For a lot of people, mention of the French Revolution conjures up images of wealthy nobles being led to the guillotine. Thanks to countless movies, books and half-remembered history lessons, many have been left with the impression the revolution was chiefly about chopping off the heads of kings, queens, dukes and other cashed-up aristocrats.

But as we approach what’s known in English as Bastille Day and in French as Quatorze Juillet – a date commemorating events of July 14 in 1789 that came to symbolise the French Revolution – it’s worth correcting this common misconception.

In fact, most people executed during the French Revolution – and particularly in its perceived bloodiest era, the nine-month “Reign of Terror” between autumn 1793 and summer 1794 – were commoners.

As historian Donald Greer wrote:

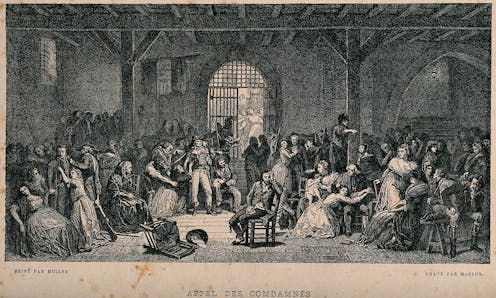

[…] more carters than princes were executed, more day labourers than dukes and marquises, three or four times as many servants than parliamentarians. The Terror swept French society from base to comb; its victims form a complete cross section of the social order of the Ancien régime.

Read more: What is Bastille Day and why is it celebrated?

The ‘national razor’

The guillotine was first put to use on April 15 1792 when a common thief called Pelletier was executed. Initially seen as an instrument of equality, however, the guillotine soon acquired a grim reputation for its list of famous victims.

Among those who died under the “national razor” (the guillotine’s nickname) were King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, many revolutionary leaders such as Georges Danton, Louis de Saint-Just and Maximilien Robespierre. Scientist Antoine Lavoisier, pre-romantic poet André Chénier, feminist Olympe de Gouges and legendary lovers Camille and Lucie Desmoulins were among its victims.

But it wasn’t just “celebrities” executed at the guillotine.

While reliable figures on the definitive number of people guillotined during the Revolution are hard to find, historians commonly project between 15,000 and 17,000 people were guillotined across France.

The bulk of it occurred during the the Reign of Terror.

When the decision was made to centralise all (legal) executions in Paris, 1,376 people were guillotined over just 47 days, between June 10 and July 27 1794. That’s about 30 a day.

The guillotine wasn’t the only method

However, the guillotine represents just one way people were executed.

Historians estimate around 20,000 men and women were summarily killed – either shot, stabbed or drowned – during the Terror across France.

They also estimate that in just under five days, 1,500 people died at the hands of Parisian mobs during the 1792 September massacres.

More broadly, around 170,000 civilians died in the civil Wars of the Vendée, while more than 700,000 French soldiers lost their lives across the 1792-1815 period.

The vast majority of these people killed were ordinary French men and women, not members of the elite.

Overall, Greer estimates 8.5% of the Terror’s victims belonged to the nobility, 6.5% to the clergy, and 85% to the Third Estate (meaning non-clerics and non-nobles). Women represented 9% of the total (but 20% and 14% of the noble and clerical categories, respectively).

Priests who had refused to take the oath of loyalty to the Revolution, émigrés who had fled the country, hoarders and profiteers who made the price of bread much dearer, or political opponents of the moment, all were deemed “enemies of the Revolution”.

Why was so much blood shed during the Reign of Terror?

The paranoia of the regime in 1793–94 was the result of various factors.

France fought at its borders against a coalition led by Europe’s monarchs to nip the revolution in the bud before it could threaten their thrones.

Meanwhile, civil war ravaged the west and south of France, conspiracy rumours circulated across the country, and political infighting intensified in Paris between opposing factions.

All these factors led to a series of laws voted up in late 1793 that enabled the expedited judgement of thousands of people suspected of counterrevolutionary beliefs.

The measures contained in the infamous “Law of Suspects” were, however, relaxed in the summer of 1794 and completely abolished in October 1795.

How the focus came to be on beheaded nobility

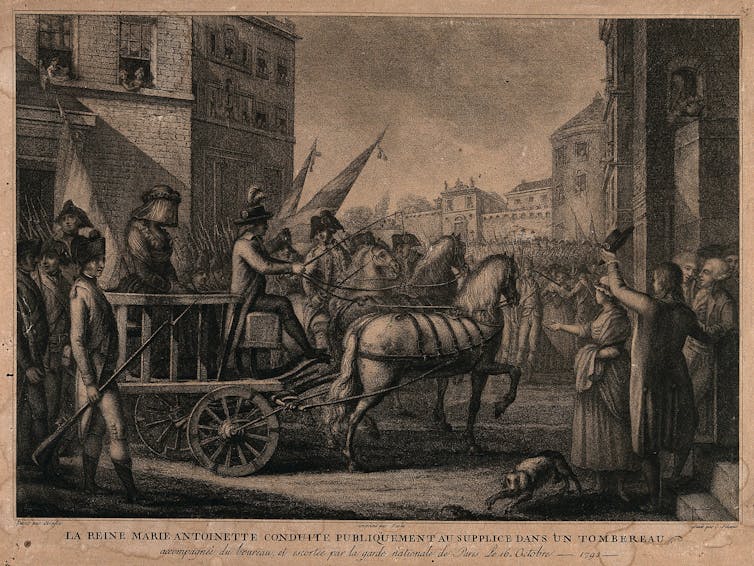

For many people, however, mention of this period of French history leads to the vision of a bloodthirsty Revolution indiscriminately sending to their death thousands of nobles.

This is largely influenced by the fate of Queen Marie-Antoinette and its many depictions in pop culture.

British counter-revolutionary propaganda in the 1790s and 1800s also helped popularise the idea that aristocrats were martyrs and the main victims of revolution executioners.

This representation was mostly forged via the abundant publication in the 19th century of memoirs and diaries of survivors and relatives of victims, usually from the social and economic elite fiercely opposed to the Revolution and its legacy.

A broader legacy

Beyond the guillotine and the Reign of Terror, the legacies of the revolution run far deeper.

The revolution abolished entrenched privileges based on birth, imposed equality before the law and opened the door to emerging forms of democratic involvement for everyday citizens.

The Revolution ushered in a time of reforms in France, across Europe and indeed across the world.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.