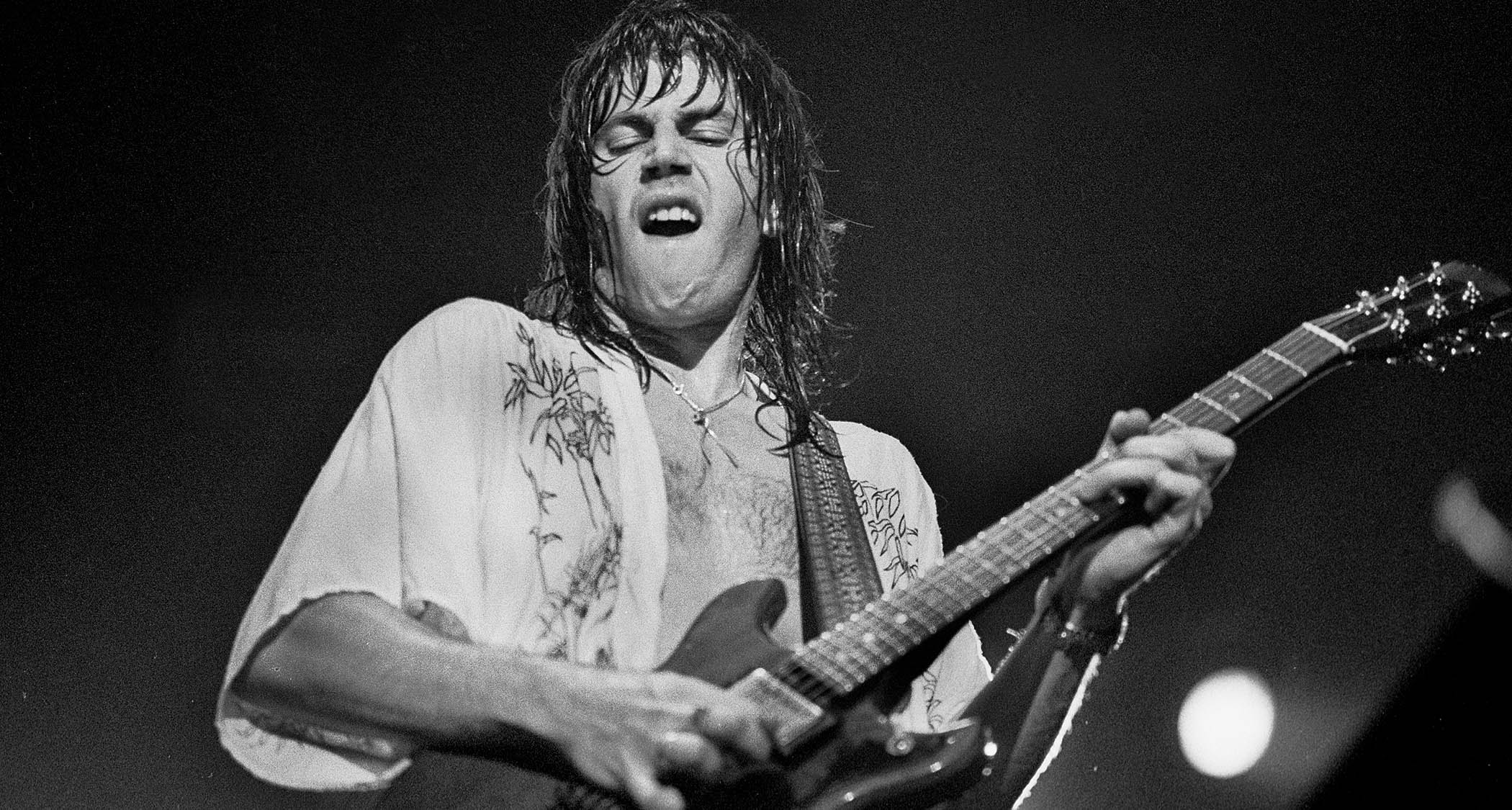

Pat Travers will be the first to tell you that he had a very good time in the 1970s. “It was an incredible decade,” he says. “We played hundreds of shows and traveled everywhere. Yeah, after the gigs, I knew how to have fun – maybe I’d smoke a little and drink a little with the other bands on the bill. But I never trashed my hotel rooms or carried on and did anything too crazy. I always knew my limit.” He laughs. “Maybe that’s why I can remember the '70s. A lot of people I came up with have no memory of what went down.”

During the second half of the ‘70s, the Canadian-born singer and guitarist was an omnipresent figure on the live show circuit. He’d cut his teeth playing the clubs of Quebec and spent a year in Ronnie Hawkins’ band, but when he decided to get serious about a record deal, he found no takers in his homeland.

“I didn’t want to go to New York or L.A., so I thought, ‘Let me try England,’” he says. In London, Travers’ rough and ready blues rock sound netted him a contract with Polydor, and his cover version of the boogie-woogie gem Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights) quickly became a fan favorite.

“I didn’t try to fit in with anything that was going on,” Travers says. “I was lucky enough to get my deal in England, but then the whole punk thing exploded, and that morphed into new wave, and then disco got huge. There was a lot of musical friction and changing tastes, and everything got too trendy in England. That’s when I decided to do my thing in the States.”

On his first three albums (1976’s Pat Travers and 1977’s Makin’ Magic and Putting It Straight), Travers performed with a trio that included British bassist Peter “Mars” Cowling and drummer Nicko McBrain (who would later go on to join Iron Maiden).

For his Stateside debut, 1979’s Heat in the Street, he expanded his lineup to feature Cowling, drummer Tommy Aldridge and guitarist Pat Thrall. He changed his billing, too; no longer were albums credited to “Pat Travers.” With Heat in the Street, it became “the Pat Travers Band.”

“Suddenly, things were firing on all cylinders,” Travers says. “It was four great players from different parts of the world, and it all came together like magic on Heat in the Street. We were a tough band. We rocked like mad, but there was some real cool stuff going on musically.”

That combustive chemistry is documented on the band’s rip-roaring ’79 release, Live! Go for what You Know, which contains the definitive rendering of Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights). Closing out the decade, the band convened to record the album Crash and Burn, which, thanks to the uproarious single Snortin’ Whiskey, resulted in Travers’ first and only Top 20 hit. Sadly, the album’s title proved prophetic, and shortly after its 1980 release, Aldridge and Thrall headed for the exits.

“It’s really unfortunate that we couldn’t keep the band going,” Travers says. “We were going faster and faster, and we were getting bigger and bigger. But before I knew it, the front wheels came off, and I went into a ditch.

“I just couldn’t control the situation. People in the band started having their own groups of friends, and once people started whispering in each other’s ears, the whole thing went downhill.

“Plus, we had management trouble, and we weren’t very smart. Everything came apart pretty quickly.” He pauses, then says, “Luckily, we’re friends now. Unfortunately, Mars passed away six years ago, but I see Pat every once in a while. I haven’t seen Tommy in a bit, but we’re friendly. We had a really good thing going for a while.”

What was the guitar scene like in London when you got there in the mid ‘70s?

“It was interesting. There was kind of a changing of the guard, but nobody knew what it was changing to. It had definitely diminished from those ’60s guys – you know, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Eric Clapton. But I did experience some guitar brilliance in the U.K. The first night I was there, I met Gary Moore.

“Actually, I first met the guys in Thin Lizzy. Scott Gorham said, ‘We’re going down to this pub. It’s a jam night, and Gary Moore is going to be there.’ I had never heard of him, but when I saw him play I was knocked out. He was amazing – so good and fast and so bluesy. That was incredibly cool.”

You were in England right as the first sparks of punk ignited.

“And I pretty much saw it right before my eyes. I had a housemate who worked for a record company, and one night he dragged me off to see this band called the 101ers. They did pretty crappy versions of Little Richard and rock ’n’ roll tunes. Well, wouldn’t you know it? Joe Strummer was in that band, and not long after he formed the Clash.”

Did you become a fan of punk?

“No, I didn’t think much of it. It was a fad. Guys would go out and grab instruments, and they thought they could make records. The cream always rises to the top, and eventually the Clash made some cool music. It was interesting seeing the change from the 101ers to the Clash. They got better clothes, and they got their teeth fixed.”

It was interesting seeing the change from the 101ers to the Clash. They got better clothes, and they got their teeth fixed

For the first three albums, you recorded and performed with a trio. Was that the format you actually wanted? I imagine you had to do extra work as the singer and sole guitarist.

“I did have to do a lot of work. And I should say that I should have had a second guitar player right away, because the music I was writing wasn’t meant for just one instrument. I was constantly looking for somebody else to play in the band. That said, playing as a trio for a time helped me to develop my performance style.”

I would also imagine you had to become a real showman.

“Oh yeah, but I was 21 and very cocky. If you run into people who knew me at the time, like Glenn Hughes, he’d say [affects British accent], “Oh, you were fucking cocky, boy!” I was a different character then. I was pretty showy because I grew up on Hendrix and Johnny Winter and Clapton.

“I wasn’t trying to be a guitar star, though. I loved playing keyboards and doing other things. I have an aptitude for the guitar, but I was never on my bed playing for 10 hours a day. That wasn’t me. Speaking of Gary Moore – he was like that. If you went to his hotel room, he’d be on the bed with Peter Green’s Les Paul, just practicing and practicing.”

One of your first songs to gain wide recognition was your cover of Boom Boom (Out Go the Lights). Had it been a staple of your live shows before you recorded it?

“No. As a matter of fact, it was one of the last songs we recorded for my first album, because I was short one song and I needed something. I remembered seeing this band in Hamilton, Ontario; it was this guy called King Biscuit Boy, but his real name was Richard Newell.

He played Little Walter material, and Boom Boom was a song Little Walter had done. I saw King Biscuit Boy when I was 13, and I never forgot him playing that song.

We recorded it in a more traditional way with piano, more of a Long John Baldry boogie-woogie kind of thing.

“[Laughs] Listen to me – ‘boogie-woogie’! But when we started playing it live, it evolved and got more rocking, and then it became a call-and-response thing. One night I was feeling pretty confident, and I knew that the audience would answer me back. It just worked.”

What was it like when you went back to the States and had to promote records? Nowadays, you can make appearances remotely. Back then, you probably had to visit every tiny little radio station and mom-and-pop record store.

“That’s how it worked, sure. It was hard, but as I was introducing myself to audiences in the States, the value in meeting people and having that one-on-one contact was inestimable. You were building relationships and becoming part of the family, in a way. And I was really pleased to discover that the people I met were on my side – they really wanted me to succeed.

I’ve always hated hotel rooms, so I was happy to be anywhere if it meant I wasn’t sitting around looking at the walls

“It was a hustle: I got up early, like six or seven in the morning, and I’d do the drive-time radio show in the morning. Then we’d hit somewhere else before soundcheck, and then I’d do some other kind of appearance before the show.

“Of course, I had a lot of energy back then. Everything was brand new, and I enjoyed it. It would wear on me now if I had to do that kind of thing, but back then it was fine. I’ve always hated hotel rooms, so I was happy to be anywhere if it meant I wasn’t sitting around looking at the walls.”

What guitars were you playing during this period?

“The guitar I took to England was a 1973 Telecaster Custom. It had one humbucker in the neck position and a Tele pickup at the bridge. It was black, and it was just like the one Keith Richards played – same black pickguard, four knobs and a maple neck. I used that guitar on the first two albums.

“I found a Gibson Melody Maker at this little mom-and-pop music shop in Sheffield, England. It just felt right, but I put a couple of humbuckers in it. I bought them at a music store in London. It was pretty basic: ‘Hey, I need some humbuckers!’ [Laughs] I didn’t do the mods myself, though. I had somebody else do the work on the guitar.”

Pat and I clicked right away. We were the same age, and his dad passed away when he was 11 or 12 – we had that in common. Pat’s appetite for music was infectious

Expanding the band really opened your music up to new possibilities. Was bringing Tommy Aldridge in your first move?

“That’s right. I had seen Tommy play with Black Oak Arkansas at the big California Jam in ’74. He did a big drum solo and was just phenomenal. Funny thing was, we didn’t play together before he joined the band. My manager made the call, and one day Tommy showed up at my hotel room.

“It was a riot; Tommy had his thick Southern accent, and my bass player Pete had this proper British accent. I was the hoser in the middle. [Laughs] But man, Tommy brought such energy to the band. The second we started playing, it was incredible. And then Pat Thrall came in.”

And as you said, you were always thinking of adding a second guitarist.

“It should have happened much sooner. Pat and I clicked right away. We were the same age, and his dad passed away when he was 11 or 12 – we had that in common. Pat’s appetite for music was infectious. He got me into reggae and Bob Marley and all sorts of stuff.

“He really wanted to know how music cooked. Plus, he was just brilliant on guitar. He played some incredible stuff, a lot of which never got recorded. I’ve got a recording somewhere with him playing an outro; it’s four minutes of insane musical freedom.”

Did it take long for you two to blend your playing styles?

“Not at all. It’s like we were of the same musical mind, but we were also different. I was more percussive and rock ’n’ roll. I came up with a sound that wasn’t necessarily standard playing; I was kind of diving around on the strings and doing this and that. Pat had a way of voicing chords that was really cool. He had a wide musical palette. He provided a lot of atmospheric and ambient sounds, things I never would have thought of. It was great.”

What kinds of guitars did Pat use to complement your sound?

“He had a Strat with no whammy bar. That’s the only one I’ve ever seen. I don’t know what happened to that guitar, but it was the coolest thing. I’d like to get one of those Strats with no whammy bar. Of course, Pat was also one of the first kids on the block to get a Floyd Rose. He just didn’t have one on that particular Strat.”

I realized pretty quickly that Ed Van Halen was a lot more than his tapping solo – a whole lot more. His rhythm, his chord choices, his voicings

We’re talking about a time when Eddie Van Halen suddenly made guitarists rethink the way they played. Did he have much impact on you?

“Not necessarily. I realized pretty quickly that Ed Van Halen was a lot more than his tapping solo – a whole lot more. His rhythm, his chord choices, his voicings – there was such melodic value to everything he played.

“Sure, he had the whole tapping and dive-bombing thing going on, but he didn’t do that in every song. It was like an effect, but it was very effective. Unfortunately, all the other guitar players in L.A. thought it was all tapping and dive bombs, and they became cartoon versions of Eddie.”

Snortin’ Whiskey is an absolutely brilliant song. I understand you had that riff for a while before you knew what to do with it.

“I did. What happened was, we were rehearsing one day and Pat Thrall was late to arrive – like, really late. I had my four-track recorder, and we were running through ideas. The day wore on, and no Pat. Finally, after about four hours, Pat burst in with his girlfriend, and they both looked a little rough.

“I asked him, ‘Dude, what in the world have you been up to?’ And he goes, ‘You know… snortin’ whiskey and drinkin’ cocaine.’ What a line, you know? I had the riff already, but those words just matched beautifully. Before you knew it, we had a great rock ’n’ roll song.”