Many of the people watching The Last of Us are likely there for the zombies.

I love the zombies too, but I’m really there for the fungus.

I’ve been studying fungi since my PhD work in the 1980s, and I grow more fascinated by these amazing organisms with every passing year.

In the HBO series and the video game that inspired it, a parasitic fungus — a fictitious mutation of the very real cordyceps — jumps from insects to humans and quickly spreads around the world, rendering its victims helpless to control their thoughts and actions. Far-fetched fungal fear-mongering? It’s definitely fictional, but maybe not as preposterous as it might seem.

Fascinating fungi

From microscopic mould spores to kilometres-long mycelium under the forest floor, members of this distinct biological kingdom — neither plant nor animal — are incredible, and highly worthy of more attention.

Most of us may not think about them beyond the mushroom slices on our pizza, but fungi figure prominently in our everyday lives. Do you eat bread? Thank the fungus we call yeast. Do you enjoy beer, wine or whisky? Raise a glass to your fungal friends responsible for the fermentation that brings them to life.

Every time a round of antibiotics helps you recover from some form of infection, remember that a mould gave us the compounds that became penicillin and its many derivatives.

Fungi are incredible chemists. They make many compounds that humans cannot easily replicate in the lab. Some make compounds that can affect behaviour.

Look at lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, or “acid.” Its well-known psychedelic effects originate from a grain mould. Similarly, “magic” mushrooms are the source of psilocybin. LSD and magic mushrooms are both illegal recreational drugs but are also under study for their therapeutic value.

Fungal infections

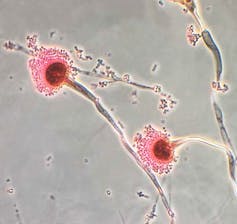

Fungi also have an aggressive side. Apart from breaking down dead plants and animals, some forms attack living creatures, including humans. Whole pharmacy shelves are stocked with remedies for athlete’s foot, yeast infections and jock itch, all of them nasty fungal infections. Even dandruff is caused by a fungus.

Yet while we can access an array of medications to cure bacterial infections such as pneumonia and strep throat, there are only four known compounds available to rid ourselves of fungal infections. Three are available in the various over-the-counter powders, sprays and ointments we use to treat common fungal infections.

The fourth and newest class, echinocandins, is reserved for hospital settings, where the consequences of fungal infections can be deadly.

My team’s research lab at McMaster is part of the university’s broader Global Nexus for Pandemics and Biological Threats, and also works with the global research organization CIFAR’s Fungal Kingdom: Threats and Opportunities program.

We are working to find ways to limit the potential harm humans face from fungal infections. We also seek to understand how we can use their abundant and as-yet barely tapped potential to make new antibiotics before we lose the waning power of penicillin and its derivatives.

Read more: Future infectious diseases: Recent history shows we can never again be complacent about pathogens

Fungi adapt and evolve

I was first attracted to fungus research as a student about to begin my PhD studies about 35 years ago. At that time, HIV-AIDS was still emerging, shutting down the immune systems of otherwise healthy people, leaving them vulnerable to opportunistic infections, including fungal infections.

I wanted to understand more about how fungi worked.

Like bacteria and viruses, fungi are always evolving and adapting, finding ways to survive under hostile conditions. We are seeing many forms of fungi adapting to live at ever-higher temperatures, including body temperature, which has long been humans’ first line of defence.

We are also seeing growing antimicrobial resistance among some causes of fungal infection, yeasts such as Candida auris and moulds such as Aspergillus, both of which can be causes of in-hospital infections.

Potential for a fungal pandemic

While The Last of Us is a strictly dramatic projection of what might happen in a deadly fungal outbreak, it is at least based, if not in reality, in logic.

Fungi are able to influence perceptions and behaviour through chemistry. Are they getting closer? You bet. Do they make zombies? Not that we know of, but the thought is darkly entertaining, and that keeps me watching.

The show does do an excellent service by reminding us that we need to adapt to stay ahead of the possibility of a fungal pandemic.

In the same way the movie All The President’s Men once inspired a generation of journalists, and The Paper Chase later channelled many eager students toward law school, I am hopeful that The Last of Us may trigger new interest in studying fungi.

The more minds we can focus on unlocking the true magic in mushrooms, the better off we’ll all be.

Gerry Wright receives funding for antifungal research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Institute for the Advanced Research and is a consultant for Kapoose Creek, a Canadian biotechnology firm.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.