{kiosq_button:center}

Almost exactly a year ago my colleague, Josh Ross, broke what became our biggest story of the year: PFC bans are set to change the face of all waterproof garments. If you haven’t already read that, I urge you to now, as it provides useful contextual information for what follows. Since that article was penned, the dust has settled somewhat and we are able to take the temperature of the industry as a whole. I’ll do my best to not rehash old information, but there may be some inevitable crossover, especially when setting the scene.

What follows is an attempt by Josh and I, primarily off the back of testing the best winter cycling jackets and the best waterproof cycling jackets respectively, to see if we can decipher which direction the future of waterproof clothing is heading. Was it right to say everything is going to change, or did we perhaps expect a greater pace of change than was reasonable from what is essentially an offshoot of the global chemical industry?

Shakedry, PFCs, and the accidental canary

I suspect, if you’re a keen cyclist (or perhaps a keen hiker or trail runner), that you’ll have come across Gore-Tex Shakedry. For many of us it represented the pinnacle of performance, right at the sweet spot where breathability, waterproof-ness, and packability intersect. And then, only a few years after its inception, Gore announced that it was set to retire the wonder fabric. In short, it wasn’t worth Gore’s while to produce; it was too costly, too time consuming, and for too small a population of users.

Had it not been retired then I suspect that nobody would have noticed the behind-the-scenes machinations going on in the industry, but as Josh found out, the retirement of Shakedry was something of an alarm call. While the impending ban mightn’t necessarily affect it, it turned the spotlight onto the industry as a whole just long enough for Josh to uncover the rumblings of industry-wide change. In short, a ban on PFCs (per-fluorinated compounds), or at least regulation heavily restricting their use, is set to upset the waterproof apple cart, particularly for Gore, which relies heavily on PFC’s for the creation of its waterproof membranes.

Impending regulation

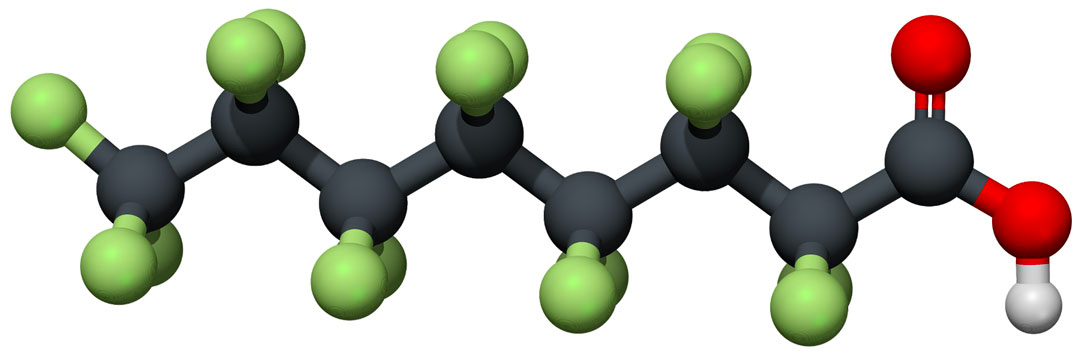

At the heart of all this is a global regulatory conversation around PFC’s, which is now an outdated catch-all term, and has been replaced by PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances). Without diving too deep into a chemistry lesson, these are, in general, nasty chemicals, often referred to as ‘forever chemicals’ thanks to the fact that they take more or less forever to break down, and as such can accumulate in the biosphere. In the same way as CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons) were banned as propellants due to the fact they devastated the ozone layer, PFAS are also either set to be, or have already begun being, much more highly regulated depending on where in the world you are.

Individual states have already begun to roll back their use, usually towards ‘essential use only’ (spoiler alert, making waterproof fabrics isn’t necessarily classed as essential). While the EU was set to enact a ban this year, lobbying from large chemical companies (according to the Guardian), has seen the proposed ban dropped.

{kiosq_button:center}

What does this mean for us cyclists then, and the wider outdoor industry? Given the worldwide reach of cycling brands, and outdoors brands generally, it seems likely that a US ban would effectively be a global ban, as brands are unlikely to want to have two different product and manufacturing streams across either side of the Atlantic, particularly if one product stream only exists because an environmental and human health facing ban didn’t land as well as was first thought; the optics of that aren’t brilliant I think we can all agree.

The US ban for now appears to be set to land in January 2025, in some states rather than federally, but in general, one way or another, the use of PFAS is going to be phased out, if not entirely then at least to limited uses only.

The problem, especially for Gore Fabrics, and any companies that rely heavily on Gore-Tex products, is that Gore’s membrane is expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, or ePTFE. The ‘F’ is the key bit here, as this means it falls under the wide-ranging umbrella of new regulations.

Gore and the PFAec quandary

Gore Fabrics (and Gore-Tex, which for the purposes of this article are synonymous) has been the name in waterproof technology for some time. The brand pioneered the use of expanded PTFE, and utilised it as a waterproof membrane in garments for practically any endeavour where water ingress is to be avoided. The manufacture of PTFE used to involve the use of PFOA, or perfluorooctanoic acid, which did the job of creating the tiny pores in the membrane, through which water vapour could escape, but through which water droplets could not pass. This is the backbone of any waterproof membrane, but if you need an explainer on waterproof fabrics we do have a guide for that.

The use of PFOA to produce PTFE has been well and truly curtailed since 2002, with the PFOA replaced by a chemical called GenX. Neither PFOA nor GenX are things you’d necessarily want to bathe in, but the chemical industry’s habit, particularly in the states, of dumping chemicals into the nation's rivers has gone some way to creating the new legislation we’re seeing now. It’s not the PTFE itself that’s the issue, it’s the manufacture of it. So famous was the poisoning of water with PFOA by the DuPont Chemical Corporation that there's now a hollywood film, Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo and Anne Hathaway detailing the legal saga that followed.

PTFE is to all intents and purposes inert. It’s functionally insoluble, and so you can chalk it up mentally as ‘just some plastic’. This isn't to diminish the impact of plastic pollution and the potential peril of microplastics, but there's a stark difference between a functionally inert polymer and a compound being toxic. While the outdoor industry moves away from PTFE, it is upon this central tenet that Gore leans. It makes quite a compelling case on its website that while PTFE does come under the PFC/PFOA umbrella, it isn’t a PFC of environmental concern (or PFCec, to use Gore’s notation), and therefore isn’t something consumers need to concern themselves with.

There are studies in peer-reviewed journals such as Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management that conclude that fluoropolymers, of which PTFE is one, should be classed as a distinct group due to their inert nature, and therefore not subject to the same regulation. These studies, while peer reviewed, have been written by employees of, contractors to, or scientists funded by both W.L Gore, and the Chemours company, which manufacturers fluoroproducts. Despite the aspersions this may cast on the conclusions I think it is, until proven otherwise, perfectly safe to use PTFE.

It is near-ubiquitous in modern life, and outside of waterproof membranes it is found in pipe linings, the non-stick coating on your pots and pans, and even used internally in medical grafting in its expanded form, as its porous structure allows the body to grow through it. We cannot necessarily demonise PTFE simply because it has fluorine in it, any more than we can demonise table salt for containing chlorine, but as we will see shortly, the industry does seem to be moving away from it regardless. Its disposal by burning has the potential to produce harmful PFAS though, though this is disputed by Gore.

The DWR issue

The membrane of any waterproof piece of clothing is only half the story; without a durable water repellent (or DWR), the face fabric will quickly saturate, meaning there is no way for water vapour to escape and you will feel wet. It is the breakdown of DWR that many consumers think of as a jacket ‘losing its waterproofness’, though any perceived leakage is almost certainly just condensation rather than ingress; if the membrane is intact, water won’t get in, but if the face fabric is saturated, vapour won't get out.

DWR treatments have been PFC based for some time, and so this is another big shift for the industry. The problem is, sadly, that the PFC-free replacements aren’t as good; they don’t last as long, and so the jackets need reproofing earlier and more frequently. Anecdotally this is something I’ve noticed in my waterproof jacket testing, but that’s far from a scientific conclusion. Wash-in treatments like Nikwax TX-Direct are PFC free, but you’ll probably notice if you’ve ever reproofed a jacket at home that the new DWR doesn’t last as well as the factory finish.

The performance of the DWR is as integral to the performance of the product as the membrane in many ways, and Gore for now seems reluctant to shift away from a PFC based treatment, again citing that its DWR treatments are, or at least will be free from PFCs of environmental concern.

I am on board for now with the notion that PTFE is safe and inert; its use in medical procedures is a big tick in the box for me, though it's key to remember that even the medical industry isn't free from regulatory snafus. What I find harder to square away from a common sense perspective is the claim that PFC-containing DWRs are also free from environmental concern. These are surface treatments that physically wash off into the environment with use as well as directly coming into contact with our bodies, and so to my mind these should be subject to more rapid and more stringent regulation than the membranes themselves.

While the industry does seem slow to move, there are certainly more and more products being advertised with “PFC-Free DWR”. Again, this is anecdotal, but it does seem that, mirroring what is occurring with the membranes themselves, that DWR treatments will shift to be PFC-free regardless of the regulatory framework.

New membrane technology

Nature abhors a vacuum, and so does industry. The high level narrative does seem to be shifting, and the shrinking use of ePTFE does seem to be threatening Gore’s spot as top dog in the waterproof space, at least in the cycling world. For a long time and for many brands, a two-stream offering was utilised, with Gore-Tex ePTFE garments occupying the top tier, and expanded polyurethane (ePU), sitting on the ladder one rung below. Many of the myriad names that you’ll likely have glanced at in stores are ePU based membranes… Dryvent, Hyvent, eVent, and, perhaps most pertinently, Pertex.

Expanded polyurethane, or a hybrid of polyurethane and polyethylene (which I’m lumping together for now) is having a bit of a run on things at the moment, and doing the majority of the leg work to fill the receding void. While the chemical makeup may be different, and critically free from the letter F, the theory in terms of how the membrane works is identical; it's simply a membrane with a load of small holes.

Having worked in an outdoors shop for a while I always had this assumption that PU membranes were second rate. They were, after all, what brands used on their budget jackets. Given that now both my favourite road and gravel jackets both use ePU over ePTFE I think it’s fair to say that, while DWR treatments have some catching up to do, the use of ePU as a waterproof membrane is able to rival ePTFE. What’s extremely telling is that The North Face has switched to using a proprietary extruded ePU membrane in its top of the range mountaineering jackets, over ePTFE.

ePU seems to be taking up the lion's share of the market now, at least in the cycling space. Handily an ePU membrane actually has a lot higher strength to weight ratio than ePTFE, and so jackets can be made lighter even than Shakedry offerings. The POC Supreme and the new Rab Cinder Phantom are great examples of just how pared back an effective waterproof can be.

Shakedry was so well loved because it never needed a DWR coating; the waterproof membrane was at the surface, and as it was so hydrophobic water simply beaded off. Replacing this has proved more tricky, and nothing has yet cemented its place as post-ePTFE heir to the Shakedry throne. The most likely candidate for now has come in the form of a polypropylene based membrane used by Helly Hansen, courtesy of Trenchant Textiles. It’s Odin Infinity insulated shell jacket uses “Lifa Infinity Pro”, which appears to utilise a naturally hydrophobic polypropylene outer fabric as well as a polypropylene membrane, resulting in a drastic reduction in the need for DWR treatment (if at all, though I haven’t fully got to the bottom of this).

The Rapha case study

Rapha presents an interesting case study for the market as a whole. In the world of cycling it stands more or less alone now in its continued use of Gore-Tex, aside from Gorewear, and Castelli/Sportful with their use of Gore-Tex Infinium. Why not shift to other membranes? Well, I put that to Rapha's sustainability manager, Adam Gardiner.

The takeaway news is that Rapha is sticking with Gore, but will be transitioning to Gore’s new ePE (a combination of expanded polyethylene and polyurethane) membrane beginning in A/W 2024.

I also asked what Rapha's stance was regarding Gore’s use of PFCec-free, rather than truly PFC-free technologies. The answer was pretty unequivocal; the US market is so key for the brand, that the ban on PFC products (which will include PTFE and PFC-based DWR) in just a handful of states effectively constitutes a global ban, so it does appear that Gore will be in a position to provide properly PFC-free DWR coatings by the time US regulation lands in 2025.

It isn’t just a markets problem though, and to suggest it is would be to do a disservice to Rapha, which has implemented an internal mandate to be PFC free by 2025, mirroring others like Pertex in this regard.

One final point of pertinence from our chat regarded the issue of the brand's continuing stock of PTFE-based jackets in the future. With the rollout of new products, there will inevitably be a transitional period where both product streams will exist in tandem, and Gardiner is quite right to point out that the best thing to do with a PTFE-based jacket that has already been produced is to use it for as long as possible before buying something new. As we’ve covered earlier, ePTFE is inert, and so buying a new PU-based jacket to replace a PTFE one that has plenty of life left is a waste of valuable resources. I'm not going to stop using the Rapha Explore Gore-Tex Jacket for example, just because of its PTFE content.

Likewise, choosing a PTFE jacket over a PU one when you are making a purchase shouldn’t necessarily be a cause for any internal turmoil; the jacket already exists, and the tech is being phased out anyway so your purchase isn’t prolonging the life of an industry.

The sustainability of textiles is a far more wide ranging topic than I have the space to go into here sadly, and can touch on lifespans, durability, carbon footprint of production, chemical usage, water usage, recyclability, and the use of nanomaterials… Another piece, another time.

The breathability question

One additional upside to the switch, in my experience, is that the shift away from PTFE to other membranes has allowed more space for a conversation about the waterproof/breathability trade-off. In general, the more breathable a garment, the less waterproof it'll be, right the way from extreme alpine hardshells to something like a Castelli Perfetto softshell at the two extremes.

It is my suspicion that consumers saw the Gore-Tex logo, with its “Guaranteed to keep you dry” promise, and didn’t much consider the stats (I’m basing this on my own experiences to some degree here). As we will see, there are now a great array of membrane options, each falling somewhere on the spectrum. More consumer choice, and better consumer education can only be a good thing in my eyes.

One final thing to consider though is the production of ePU membranes (and any other types of polymers, in broader terms). While ePU doesn’t require PFAS, that doesn’t mean it’s suddenly some eco-friendly material. Better doesn’t necessarily mean perfect, and if a chemical company decides to launch a tonne of diisocyanates into a river, it’s still bad news for the environment.

If you’ve already got a ePTFE jacket, the best thing you can do is keep using it.

What are brands leaning towards?

It is worth noting at this point that Gore isn’t placing all its eggs in the ePTFE basket, and is itself working on developing ePU membranes. It states that its ePU membranes will be available in its products for winter 2022, so they are either out there and not yet in the cycling space, or there is going to be a slow, subtle shift from ePTFE to ePU under the same product ranges. After all, Gore-Tex Active for example is a product name, it doesn’t necessarily mean it has to remain ePTFE forever, but this is speculation for the time being.

From my point of view, in my capacity as some guy who tests waterproof jackets, I’m seeing Pertex Shield more than anything else in new jackets coming to market. It’s a PU membrane that’s been utilised by the outdoor industry for years, but now Albion, Maap, Rab, Velocio, and Pas Normal Studios have used it to great effect for on-bike protection.

To serve as a handy reference, should you wish to inform your choices in future, I’ve put together a table of prominent cycling clothing brands and the waterproofing tech they use. I’ll ensure it remains updated as and when new information becomes available.

-

Albion: Uses Pertex Shield in all of its waterproof garments, and uses a PFC-Free DWR.

-

Altura: Uses PU membranes, and it doesn’t publish that it uses PFC-free DWR treatments so it’s a relatively safe assumption that for now it does use PFCs.

-

Assos: Uses its own Schloss Tex, an ePTFE based system that utilises a PFC-based DWR.

-

Castelli: Castelli no longer makes hardshell jackets, but makes use of Gore’s Gore-Tex Infinium fabric in its softshells, which utilise what Gore calls PFCec-free DWR, or free from PFCs of environmental concern.

-

dhb: dhb uses PU membranes, and it doesn’t publish that it uses PFC-free DWR treatments so it’s a relatively safe assumption that for now it does use PFCs.

-

Endura: Endura’s Exoshell membranes are PU based, and from what I can make out it utilises PFC-free DWR treatments.

-

Maap: Maap uses Pertex (PU) and Sympatex (a polyester based membrane). Its products are bluesign approved though, and while it doesn’t mention PFC-free DWR, Bluesign doesn’t approve the use of PFC/PFAS.

-

Pas Normal Studios: PNS uses a mix of Pertex Shield (ePU) and Polartec Power Shield (bio-based ePU), both using a Bluesign approved DWR treatment, which I’m assuming means it’s PFC-free. It’s Schoeller softshell fabrics are also DWR treated, but this appears to be a PFC-based system for now.

-

Pearl Izumi: Pearl Izumi uses either non-branded PU membranes, or Polartec Neoshell (a softshell PU option), both with PFC-free DWR.

-

POC: Uses PU membranes on its jackets and is in the process of trying bio-based PU membranes on some of its insulated products. It also uses PFC-free DWR treatments, except on the current batch of Haven jackets, which will be replaced with a PFC-free system for the next round of production.

-

Rapha: Uses Gore-Tex ePTFE systems in its high end waterproof products, and proprietary membranes in its lower tier ranges like the Core range. It is assumed these are PU membranes, but it isn’t clear. It’s also not clear what DWR system it uses, but it isn't claimed to be PFC-free. Transitioning to Gore's ePE membranes in A/W2024 which will involve a PFC-free DWR too.

-

Santini: Uses Polartec Neoshell (PU) membranes, but no information on the DWR is publicly available, so as with others it’s a case of assuming PFC-based unless stated otherwise.

-

Sportful: Like Castelli, Sportful makes use of Gore’s Gore-Tex Infinium fabric in its softshells, which utilise what Gore calls PFCec-free DWR, or free from PFCs of environmental concern. It does also use PU membranes in other garments too, unlike Castelli, and appears to use a standard PFC-based DWR.

- Velocio: Velocio uses eVent (ePTFE) with a PFC DWR in some products, and Pertex (ePU) with a PFC-free DWR. Given the ban on PFCs in the US it is suspected that the brand will switch to Pertex entirely.

Conclusions

What can we conclude, if anything? Well, broadly speaking whether or not the EU ban on PFAS actually lands, it seems there's a shift away from ePTFE and PFC based DWR treatments anyway.

PTFE remains safe to wear; unless something drastic comes to light, the best thing you can do with an ePTFE based piece of clothing is to continue to use it, rather than bin it and turn it into plastic waste.

PFC-free DWR treatments are, for now, inferior, but given enough time I’ve every faith they’ll catch up; that’s just progress. Also bear in mind that any green marketing around polyurethane should be taken with a pinch of salt - It’s still a plastic that requires the use of nasty chemicals to manufacture. The most environmentally friendly course of action is to use your current waterproof for as long as possible.

Finally, this really opens the door for consumers to think more critically about the application of the products they purchase. Once PTFE was king, but as we’ve seen in testing, ePU systems can perform at the highest level. Now they’re on a more equal footing as the balance of power shifts, it's possible to pick an ePU option that suits your needs, rather than simply opting for ePTFE because its got the name brand draw.

{kiosq_button:center}