Within Texas circles, Dallas gets a bad rap. It is, some say, not as weird as Austin, as sophisticated as Houston, as beautiful as San Antonio, as historic as El Paso. A TV show with its namesake is an ode to oil, greed, and capitalism. One of the most prominent landscape features in the historically Black southern sector of the city is a literal pile of trash. As the late poet and musician, and Dallas native, David Berman wrote: “O Dallas, you shine with an evil light / How’d you turn a billion steers / Into buildings made of mirrors?” In other words, it is not a city known for its beauty.

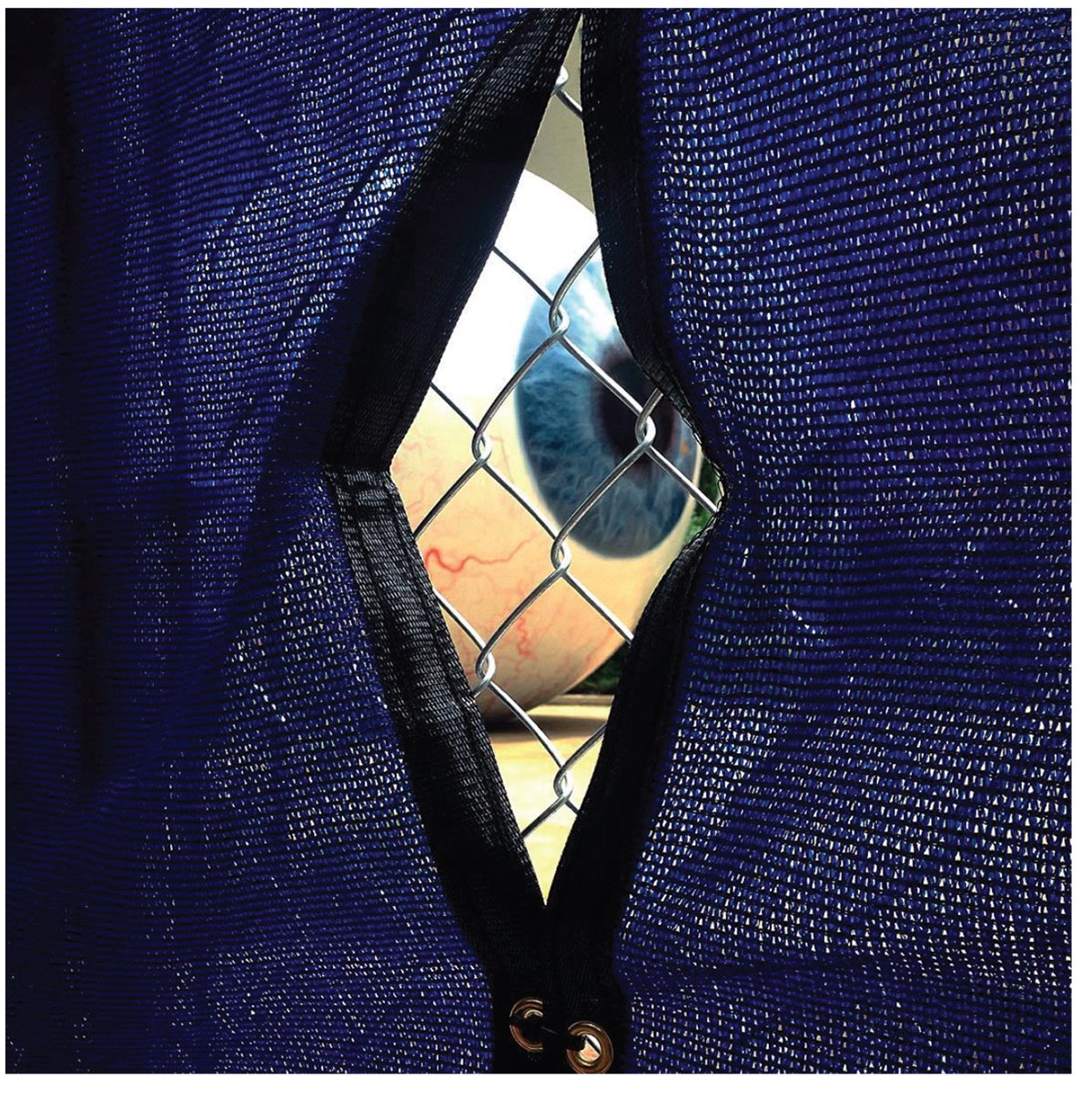

In A Pedestrian’s Recent History of Dallas, author and D Magazine music editor Zac Crain argues convincingly to the contrary. For four years, Crain spent his lunch breaks walking around downtown, getting to know every nook and cranny. “I would see somebody else’s Instagram photo and I would know exactly, from like just a crack in the sidewalk or a bit of graffiti, I’d know exactly where that was,” Crain says. At some point, he started pulling out his phone and capturing the scenes he witnessed during his perambulations.

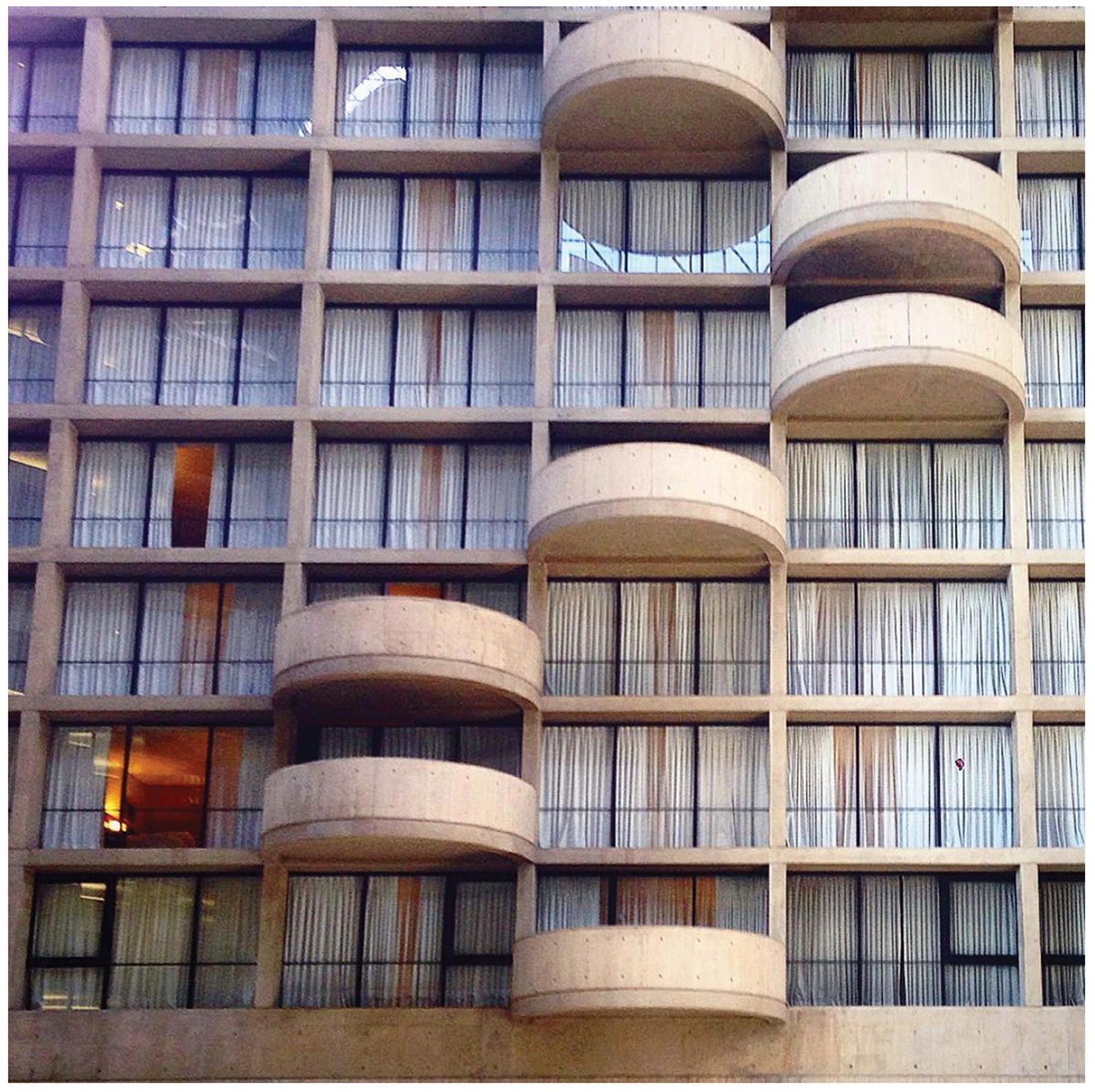

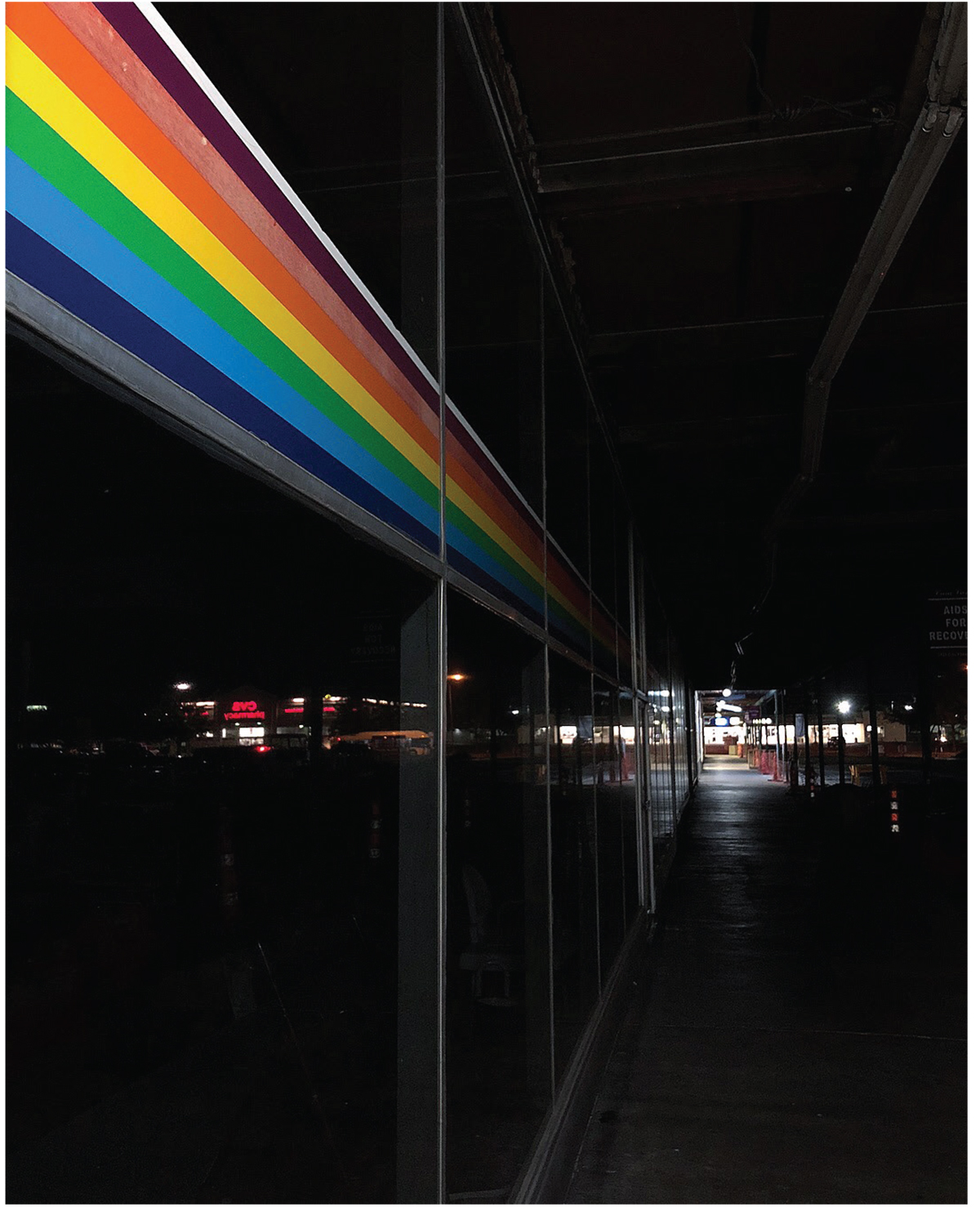

The result showcases Dallas as it is, not as it’s known: a city full of color, whimsy, and gorgeous architecture. A Pedestrian’s Recent History of Dallas is Crain’s love letter to the place he’s lived for two decades. Crain spoke to the Observer about his love for the city and what keeps him walking.

Texas Observer: Why did you start walking?

Zac Crain: I’m actually not completely sure. In the middle of January in [2016], one day I decided instead of going to lunch, I’d take a walk. I didn’t realize I’d been doing it on a regular basis until one of my coworkers pointed it out. It started around our building, which is on the edge of downtown. I started going a little bit farther and a little bit farther to just see what I could see, and at some point I started taking pictures. I’d see something that really struck me and so I’d want to remember that.

I’ve always been interested in [photography], just as a fan. But I’ve never even had a camera to speak of, other than tossaway cameras. Never took a class, never tried my hand at it much other than just knowing what I liked. I’d had a couple people on Instagram say that I should do a book, but I never really thought about it until Will [Evans, publisher of Deep Vellum] asked me.

I’ve never thought about Dallas as a walkable city. But your book kind of proves that wrong.

It is and it isn’t. The funny thing is, there’s a lot of places where it’s hard to walk because there are no sidewalks. That said, [downtown] is a lot more walkable than a lot of people think, probably more than I even thought. You can walk from one side of downtown to the other in 20 minutes. But it is a weird balance. The city has not fixed the infrastructure to make it easy. But downtown is a great place to walk. There’s a lot to see, more than you would imagine.

How did your view of the city change over the course of this project?

I love Dallas. I always have. I think it gets kind of a bad rap from a lot of people in terms of not being walkable, not being friendly, or not being especially beautiful. And there are problems, but I think there’s a lot of good architecture here and a lot of notable buildings and a lot of cool juxtapositions showing how the city has changed.

I do feel that in the four years that I was doing this pretty much every day, I probably knew downtown as well as any person in the city, just because I literally walked every single block and every alley and every sidewalk. Just being so familiar with something, you can’t help but see your love deepen.

How has the city changed since the pandemic started?

It’s strange to be in a place that you’ve walked dozens and dozens and dozens of times, and all of a sudden, something’s different. After the first year I’d [been taking pictures], I was talking to my editor. I was like, I think I’ve photographed every single thing in the city, or everything that is worth [photographing]. And he was just like, Well, just go back and take it all again. And he was sort of joking, but it’s true. Every time you go back to a spot it’s going to be different—based on the weather, based on how aware you are of something, and physically what is actually being changed or added or removed. I’ve shot the same thing a bunch. There’s places I’ve shot six or seven or 10 times, and I think all those photos are different because of what happens when you revisit something.

The city is like a living, breathing, entity.

Yeah, for sure. Now, especially in the past few years, [the change] has just revved up. It’s like being in a time lapse photo sometimes; things are just going so fast.

As much as I thought I knew my neighborhood [Lochwood], I really had no idea because I’d just been seeing it from a car, driving through it or driving somewhere else. It was weird because I didn’t even drive hardly anywhere for at least the first month of the pandemic. Finally getting in the car, it was totally different trying to drive someplace I’d walked now a bunch of times. I didn’t really understand the directions from being in a car, driving. You just see it completely differently. But I re-fell in love with my neighborhood because I saw all the beautiful parts of it.

What’s next for you?

I’d like to go on a really long walk. I’m not saying I’d like to walk the Appalachian Trail or something like that, but I’d like to go on a long walk. I’m just interested in the physicality of it, and seeing if I really could walk from one part of the city to another.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.