So your doctor removed a mole from your skin and now says it’s cancerous. What happens next?

Firstly, you’re not alone! Two in three Australians will have a skin cancer in their lifetime, nearly all of them basal cell carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, or melanomas.

If you have a “mole” – brown, round spots than can be flat or raised – removed and diagnosed as cancer, though, you’re probably talking about a melanoma. The other types are more likely to be pink, scaly lumps or sores that sometimes bleed. (See our piece about these more common types – basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas – here).

Melanoma is the rarest of the main skin cancers, and also the most likely to spread around the body, which is called metastasis. How likely this is mostly depends on how deeply into the skin the melanoma has spread by the time it’s diagnosed. This is why earlier, and hopefully thinner, detection is so important to your outcome.

Read more: Why does Australia have so much skin cancer? (Hint: it's not because of an ozone hole)

In 2021, nearly 40,000 melanomas were excised in Australia. About 23,000 are very thin “in situ” melanomas, where the cancer is confined to the very top layer of the skin and can spread locally but not around the body yet. The others are invasive melanomas, meaning they have grown into the deeper parts of the skin. “Invasive” sounds scary, but most actually only have very shallow invasion and an excellent prognosis.

So it’s a melanoma, what’s next?

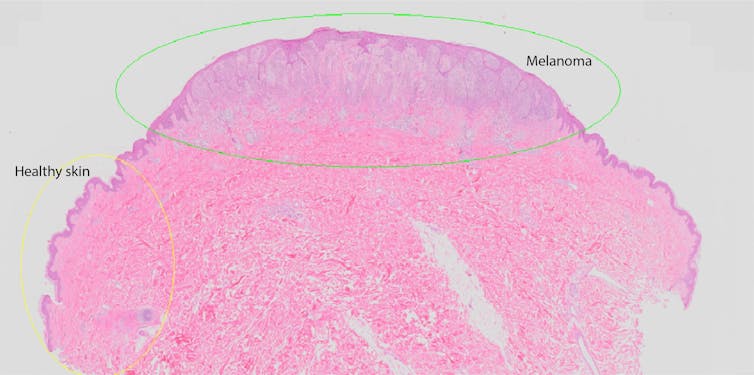

After the initial excision of the melanoma, it’s sent to a pathologist to be examined under a microscope. They will generate a report describing the melanoma in detail to help your doctor know what to do next.

The most important detail is the thickness of the melanoma from the skin surface to its deepest edge. In situ melanomas are so thin they have no official measurement, and invasive melanomas are measured in millimetres. Over 1mm thick is where your doctor will start to be much more concerned about the risk of spread.

The report will also tell your doctor whether the melanoma was ulcerated, invaded by immune cells, or near a blood vessel or nerve.

If your melanoma is less than 1mm thick, the first step is a wide local excision. This is removing more skin around the original melanoma site. How much is removed depends on how thick the melanoma was and what type it was.

In-situ melanomas generally need an extra 5mm of skin removed on each side of the original wound. For invasive melanomas under 1mm thick, it’s 1cm extra clearance.

The pathologist will check the re-excision under a microscope to check the edges of the melanoma are far enough away from the edge of the cut. If it’s not, more skin will need to be removed and checked again.

For most people with in-situ melanoma, that’s the end of their cancer treatment, although your doctor may want to set you up with ongoing regular skin checks. Melanomas less than 1mm thick (also called stage 1 melanomas) are also very unlikely to have spread and have a five year survival rate of 99%.

Read more: Health Check: do I need a skin cancer check?

What are the chances it’s spread?

The most important risk factor for spreading is again the tumour thickness. Melanomas more than 4mm thick are of the most concern. If the melanoma was ulcerated, or was touching a blood vessel or nerve, the risk of spread is also higher.

If your melanoma is more than 1mm thick, your doctor will discuss with you the possibility of a sentinel lymph node biopsy and refer you to a specialist surgeon.

Read more: Spot the difference: harmless mole or potential skin cancer?

Your lymph nodes are part of your immune system, and are clustered in basins at your armpits, groin and neck. Melanoma cells that spread are carried there first, and the one that receives it is called the draining lymph node.

To find the draining lymph node, you will have an injection containing a tiny dose of radioactive tracer dye into the melanoma site, so it will travel to the lymph node and be detectable with a nuclear medicine camera. This allows a surgeon to plan where to operate.

Then, while you’re under a general anaesthetic, a blue dye is injected into the site of your melanoma to stain the draining lymph node, so the surgeon can remove the correct node and leave all the others. They will also perform the wide local excision of the original melanoma site at this point – 1-2cm extra clearance, depending on the original tumour thickness.

If the node has no melanoma cells, you won’t need any further treatment besides a six-monthly or yearly follow-up physical exam. This checks for unexpected recurrences by checking for swelling at your lymph nodes and any concerning symptoms such as unexplained weight loss, pain or fatigue. This check will also look for new primary melanomas on the skin.

Read more: Sun damage and cancer: how UV radiation affects our skin

If there is a positive lymph node, you might be invited to participate in clinical trials with immunotherapy drugs. There will also be further investigations to check whether the melanoma has spread further, and if so, where.

These scale up from ultrasound checks of the rest of the lymph nodes, to PET/CT scans of the rest of the body, or even MRI scans if there are signs of spread to the brain. If there are metastases, you’ll work with an oncologist to discuss surgical removal and what drug treatment you might need.

Having one melanoma means you are at risk of having more in the future, so the final part of your treatment program will be regular skin checks with your doctor. Your GP might do these themselves, or refer you to a dermatologist or another GP who has specialised in skin cancer.

You should also learn to check your own skin between visits, so you can bring a new or changing lesion to your doctor’s attention early.

Katie Lee receives funding from the NHMRC and The University of Queensland.

H. Peter Soyer is a shareholder of MoleMap NZ Limited and e-derm consult GmbH, and undertakes regular teledermatological reporting for both companies. He is a Medical Consultant for Canfield Scientific Inc, MoleMap Australia Pty Ltd, Blaze Bioscience Inc, and a Medical Advisor for First Derm. He holds an NHMRC MRFF Next Generation Clinical Researchers Program Practitioner Fellowship (APP1137127) and several other NHMRC and MRFF grants. He is a Board Member of Melanoma and Skin Cancer Trials Limited and the Queensland Skin and Cancer Foundation. He is employed by The University of Queensland and works as Visiting Medical Officer at Metro South HHS.

Erin McMeniman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.