Several countries in the European Union are currently governed by far-right political parties. In Hungary, Fidesz under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been progressively dismantling the country’s constitutional protections of the rule of law and democratic institutions. Poland under its ruling Law and Justice party has shown equally worrying trends. Most recently, Giorgia Meloni and the Brothers of Italy party just won the Italian general elections in September 2022 and have formed a governing coalition with Matteo Salvini’s far-right Lega and Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. In Sweden, the newly elected minority government depends on support from the far-right Sweden Democrats.

While far-right parties have been present in Europe for some time, liberal democratic parties still do not know how to respond to their presence.

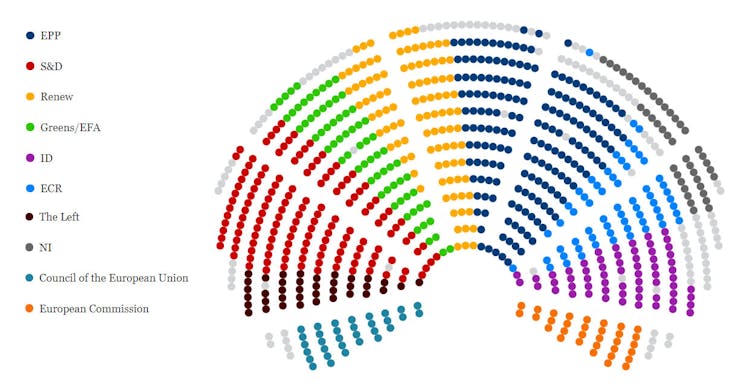

The European Parliament is a suitable place to observe the dilemmas that arise for mainstream politicians regarding the far-right. Particularly when the latter are elected democratically to office and form part of a democratic institution such as a supranational parliament. As the only directly elected body of the European Union (EU), the European Parliament hosts 705 elected members from 206 national political parties. Most of them gather in different political groups according to similar ideologies. The far right spreads widely across different political groups, underlining the degree to which they have become part of the system.

Right at the core

In 2015, Marine Le Pen and her Rassemblement National managed to create her own far-right political group and partnered with Matteo Salvini and his Lega. Today they are called the Identity and Democracy (ID) group and form the fifth-biggest political group (out of seven). Other like-minded parties include Germany’s Alternative for Germany, the Freedom Party of Austria, Belgium’s Flemish Interest, and the Danish People’s Party. Although they have been rather passive actors in the European Parliament’s committees, they have influence at the highest level. In the Conference of Presidents, each political group has one vote no matter their size. If bigger groups such as the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats do not reach a consensus, occasionally they may need far-right support to reach a majority.

The Polish Law and Justice party also lead their political group, known as the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR). It is the fourth-strongest force in the European Parliament, and also the Sweden Democrats, the Brothers of Italy, and Spain’s Vox are part of this group. In contrast, the Hungarian Fidesz was part of the biggest political group, the Christian Democrats (until 2021 known as the European People’s Party, EPP). Orbán was long shielded by powerful politicians such as former German chancellor Angela Merkel and former European Council president Donald Tusk. Fidesz left the EPP in early 2021 when internal pressure over the rule of law concerns in Hungary grew too strong to justify their membership. Today, its members do not belong to any political group in the European Parliament, depriving them of political power and visibility.

Using their political group status, far-right parties have gained not just visiblity and power, they’ve also reaped significant financial benefits. In 2017, Marine Le Pen was accused of hiring “fake assistants”, and in April of this year she and other members of her party were charged with misusing 620,000 euros of EU funds. In January, Morten Messerschmidt of the Danish People’s Party was convicted of using EU funds for political campaigning. Using European resources, many far-right political parties have thus been able to grow and expand their influence at home while simultaneously attacking the EU project.

Friends and foes

The traditional political groups in the European Parliament, including the Christian Democrats, Social Democrats, Liberals, and Greens have long had an informal agreement known as the cordon sanitaire that blocks members of the far right from obtaining key positions in Parliament.

In addition, the Social Democrats and the Greens each adopted internal policies of non-cooperation with the far right. The Social Democrats formally do not cooperate with Marine Le Pen’s Identity and Democracy Group, and while the Greens have a similar policy, it’s a bit looser – members can vote in favour of legislative proposals put forward by the far-right Identity and Democracy group if the content is deemed to be technical in nature. The Greens also leave the definition of who belongs to the far right rather open. Members can choose if they wish to boycott cooperation with certain political parties from other political groups, such as the Law and Justice or Brothers of Italy from the Europe of Conservatives and Reformists group. The cordon sanitaire is thus porous and context-dependent.

In addition, because the Christian Democrats successfully shielded Fidesz from any political pressure, it was long spared from cordon sanitaire measures. This changed in September 2018, when the European Parliament launched a formal sanctions procedure, known as Article 7 TEU, for concerns over Hungary’s democratic backsliding. Even most of the Christian Democrats voted in favour of the resolution thanks to the leadership of Judith Sargentini from the Greens, who led the negotiations at the time. After the EPP changed its internal rules to allow for the expulsion of an entire party, Fidesz chose to leave in early 2021.

These examples demonstrate the inherent complexity and ambiguity of the far right in the European Parliament. They also shed light on the circumstances under which mainstream parties – despite their convictions – can choose to support the far right.

Business as usual continues

Following the victory of the Brothers of Italy at home, not much has changed in the European Parliament. Within the Christian Democrats, there have been calls to ban Forza Italia from the EPP group should they continue to support Meloni, but this has yet to happen. Manfred Weber, head of the EPP, supported Forza Italia during the Italy’s election, and while he was strongly criticised, it’s another example of how traditional parties can directly or indirectly support and sustain far-right parties.

There have been speculations about a possible merger between Law and Justice’s ECR and Le Pen’s and Salvini’s ID group. The ECR also hosts the Brothers of Italy, while the ID is home to Italy’s Lega. In terms of numerical power, a merger would change the political game in the European Parliament – combined, they would become the third-largest force behind the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats. Yet a merger is unlikely to happen given their differing stances regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The ECR supports sanctions against Russia, most of the ID has been against them. On one issue the Brothers of Italy and the Lega do agree: both voted against a resolution in the European Parliament declaring that Hungary no longer constitutes a democracy.

An additional complication is that the electoral cycle of the European Parliament is not aligned with national elections. Even if Meloni won at the national level, it does not change the numerical representation of the Brothers of Italy in the European Parliament, and the next EU elections do not take place until May 2024. A bigger influence might be felt in the Council, where Fidesz and Law and Justice have been successfully blocking several important decisions, such as the EU budget, due to their veto rights.

The far right has become an intrinsic part of EU politics. Of even more concern is their deep political entanglement with liberal democratic political parties, which renders the whole story even more complex.

Christin Tonne is an affiliated researcher at the Albert Hirschman Centre On Democracy at the Geneva Graduate Institute (IHEID). The article is based on the research she conducted for her doctoral dissertation. She currently receives funding from the IHEID for a follow-up pilot project on democratic defenses against the far right in the EU institutions.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.