In December 1820, when the first European explorers forged a route south from Sydney to present-day Canberra, they carried with them food, water and other essentials - and small bottles of acid.

The expedition party dispatched by governor Lachlan Macquarie and comprising Charles Throsby Smith, Joseph Wild and James Vaughan, weren't only in search of good pastures and water supply (specifically the Murrumbidgee River) to establish farms to feed the growing colony, they were also on the hunt for limestone.

Limestone was, and still is, used to make mortar (lime mixed with sand and water) so its availability was critical for future settlement to occur. And, you guessed it, one way to identify limestone is to splash it with acid. If the rock fizzes, bingo!

So, imagine the buzz around the trio's campfire on the evening of December 8, 1820, after earlier that afternoon they'd stumbled on the sought-after rock near their campsite on the northern banks of the "Yeal-am-bid-gie" (Molonglo River) near present-day Pialligo.

Smith astutely recorded the crucial discovery in his journal. "We saw several pieces of stone... which proved to be limestone... along the banks of the river... immense quantities of the same sorts," he penned.

Next morning, when Smith and Vaughan huffed and puffed up the slopes of "a very high hill downriver to the south-west" (Black Mountain) they would have noticed even more of the prized outcrops, including one above the banks of the river on the Acton flats. Two hundred years ago, even minor outcrops would have been conspicuous in what back then was primarily a treeless landscape.

Now, we've all heard of the Canberra region affectionately referred to as the "Limestone Plains" but the moniker was unlikely coined by Smith and Co, for in the first printed account (Australian Magazine, June 1821) of what is now the ACT, celebrated explorer Dr Charles Throsby (uncle of Charles Throsby Smith), referred to the occurrence of "very fine limestone... in quantities perfectly inexhaustible", but didn't specifically label the region as the "Limestone Plains".

According to Canberra-based freelance consultant and writer Mark Butz, who took a deep dive into the subject in his comprehensive essay Where has all the Limestone Gone? (Canberra Historical Journal #88, March 2022), we may never know.

"It is uncertain just when, and by whom, the area was first termed the Limestone Plains", he writes.

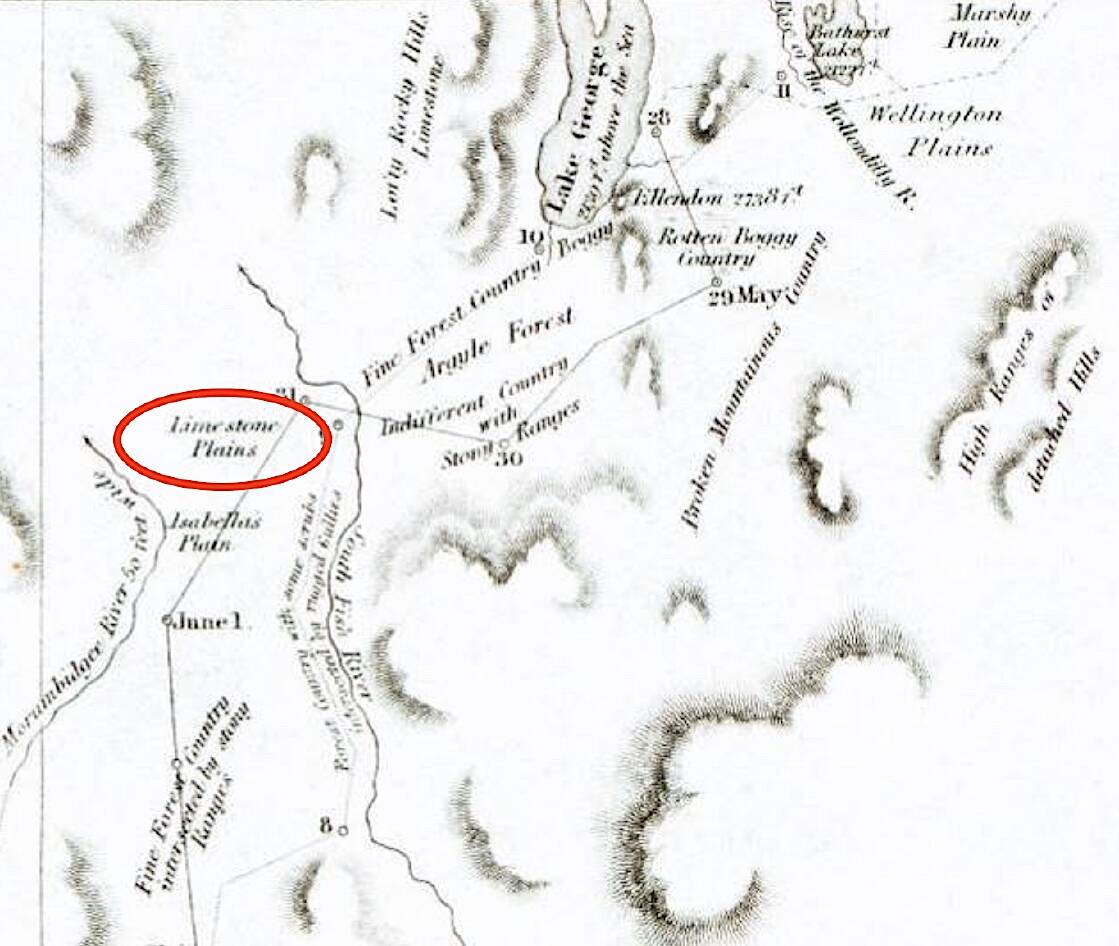

Butz reports that Queanbeyan raconteur and journalist John Gale later stated Captain Mark John Currie was responsible for the naming "as it appears on the map of the 1823 travels of Currie, Ovens and Wild to the Monaro [the 200th anniversary of which is next month] which is the earliest map to show any part of today's ACT".

However, that's not irrefutable either, for according to Butz, "Currie does not claim this in his journal, as he does for other areas". Back to square one.

Others like scholar Fred W Robinson (Canberra's First Hundred Years, WC Penfold and Co, 1924) claims Wild (presumably in consultation with Dr Charles Throsby) had already decided on the name before embarking on that 1823 expedition to the Monaro.

Regardless of who coined the phrase, it didn't take long for the name to catch on. According to Butz, "Sydney newspapers referred to the 'Limestone Plains' district from at least mid-1827", and the label is central to the earliest map of land holdings, by Surveyor Dixon in 1829, he asserts.

"The very presence of limestone was one of the determining factors in the settling of the area we now call modern-day Canberra," explains Dr Doug Finlayson, a retired earth scientist from Geoscience Australia, who for many years has taken students to examine the remnants of the Acton outcrop.

"Although the subsequent quarry and kiln that operated in Acton never reached any large scale, many of the area's first stone buildings, including Blundells Cottage and St John's Church in Reid, would likely been built using mortar from that limestone," further explains Dr Finlayson.

While there were small outcrops scattered all over central Canberra, especially in a 15-kilometre east-west band along the Molonglo River from Coppins Crossing to Jerrabomberra, due to a range of factors including mining, submergence in the lake and vandalism, there are only two locations where you still can readily eyeball traces of the fabled outcrops. Unfortunately, both have to be viewed through cyclone wire fencing.

The first is in the secure compound at Sloughing Studio (previously called Newcastle House, the former Weights & Measures Building) in Eyre Street, The Causeway, and the other is along the eastern foreshore of Acton Peninsula which has been fenced off by the National Capital Authority since March 2022 after asbestos of unknown origins was found on the ground nearby.

"The NCA is currently in the early stages of scoping to find a more permanent long-term solution for the area," explains a spokesperson for the authority, who also advises "at this stage we are not able to give further advice on the anticipated timeline for this work".

Given these geological treasures provide a tangible link to the founding of our city and form an alluring part of our region's identity, let's hope the only (usually) publicly accessible outcrop left in central Canberra can be cleaned up and made safe to access again.

Don't miss: Next week's column for part two in this series on the Limestone Plains - The hidden caves of central Canberra.

The rocks that helped lay Canberra's foundation

Life's a beach: The limestone around Canberra is literally older than the hills, having been laid down as deep sea sediment some 420 million years ago during the Silurian Period when our region was at tropical latitudes and warm, shallow seas were conducive to the formation of coral reefs and limestones around island arc volcanoes.

Capital capers: In 1911, maps on the area's geology were included as part of the information pack sent to design competitors for the national capital. The maps, prepared by government geologist Edward Pittman, described the limestone outcrops in central Canberra as "numerous in the city area and the surrounding territory". However, according to historian Mark Butz, "the building of Canberra required a lot more concrete than could be supplied from local limestone, and in 1915 the Commonwealth compulsorily acquired the limestone deposit at Mt Fairy" near Bungendore to enable either cement manufacture or quarrying of marble. Supply of lime for mortar in Canberra was also taken up by a new quarry and kiln at White Rocks south of Queanbeyan and by an older kiln at nearby Jumping Creek.

Acton legacy: Black marble from the Acton limestone quarry located near present-day Lawson Crescent was used in the marble floor in the foyer of the Institute of Anatomy building (opened 1931), now home to the National Film and Sound Archive.

Divine patch: An outcrop of limestone just south-west of St John's Church in Reid was chipped away by so many fossil hunters that it had virtually vanished by 1940. Meanwhile, a former limestone quarry 13km north of the city was subsequently filled with rubbish and now, somewhat ironically, forms part of the suburb named after Dr Charles Throsby, the person recognised as the first to describe the importance of limestone in the area.

It's all in a name? European settlers initially referred to the Yealambidgie River as the Limestone River before it was renamed the Molonglo.

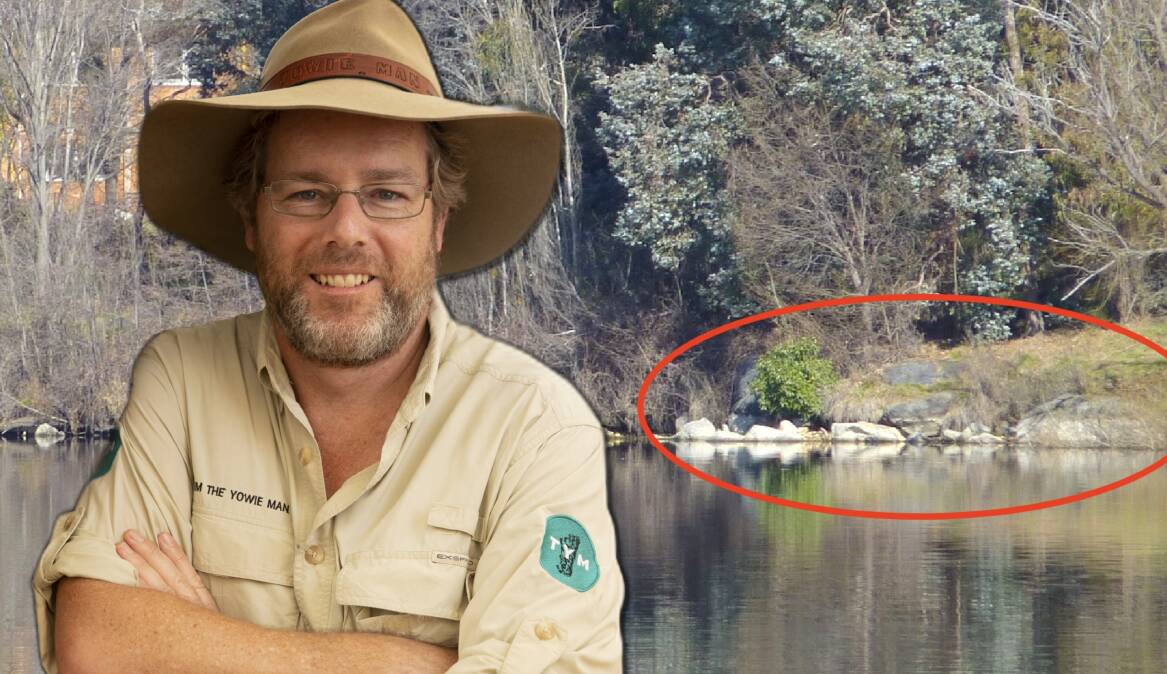

WHERE IN CANBERRA?

Rating: Medium

Clue: Beyond the limestone

How to enter: Email your guess along with your name and address to tym@iinet.net.au. The first correct email sent after 10am, Saturday May 27 wins a double pass to Dendy, the Home of Quality Cinema.

Last week: Congratulations to Jeff Day of Greenway who was first to identify last week's photo as the view over the Murrumbidgee Valley from the top of the 728-metre-high Mt Urambi in the Urambi Hills Nature Reserve on the southern edge of Kambah. The Urambi Hill Trig Point is just out of view, a couple of metres behind the chairs. Jeff, a first-time winner, just beat Graham Wylie and Jeremy Finch of Queanbeyan to the prize. Despite being 75 years of age, Jeff "still walks [2.3km return] up the hill several times a week". Impressive.

Like several other readers, Jeff is not impressed with the plastic chairs that recently appeared at the summit. "Whoever the clowns were who carried the chairs up, they should be made to take them back down again as they are creating an eyesore and unnecessary clutter in what is a beautiful location".

Heritage up in smoke

Like many, I was saddened to see the Commercial Hotel in Yass destroyed by fire earlier this week.

In its heyday, the Commercial was widely regarded as one of the best hotels in the district and hosted at least two governors-general (Lord Belmore in 1868 and 1871) and Lord Carrington (1888). Celebrated aviator Charles Kingsford Smith also bunked down in the pub and according to a spokesperson from the Yass & District Historical Society, the veranda (recently removed due to safety concerns) "hosted a wide range of gatherings from would-be politicians appealing to the locals gathered below, and the first official send-off of local men who enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in August 1914".

Regular correspondent and local wine industry luminary Ken Helm of Murrumbateman describes the loss of the historic watering hole as a "tragedy".

"My parents stayed there on their honeymoon during a heatwave in 1939 and it was so hot they pulled the mattress out onto the front veranda," reveals Ken. "They woke in the morning to find many other guests had done the same."

CONTACT TIM: Email: tym@iinet.net.au or Twitter: @TimYowie or write c/- The Canberra Times, GPO Box 606, Civic, ACT, 2601

We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on The Canberra Times website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. See our moderation policy here.