It ended ugly, with a longtime North Carolina assistant coach chasing a controversial official into the back hallways of the Hoosier Dome in search of a confrontation. There was enough shoving and shouting to make headlines in the newspapers the next day, but stadium security intervened and a major physical altercation was narrowly averted.

Also narrowly averted that night in Indianapolis: the biggest Duke–North Carolina game of all, for the national championship in 1991.

Instead, that distinction now belongs to the Final Four semifinal matchup of the Blue Devils and Tar Heels Saturday night in New Orleans. It is an epic story line beyond the rivalry itself: Duke program patriarch Mike Krzyzewski trying to win a national championship on his way into retirement, Carolina trying to end his career before then and win its own title under first-year coach Hubert Davis.

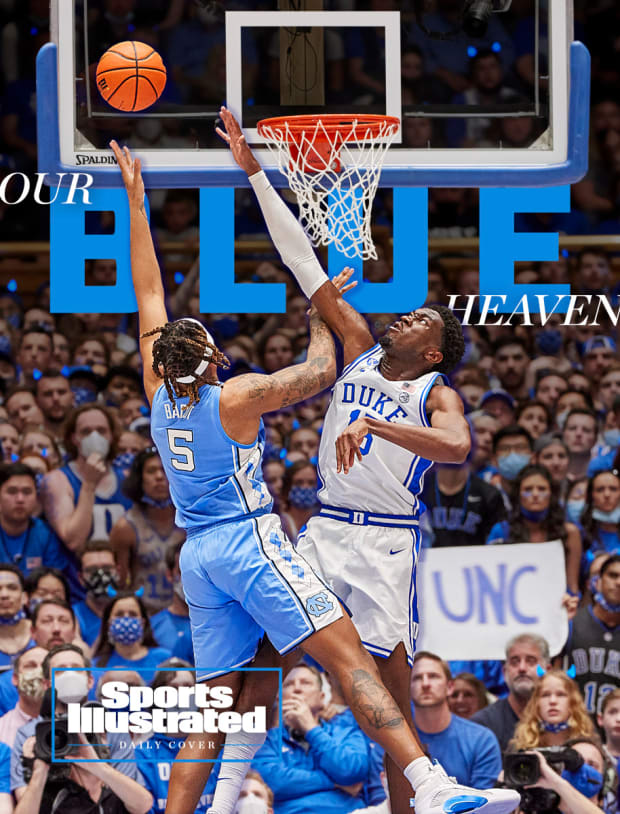

Photo Illustration by SI Art; Chris Keane/Sports Illustrated

Somehow, these two bluebloods have never met in the NCAA tournament before now. They’ve combined to play 334 tourney games, none of them against each other. “Very surprising,” says Davis.

As spellbinding as the Atlantic Coast Conference clashes have been between Duke and Carolina over the decades, this game offers next-level stakes. One has never ended the other’s season when there were legitimate national title hopes on the line. Even beyond the Coach K subplot to end all subplots, this is huge.

Still, it could have been even bigger 31 years ago, the only other time the Devils and Heels both made the Final Four. North Carolina was playing Kansas, Duke taking on UNLV—each powerhouse program was 40 minutes away from a Monday night showdown for the whole damn thing. “We would have been playing for everything,” Mike Krzyzewski says. “That would have been something.”

But only one would advance, and it wasn’t the one most were expecting.

This was one of the most momentous nights in Final Four history: a massive upset of an undefeated juggernaut; a shocking ejection of a legendary coach; and the ultimate Tobacco Roadshow ironically undone by a former-and-future participant in the Duke-Carolina rivalry. It was the first Final Four I ever attended, and I’ve covered them all since then. Across those 30 Final Fours, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a wilder Saturday night.

The conventional wisdom heading into those semifinals was that a Duke-Carolina title game was unlikely. Undefeated, reigning champion UNLV was expected to dispatch Duke (as it had the previous year in the title game), and North Carolina was predicted to defeat Kansas.

“Everyone thought we would beat Kansas,” says the Carolina point guard at the time, King Rice, now the head coach at Monmouth. “Nobody thought Duke would beat Vegas.”

Davis, a junior on that 1990–91 North Carolina team, insists that Dean Smith never brought up the possibility of playing Duke for the national title. “It was not even talked about with coach Smith,” Davis says. “It would be a waste of time to talk about a possible matchup. We were focused on Kansas.”

Rice tells a slightly different story. As the team’s senior floor leader, he says Smith confided a bit more in him. “Coach Smith wanted Vegas,” Rice recalls. “Because they had been blowing everyone out and hadn’t played many close games. He thought if you got them in a close game, maybe you could beat them.”

Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated

Duke, for its part, definitely wasn’t looking ahead. Not with a UNLV team in its way that had destroyed the Blue Devils by 30 points the year before in the title game. From the moment the bracket was released on Selection Sunday, Duke’s eyes were locked on that potential semifinal rematch.

This was a much improved Blue Devils team from 1990, one that believed it could compete with the Runnin’ Rebels if given a second shot at them. Krzyzewski added freshman Grant Hill, guard Bobby Hurley had improved from his freshman season, and Christian Laettner was the junior centerpiece.

Duke proved its mettle in the ACC, winning the league by sweeping Carolina in the regular season. But the Tar Heels blew out the Blue Devils in the ACC tourney, winning by 22 and legitimizing themselves as national title contenders.

Duke entered the Big Dance as the No. 2 seed in the Midwest Region, Carolina as the No. 1 seed in the East. The Devils rolled to four straight double-digit wins to reach Indy, easily dispatching No. 4 seed St. John’s in the regional final. The Heels had three authoritative wins before squeezing past longshot No. 10 seed Temple by three in the Elite Eight.

For those who weren’t predisposed to daydream about a Duke-Carolina title game, the semifinals offered immense allure of their own. Not only was there the Duke-UNLV rematch, but Smith was taking on his former pupil and assistant coach, Roy Williams, who had left his side in Chapel Hill three years earlier to take over at Kansas.

That was awkward for both men, not to mention the Carolina upperclassmen who had been recruited and coached by Williams. Armed with a superior knowledge of his opponent’s personnel, Williams had the Jayhawks ready.

From the early stages of the game, the Heels were not quite in sync. Rice said that he and the other two seniors, forwards Rick Fox and Pete Chilcutt, had developed a successful synergy throughout the season: When one had a bad game, the other two usually played well and picked up the slack. This time, all three of them struggled simultaneously: Rice was 1-for-6 from the field, Chilcutt was 2-for-8 and Fox was a ghastly 5-for-22.

Rice, a pass-first point guard, took a couple early shots, saying he felt overly motivated to make a name for himself on this big stage. He said Smith told him at the first TV timeout, “That’s enough.” After that, he resumed doing what he usually did, setting the table for his teammates—particularly Fox.

“I kept going to him, because Rick got us there,” Rice says. “He was my best friend and a great player. He just couldn’t hit a shot. People talked about Alonzo Jamison’s defense? Stop it. Rick had an off night. Then it became a terrible night.”

Terrible transpired in the final minute. Smith had been given a technical foul in the first half by Pete Pavia, a Big East official with a history of tossing big names out of games: Billy Tubbs of Oklahoma the week before in the NIT, and Georgetown’s John Thompson, Connecticut’s Jim Calhoun and Temple’s John Chaney within the previous two seasons.

With 35 seconds to go, after Fox fouled out, Smith said he repeatedly asked Pavia how much time he had to make a substitution. The third time he asked, Pavia hit him with a second technical. One of the towering figures of the sport was ejected from the Final Four—just his third ejection in 30 years of coaching—while playing against a dear friend.

“We all knew Coach Smith doesn’t cuss,” Rice says. “So it wasn’t that. And he’d never get thrown out on purpose and upstage any coach, much less Coach Williams.”

Smith’s exit was not bellicose, but it was elaborate. He stopped to congratulate Williams and apologize for sullying the end of Kansas’s 79–73 triumph, then shook hands with every Jayhawk before leaving the floor. Fans were outraged, and so were the Heels themselves.

Which brings us back to the postgame confrontation in the Hoosier Dome hallway. Smith’s longtime assistant, Bill Guthridge, was so enraged that he chased Pavia off the floor, yelling, “That’s bush! That’s bush! Where did you learn to officiate?”

This was a shocking display from Guthridge, whom Rice calls “the nicest man ever.”

“But that night, whoa, he went after [Pavia],” Rice says. “I’m glad he didn’t get to him. That would have been bad.”

Williams was distraught over the ejection for Smith and angry on behalf of his own players. This wasn’t an overly talented Kansas team, and the Jayhawks had just beaten a Carolina roster that had many future multiyear NBA players on it. The program’s comeback from major NCAA sanctions for violations under Larry Brown was reaching a high point, and it was overshadowed.

“I was mad,” Williams says. “Pete was an all right official, but that was a bad move. I was so ticked off because I knew how the press conference was going to go. My dadgum Kansas team played their butt off that day, and all the questions were about Coach Smith being ejected.”

As a 26-year-old reporter for the (Louisville) Courier-Journal, I had been assigned the Carolina-Kansas game—the undercard game, given the wattage of Duke–UNLV, but still a tremendous assignment at a young age. After Smith was ejected, I giddily believed I had the biggest story of the night fall into my lap.

After his press conference, Williams went out to watch his old Tobacco Road rival take on a 34–0 powerhouse—and like Smith, he was quietly hoping the Runnin’ Rebels would win. He thought that was the better matchup for his team.

“I was mad at Kansas fans for cheering for Vegas,” Williams says. “We loved people pressing us, and that’s what Vegas did. We beat them the year before, when they won it all. I wanted to play Vegas.”

Earlier, Duke players were watching the end of Carolina–Kansas on a TV in the locker room. That’s when Krzyzewski came charging into the room to issue one more challenge to his team: “Hey, it’s not all right to lose because they lost.”

That’s how all-encompassing the rivalry can be. “You’re always measuring yourself against Carolina,” Hurley says. “It’s in your face all the time. Coach K was trying to say that we couldn’t relax now just because Carolina couldn’t advance farther than us.”

There was no need to worry about that. Fiercely motivated to stand up to the opponent that had punked them the year before, the Devils raced to a 13–5 lead. It was immediately clear that this game would be different.

Early in the second half, Duke guard Billy McCaffrey ran under UNLV’s Anderson Hunt on a layup. That sparked some indignation from the Rebels, and Stacey Augmon retaliated the next time down the floor by hammering McCaffrey with an elbow while fighting through a screen. Augmon was whistled for an intentional foul.

Later, Hurley aggressively wrapped up UNLV’s Greg Anthony to stop a breakaway layup and tempers flared anew. In the aftermath of the play, UNLV star Larry Johnson hit Hill in the chest and was whistled for a technical.

“I just had a chip on my shoulder,” Hurley says. “I’m a Jersey guy. A lot of teams had backed down from Vegas. We were not going to back down from anybody.”

As Dean Smith had expected, the longer the game stayed close, the more stress was exerted on UNLV. Duke, having been through the ACC wars, was largely unfazed. When Anthony fouled out, Vegas was without a reliable ball handler. And when Laettner was fouled following an offensive rebound with 12.7 seconds left in a tie game, everything hung in the balance.

It was precisely then that I rushed back into the arena from the media workroom, having finished my Carolina-Kansas story. I looked at the scoreboard and was shocked—I no longer had the biggest story of the night.

I watched Laettner calmly swish two free throws to make it 79–77. The entire Hoosier Dome crowd was on its feet and holding its breath for the final UNLV possession. It turned out to be a mess without Anthony running the point.

Johnson tentatively dribbled upcourt, unsure what to do, finally passing to Hunt for a rushed and contested three that missed badly. One of the biggest upsets in Final Four history was in the books.

“That was probably the best game I played in,” Hurley says. “The one the next year [the fabled 104–103 win over Kentucky in the regional final] was more dramatic, but this was probably a better game against a better team. We had to be pretty much perfect to beat them, and we nearly were.”

John Wooden, greatest coach of them all, winner of 10 NCAA titles, was in the stands for that game. The octogenarian had come to appraise a UNLV team that had been compared to some of his best at UCLA, trying to become the first repeat champion since his Bruins won seven straight from 1967 to ’73. When it ended and UNLV had been beaten, he delivered an ice-cold exit line to Mike Lupica of the New York Daily News on his way to the exit: “A lot of teams have won one in a row.”

The postgame scene back at the Duke hotel was “insane,” Hurley recalls. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like that.” The players were engulfed by inebriated fans and family members and hangers on. While some of them stayed in the lobby to soak it up, Hurley escaped to his mom’s room.

He was too amped to sleep, so he played cards with family. But he wanted no part of a premature celebration after playing so poorly the previous year in the championship game.

“I was totally locked in,” he says. “I knew the Kansas game was going to be hard.”

While Duke advanced, North Carolina went home. The Heels left early that Sunday, devastated by their defeat and appalled that the Blue Devils were still playing.

Again not taking any chances with complacency, Krzyzewski jumped on his players during the Sunday practice between games. “He thought some guys were being too casual,” Hurley says. “He wanted to bring the whole group down to Earth. He told us that beating Vegas means nothing if we don’t seal the deal on Monday.”

They sealed the deal. Kansas came out nervous—Williams can laugh now at his team getting an over-and-back call on the opening tip, a turnover just two seconds into the game—and couldn’t keep pace offensively. Duke never trailed on the way to its first national title.

In Chapel Hill, King Rice flipped on the TV long enough to see Duke in the lead in the second half and flipped it back off. “That was when their program started feeling like they were the program,” he says.

In Indy, the Blue Devils’ breakthrough moment had finally arrived, and a repeat title would follow in ’92 with an all-time great team. “It was indescribable,” Hurley says. “You’re standing there, and you’ve done it. Forty-eight hours ago you’re this massive underdog, and then you’re a champion. It changes you in a lot of ways. It’s amazing how it transforms you.”

Transformation awaits a new team and a new generation of players Monday night. We know this much: Either Duke or North Carolina will be in it, and the other one will be bitterly jealous.

Bill Streicher/USA TODAY Sports

The one Tar Heel who played well in the 1991 Final Four loss that unsprung Tobacco Road armageddon was none other than Hubert Davis. The junior scored 25 points, trying to will Carolina into the title game.

A Heels fan since his youth, when his uncle Walter was a UNC star in the 1970s, he’d missed the first half of Dean Smith’s first title victory over Georgetown in ’82. The reason: His parents made him attend a Boy Scout meeting. When Smith won his second and last title in ’93, Davis was an NBA rookie with the Knicks. He watched the game on TV from a hotel in Atlanta.

The emotions watching that win over Michigan’s Fab Five conflicted—happiness for his former teammates, but the emptiness of 1991 was present as well. “I was sad because that had always been my hope and dream, to cut down the nets in a Carolina uniform, and I didn’t get to do that,” Davis says.

He won’t be in uniform this weekend, but he will certainly be involved in deciding the outcome. So will Krzyzewski, trying for the ultimate mike drop with a sixth title and a ride into the sunset.

This week, both coaches are trying to shrink the focus to simply the competition and trying to win a national championship. It’s impossible, they say, to add extra motivation by playing your biggest rival. But the consequences of both victory and defeat are hard to understate.

This paragraph came from a March 1995 Sports Illustrated story by Alexander Wolff on the Duke-Carolina rivalry:

“The two schools have never met in an NCAA championship game, although it’s bound to happen one of these days. Smith is on record as saying he wouldn’t mind such a matchup. But Krzyzewski—could he possibly do anything else?—disagrees. He recounts how once, after a North Carolina victory over Duke, a gang of students followed his eldest daughter, Debbie, through the halls of her junior high school in Durham, bumping and taunting her to tears. Even teachers joined in, writing ‘Go Heels!’ in the margins of papers before returning them to her. ‘I can live with losing to any school,’ Krzyzewski says. ‘But what would happen in this area peoplewise if one of us beat the other in the championship game I wouldn't wish on anybody, it would be so horrible.’”

This isn’t quite the championship game, but it’s as close as it can get. So I asked Coach K this week if he still feels that way.

“I was a lot younger, so I’ve probably learned from my mistakes in that regard,” he says. “I think the area, no matter what, will still go on. The fan bases are different, with the proximity. It evokes things that can’t be done in other areas. So go at it. I’m not going to be part of it.”

In an ideal world, the two intertwined fan bases in North Carolina’s Research Triangle region will treat this as a celebration of mutual excellence. In the real world, the winners will never let the losers hear the end of it. That’s Duke-Carolina, and that’s what happens when the long-fantasized Final Four showdown arrives—three decades late, but here at last.