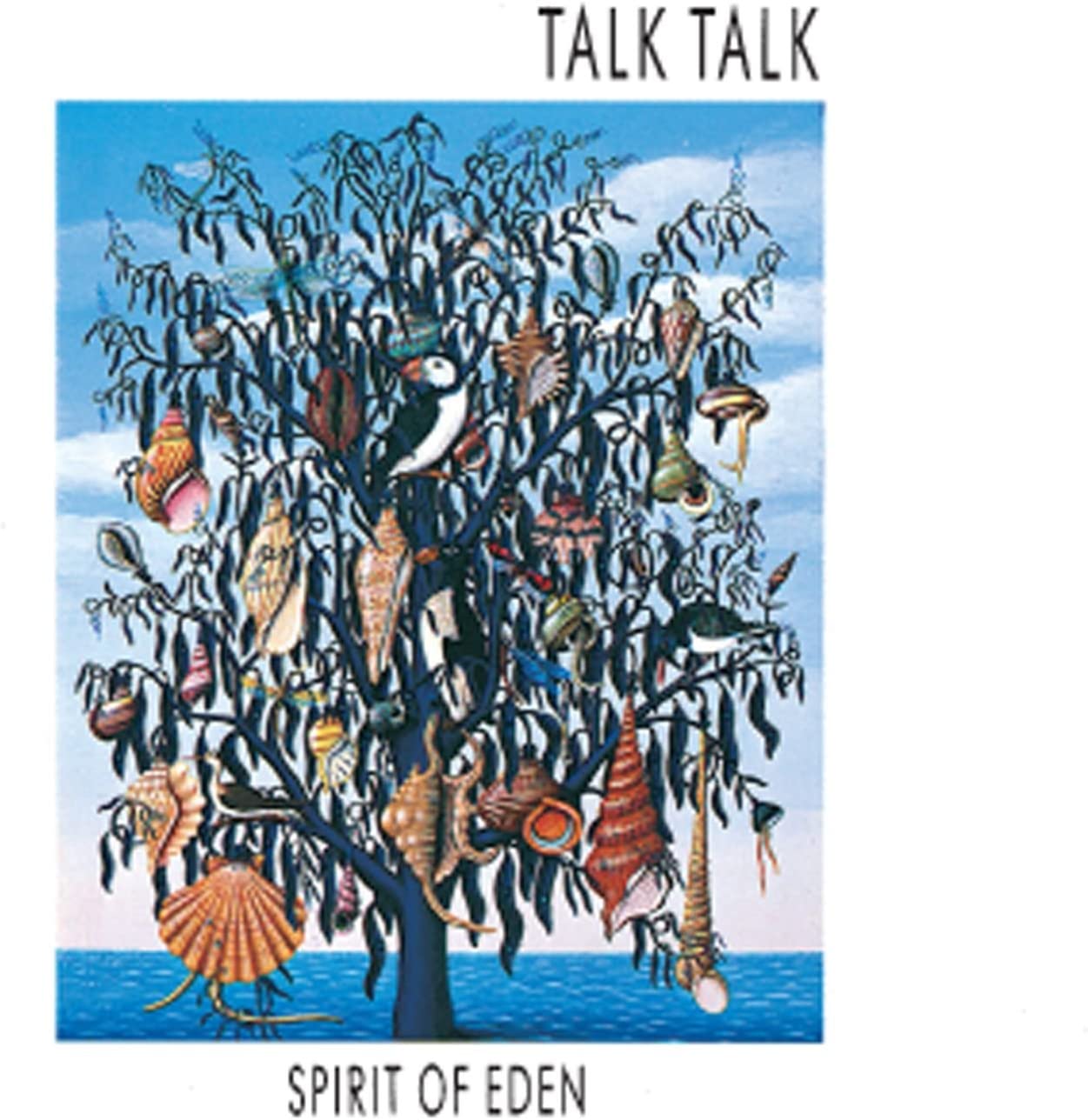

Talk Talk were successful; Smash Hits and Top Of The Pops mainstays. Along with Culture Club, Tears For Fears and A Flock Of Seagulls, they were part of a second British invasion of the US. Their big hit, 1986’s Life’s What You Make It, and the album The Colour Of Spring showed a new maturity as well as sustained Top 10 status. Their parent label EMI gave them carte blanche to record the follow-up: unlimited time and money with minimal interference. The result after a year in the studio was Spirit Of Eden, a monumental work whose iconic status continues to grow. Constructed from hours of improvisations – sometimes they played in complete darkness to get the mood right – and edited by Hollis and producer Tim Friese-Greene, Spirit Of Eden bears little resemblance to the band’s pop incarnation. Plaintive Miles Davis-like trumpet solos are layered on top of glacially slow ambient washes, Hollis’s distinctive voice being the only thing with any seeming continuity with the band’s previous sound.

On hearing a cassette of the album, EMI panicked as executives saw their fat bonus cheques evaporate. They asked Hollis to replace some songs and rerecord others. He refused.

The album sold poorly, partly because of the challenging nature of the material, but also because the band didn’t tour in support of it. It was, Hollis, admitted, impossible to play live.

In retrospect Spirit Of Eden and its almost-as-good follow-up Laughing Stock started a sea change in music, along with US rockers Slint, paving the way for a new post-rock underground movement that includes the more experimental side of Radiohead as well as Chicago-school bands like Tortoise.

Hollis, after one brilliant solo album, retired from music, and lived life away from the spotlight up until his death in 2019. His legacy lives on through Spirit..., though. Now regarded as a classic, it just took the rest of the world a little while to catch up.

The original version of this article appeared in issue 1 of Prog Magazine in 2009.